This article is part of a series of articles authored by young, aspiring China scholars under the Future CHOICE initiative.

On April 3, Hungarians went to the polls to vote in one of the country’s most eagerly watched parliamentary elections. As far as the results, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s victory was no big surprise. However, the lackluster performance of a six-party opposition was a shock.

The combined opposition underperformed the previous expectations about a tight race, gaining only 35 percent of the vote. As such, Orbán is set to begin his fifth term with his Fidesz party taking two-thirds of parliamentary seats, cementing a supermajority.

While foreign affairs are generally left out in Hungarian public debates, there was a moment last year when relations with China almost took center stage. Although the war next door in Ukraine obviously altered the core messaging of the campaigns and China disappeared from the domestic discourse, the issue’s emergence signals a closer public review of the relationship.

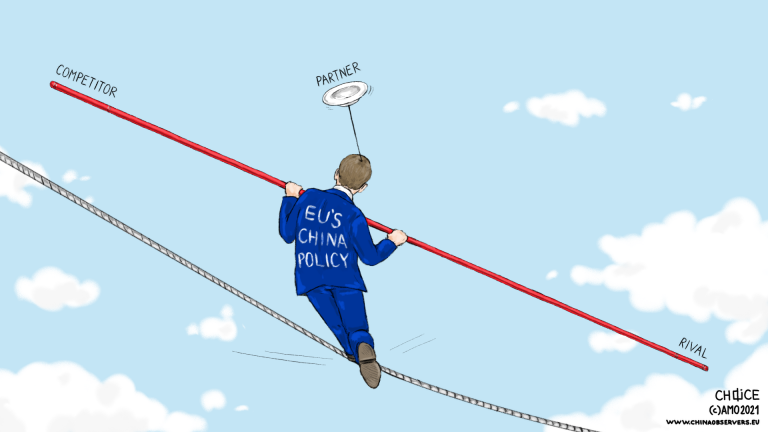

Shrinking Room on a Tightrope

The war in Ukraine is becoming a turning point for Europe.

Countries maintaining strong relations with Russia are under scrutiny, with many urgently changing tack in their foreign policies. Yet, the current changes may not only affect relations with Russia. Indeed, there are growing calls to re-assess the exposure to and dependence on other autocratic regimes, most prominently China.

The past 12 years have seen Hungary deepen ties with authoritarian regimes, each of whom is beginning to look like costly partners to maintain.

Yet, Hungary seems to be bucking the EU trend. Prime Minister Orbán voted for the EU sanctions against Russia but drew a red line at rejecting the transport of weapons through Hungarian territory and emphasized his opposition to extending the EU’s restrictive measures to the energy sector.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy singled out Orbán during the last EU Summit for not taking a clear stance and providing stronger support for his country, which Orbán rejected.

To be sure, Hungary-Ukraine relations have been complicated for some time now. However, Orbán even appears to be losing his erstwhile defenders. While the Hungarian prime minister has attempted to carefully balance between satisfying Hungary’s Transatlantic allies without alienating Russia, his approach drew criticism from Hungary’s staunch regional ally, Poland. This was followed by both the Czech Republic and Poland canceling their participation in the planned defense ministers’ meeting between the Visegrád 4 nations over Budapest’s policy.

The increasing isolation has implications for Orbán’s ability to continue to use Hungary’s ties to authoritarian regimes as leverage inside the EU. It is obvious that, in light of Moscow’s aggression, Hungary has to re-evaluate its Russia policy. The extent to which Orbán will actually shift stances remains to be seen, however.

Little Prospect of a Pivot

Under the current circumstances, it is unlikely that Orbán would change tack with Beijing either. Though there are crucial differences worth noting.

In the last two decades, Hungary-China relations have been gradually expanding and a collective notion of China as an important economic partner emerged, shared by most parties across the spectrum. The prospects of Chinese investment and economic benefits overshadowed the ideological and value-based differences for years, up until the controversial plans for a Budapest campus of Fudan University.

The case of the Chinese campus, which will be put to a referendum, gave a great indication that Orbán’s China policy is not necessarily in line with Hungarian citizens’ interests. In fact, according to a comprehensive study on Hungarian public opinion, 49 percent of respondents see China negatively while only 26 percent expressed positive views. Distrust in China was slightly higher than distrust in Russia – both standing around 50 percent as of the summer of 2021. Experts tend to agree that Hungary’s China policy is primarily driven by Orbán’s personal calculations and does not really reflect public attitudes.

When it became clear that the relations with China did not deliver on the economic promises, Orbán managed to utilize it politically. The close ties to China provided him with some room to maneuver inside the EU and earned Hungary disproportionately large international attention. Domestically, the government attempted to frame its vetoes on common EU positions regarding China as the nation’s struggle for independent foreign policy. Hungary’s relationship with China thus served Orbán domestically, somewhat on the EU-level and certainly internationally.

Recently, Minister of Foreign Affairs Péter Szijjártó’s phone call with his Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, reiterated the government’s objective. Szijjártó noted Hungary’s hopes to “further upgrade the level of mutually beneficial cooperation between Hungary and China.”

“America is in decline, while China is getting stronger,” Orban himself noted. “Hungary, with 10 million, has to maneuver skillfully in such a period.”

However slight or meaningful it might be, there is a lingering risk due to the lack of popular support behind Orbán’s China policy that should not be forgotten. Reviewing some of the main issues of the relations under Orbán’s leadership might give a clue on lessons to be learned.

Twelve Years, Four Takeaways

Looking at the broader picture of Hungary-China relations in the past dozen years, four main conclusions emerge.

Economically, the ambitious “Opening to the East” policy did not deliver and Hungary remains reliant on the EU market. At present, China’s share of Hungarian exports remains under two percent. By the end of 2020, the negative trade balance between Hungary and China stood at $6.32 billion (almost 60 percent of total trade volume) despite the continuous growth in the economic partnership.

Politically, the 16+1 cooperation framework between China and Central and Eastern European countries seems to be fading as signaled by unenthusiastic attendance at the latest summit followed by Lithuania’s withdrawal. The European countries’ dissatisfaction and the miscalculations on both sides are likely to lead to a quiet dissolution of the platform and a return to bilateral relations. This development might be rated favorably by many EU capitals who previously accused the format of dividing the EU, but it is unlikely to meaningfully impact the direction of Hungary’s China policy. Despite the gradually growing disillusion in the region, Orbán remains a supporter of the initiative. His government will still have to calculate the message the platform’s disappearance will send.

Also, China’s infrastructure projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Europe are increasingly controversial and have offered little tangible results. China’s regional flagship project, the Budapest-Belgrade railway is still yet to start in Hungary despite Serbian sections recently completed and Orbán taking a ride on the train with Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić. In 2020, the Hungarian parliament classified the studies of the feasibility of the Hungarian part of the project and the loan agreement, casting serious doubts about its profitability and the corruption risks. The project remains a sensitive issue for both sides, that is likely to gain attention from time to time despite the efforts of Fidesz to divert attention.

Finally, Hungary appeared to stand against the mounting security concerns and US pressure to exclude Chinese companies, Huawei and ZTE, from telecommunication infrastructure projects. Indeed, this is despite recent discoveries that revealed Budapest was not without its own concerns. While Minister Szijjártó announced the opening of Huawei’s largest logistics center outside of China in Budapest, internally, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs circulated a memo calling for caution against using Chinese-made devices. The next Orbán government is likely to be called upon for an explanation to all involved in this controversy.

What to Watch

In the end, Orbán is likely to maintain Hungary’s current foreign policy despite mounting challenges.

However, one thing worth watching is the current recalibration of Berlin’s foreign policy agenda. As Germany remains Hungary’s number one economic partner, Berlin has a special role in Budapest’s foreign policy considerations. Germany’s political landscape with the newly elected government appears to be gradually more critical of China as it re-formulates its foreign policy. Whether a more dramatic paradigm shift will take place in the Bundesregierung on China because of Berlin’s failed analysis of Russia is likely to be an important factor in Orbán’s foreign policy strategy. Germany’s stance toward China will give an indication of how much room Orbán will have in his balancing act in the future.

Thus it is more likely to be Berlin, not Brussels, who can play an important role in stemming Hungary’s continued authoritarian turn.

Written by

Réka Koleszár

RekaKoleszarRéka Koleszár is a PhD student at National Chengchi University in Taipei, Taiwan and a Program Assistant at the European Center for Populism Studies. She holds master’s degrees in Political Science and International Relations with a focus on East Asia, has completed a traineeship at the Council of the EU, and has experience as a Program Assistant at the European Policy Centre.