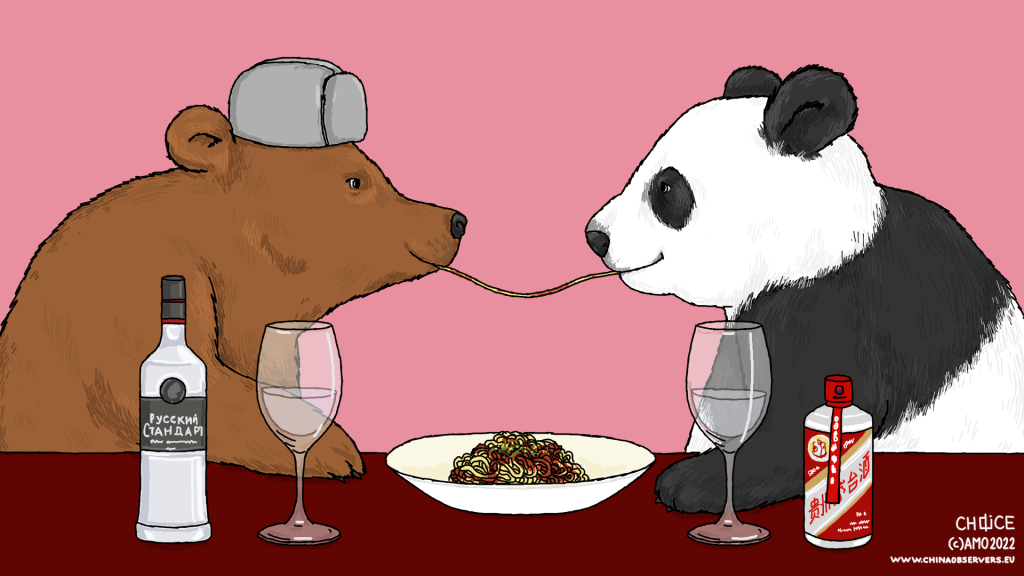

By providing political support for Russia amidst the invasion of Ukraine, Beijing made itself a notable part of the European security equation – if not directly, then as Moscow’s enabler. This new reality was addressed, correctly, with the EU’s strong and principled approach at the April 1 EU-China summit, drawing red lines to China’s potential involvement in helping Russia wage war. In order to remain credible, Europe should now craft potential responses to ‘grey zone’ support for Russia in restoring critical value chains, but also in the form of financial and material aid that Beijing might provide should Putin’s regime begin to crumble.

All Eyes on Beijing

The April 1 summit was a critical watershed moment for the EU’s approach to China – it finally became geopolitical. Within a long list of grievances, such as China’s economic coercion and personal sanctions, the issue of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine became the focal point of the EU’s agenda. The underlying message was clear: the future of China’s relations with Europe hinges on Beijing’s response to Russia’s aggressive behavior.

The EU’s strong and principled approach was provoked by Beijing’s thinly-veiled political support for Russia, augmentation of Moscow’s propaganda efforts, and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s claims about a “no limits” relationship with Russia “withstanding the test of changing international situation” just a day prior to the meeting. Chinese attempts to bring the conversation back to economic cooperation and mutual global interests proved futile, resulting in an exchange that Josep Borrell famously dubbed a “dialogue of the deaf”. The EU’s message was clear. The bloc declared it is finally ready to sacrifice a ‘positive agenda’ in relations with China by putting the fundamental interest of European security first.

Soon, however, Europeans might need to back this rhetorical shift with substance.

Commenting on the summit, the EU’s leadership warned against “any support to Russia’s ability to wage war.” It declared that “any attempts to circumvent sanctions or to aid Russia by other means must be stopped.” Intended or not, the official EU messaging to China is equivalent to a certain set of red lines that, if crossed by Beijing, demand action. No response to potential future acts of support to Russia, or China’s help in circumventing the sanctions, will translate into heavy damage to the EU’s credibility that Beijing may use to its advantage. Therefore, the EU must brace for using its power to hold the Russia-China axis in check.

So far, the sanction regime and strong political messaging coming from the West, including Europe, appear to be working. Despite China’s frequent official criticism of the sanctions imposed on Russia, Chinese companies and banks seem perfectly willing to comply with some of the sanctions, fearing both the potential political fallout and the impact on their global operations. Six weeks into unprecedented sanctions imposed on Russia, Beijing has not thrown Moscow an economic lifeline.

However, Russia does not need China’s large-scale economic aid yet, primarily because of the energy ‘loophole’ in EU sanctions. After the initial shock coming from a flurry of financial restrictions and asset freezes, Moscow was able to impose strict capital controls and stabilize the ruble. As long as billions of euros of European payments for energy flow into Russia each week, there is no urgent need for a significant Chinese bailout. Second, as long as the EU does not target the Russian energy sector and the financial institutions facilitating its exports, China’s most fundamental economic interest remains unharmed. Beijing can thus maintain a steady flow of raw resources, constituting 89 percent of its imports from Russia.

Addressing the Grey Zone

With Russia’s economic isolation from the West incomplete, the biggest current challenge for the EU is to prevent China’s potential ‘grey zone’ support for Moscow. This concern is especially acute in areas that are already sanctioned, especially in bridging technological gaps.

In the medium and long term, Russia’s primary constraint in waging war in Europe is its import-dependent industrial base, which is shrinking rapidly due to corporate boycotts and export restrictions. This brings about a potential for Chinese companies not only to expand commercially in Russia – now less attractive due to declining local purchasing power and financial instability – but also for politically-induced help in reconstructing critical Russian supply chains. Beijing may also try to offer capital injections from China’s policy banks to key Russian enterprises, as it did in 2008 and 2014.

Advanced semiconductors, sensitive machinery, transportation, and chemicals imports – all now sanctioned by the EU and partners in US and Asia – can partially be replaced by Chinese alternatives. This concerns not only civilian tech, but also dual-use technologies that are often hard to discern on the trade level and are distressingly easy to conceal. However arduous, costly, and time-consuming this grand technological reorientation seems now, in the longer term, it can prop up Russia’s ability to wage war in Europe. China should be actively discouraged from breaking Russia’s technological isolation and commercial free-riding, as this will basically undermine Europe’s costly efforts to stop Putin’s aggression.

Should the EU proceed with a total energy ban on the Russian oil and natural gas, the ultimate weapon that can crush the Russian economy, the fate of the China-Russia economic relationship is also mainly in the EU’s hands now. In the years-long strive to de-dollarize bilateral exchange, the euro became Russia’s currency of choice to facilitate exports to China. In 2021 its share was as significant as 48 percent, with the latest China-Russia natural gas deal signed on February 4 also to be settled in EU currency.

The EU could potentially maximize the damage of the embargo by banning Russian banks that facilitate energy trade from SWIFT and prohibiting all energy trade settlements in euros. This – at least in the short term – will certainly also destabilize supplies going to China, and the sole threat of using this instrument can be raised as an argument in talks with Beijing.

Xi Jinping’s Dilemma

Should the hard currency inflow coming from energy exports to Europe deplete, the Russian economy will undoubtedly face a profound economic crisis. Such a crisis could well threaten the stability of Putin’s regime. In such a scenario, China will face a fundamental dilemma of historical magnitude.

Suppose Xi Jinping lets Putin – his closest ideological ally – fall. In that case, this will send an extremely negative signal through the party ranks and the pro-Russian Chinese public, especially before this year’s CCP Congress. Moreover, this will inevitably incur a rise of political instability at China’s northern border – turning Russia into a problem rather than a strategic asset that diverts unwanted US attention.

Conversely, if Xi decides to prop up Putin with a massive bailout and offers a broad use of China’s alternative systems as CIPS, he risks an immense deterioration of China’s relations with the US and the EU. This will not be an easy walk, as China has minimal experience in being a ‘lender of last resort’ to struggling partner economies, and risks speeding up its own decoupling from the West. However, Beijing may still give it a chance, in a major step in the process of building an alternative, Sino-centric economic world order.

The EU’s Tall Order

What instruments can the EU use to hold the China-Russia axis, at its current state, in check?

The first step was already made, with the EU communicating that the future of the relationship – and the potential to advance the ‘positive agenda’ – hinges on China’s actions towards Russia. However, this may soon demand real action, as China may interpret it as a bluff and try to call it. Beijing may still expect a weak Western reaction, counting on the EU’s fears about an open economic conflict. Here, Beijing will certainly look at the fate of EU sanctions towards Russia. If Europe completes the rapid punitive decoupling from Russia, willing to bear the cost, Beijing will think twice before crossing the red lines.

For now, Europe should focus on China’s potential ‘grey zone’ support in bridging Russia’s technological gaps, reconstructing key value chains, and injecting policy bank capital into crucial Russian sectors. Here, the EU should develop analytical tools that will enable it to track ‘grey zone’ support and focus on clear messaging, communicating potential costs to Beijing. This may include limiting the access to the EU common market and public procurement procedures, pulling out of key technological partnerships with China, etc. Europe could also reignite the debate on developing secondary sanctions instruments, as they seem to effectively discourage China’s technological giants from expanding on the Russian market so far.

European primary sanctions on Chinese companies and institutions involved in supporting Russia may seem like a no-go zone for many European countries – especially now, as the continent struggles with imposing sanctions on Russia. Despite internal problems, Beijing may still respond with an asymmetric retaliation aimed at intimidating the EU – just as it did with personal sanctions in 2021. A resulting tit-for-tat exchange may lead to a larger trade conflict, inflation, and further global instability.

However, should China decide to meaningfully and openly support Moscow’s aggression in Europe with financial, technological, or military aid, the adverse effects could be much more immediate – threatening NATO’s and EU’s security. Europe should then brace for this scenario by completing a thorough assessment of dependencies on China and speeding up the works on defensive instruments that are already in the pipeline, such as the anti-coercion instrument (ACI). It should also actively coordinate on the matter with its partners in Europe, the US, and the Indo-Pacific – an emerging coalition of countries interested in holding the China-Russia axis in check.

Written by

Jakub Jakóbowski

J_JakobowskiJakub Jakóbowski is the Coordinator of the Connectivity in Eurasia project, as well as a Senior Fellow at the China Programme at the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW), a public think-tank based in Warsaw.