Traditionally loose BRICS has faced serious problems on its road to expansion. Exacerbated great power competition, however, paves the way for such a scenario.

The war in Ukraine accelerated the global re-alignment of forces. China, Russia, Iran, and a host of less powerful, but nevertheless important powers in Eurasia, are adjusting to new geopolitical realities stemming from a more pronounced rivalry between the West and Russia. This serves as a major motivation behind reported talks on BRICS expansion.

Adding More BRICS

Russian media recently announced that Argentina was planning on becoming a BRICS member state. In June, it was revealed that Iran has officially applied for membership. Others, such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey, are likewise reportedly willing to join the organization.

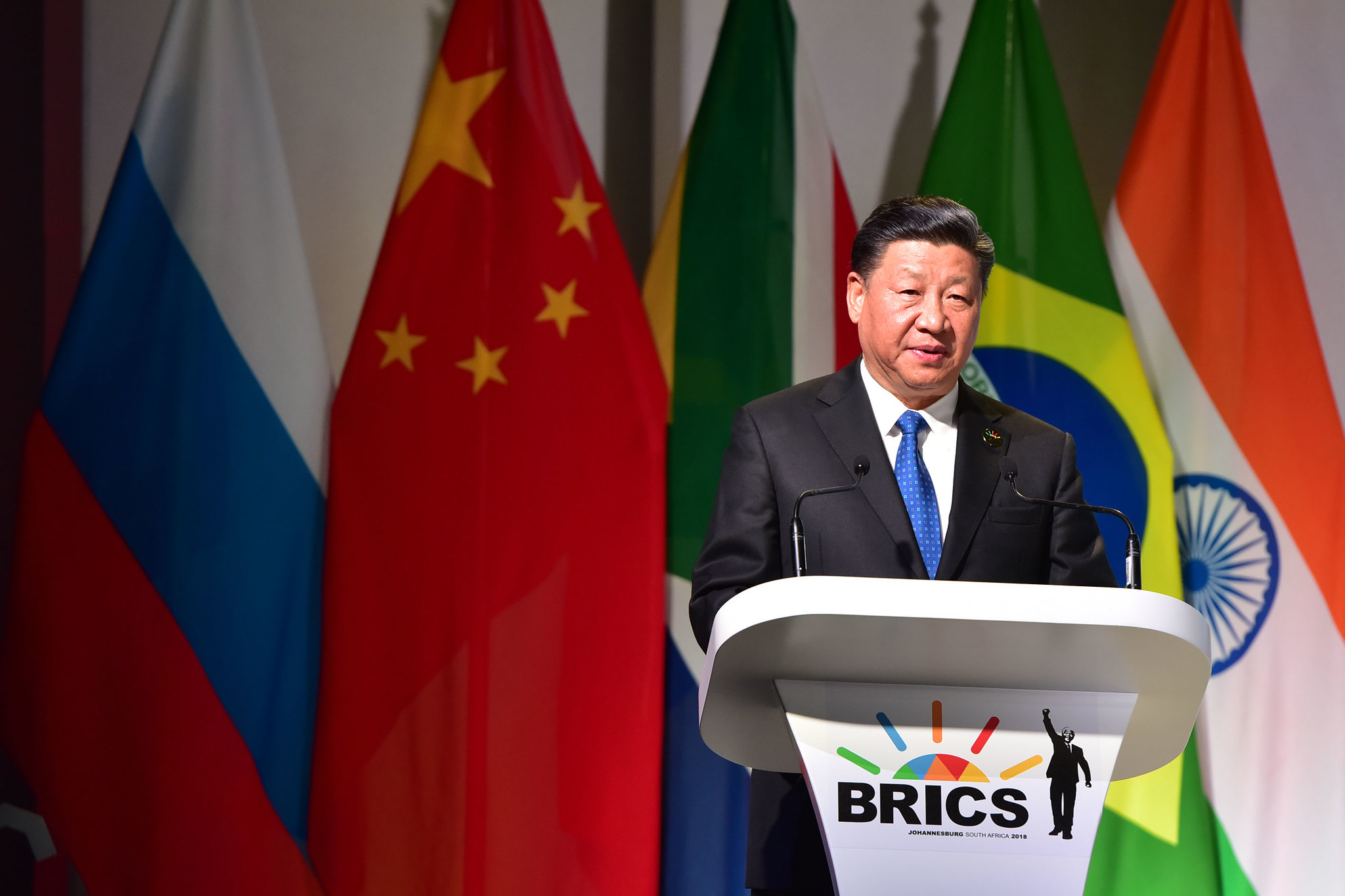

The BRICS consisting of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa was created more than a decade ago in an effort to shift the global geopolitics from the unipolar Western domination to a more diversified multipolar order. There seems to be a natural basis for such ambitions as the BRICS powers make up a significant percentage of the global population and economic productivity and possess enormous natural resources.

The intent to expand has been always present within BRICS, but the urgency to do so in the present moment is largely driven by accelerated great power competition. Amid the war in Ukraine, major powers are seeking new allies. Seeing unprecedented unity on the side of the West in responding to Russia’s aggression, China is fearful Russia’s military failures could reverse the global illiberal elan. Should Russia fail in its goals, the victorious West would be more confident and willing to join forces to contain China over Taiwan or more generally in the Indo-Pacific region.

The expansion of BRICS could thus be seen as a response to the changing global balance of power. The pandemic, China’s difficult ties with Europe and the US, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine put a strain on global economic growth. The BRICS states have been hit hard, with China’s economy stumbling following harsh COVID-19 lockdowns and real estate troubles. Thus, for Beijing, the BRICS expansion is about seeking additional markets to improve its position and involve other critical states with large populations and natural resources.

To be sure, China has always been willing to expand the grouping. In 2017, Beijing unveiled the BRICS Plus which aimed at building closer links with other emerging economies. Since then, however, the issue of expansion was sidelined till this year when China assumed the chairmanship. The 2022 summit hosted by China marked the first time that foreign ministers of non-BRICS countries (Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, UAE and several others) were invited.

From China’s perspective, the need for expansion is both a reaction to the current geopolitical re-alignment and the long-term objective to involve critical node states. The association or an outright membership of Indonesia, Turkey or Iran in the grouping would potentially limit the chances of them falling under excessive Western influence. Geographically, these countries have control over choke points through which a significant percentage of global trade crosses.

The Black Sea, the straits of Malacca and Hormuz are the focal points where the clash between revisionist and already established powers is unfolding. The BRICS’ intention to co-opt those states could thus be seen as solidifying the position of the grouping and its critical players, China and Russia, for the next, more exacerbated round of competition with the West.

A bit of propaganda is in play, too. Russia and China are eager to portray the grouping as a viable organization that aims at limiting the West’s influence. The plans for potential expansion fit into this narrative. China is eager to show that the Western sanctions are not working and that the rest of the world is not following suit. Beijing argues that the Global South is at least as powerful an actor as the West, believing that a careful policy of cooptation towards nodal states will help it achieve its global goals.

The present drive for enlargement also fits into China’s general push for expansion of other organizations where Beijing is effectively a leader. The Shangai Cooperation Organization (SCO) is a good example of Chinese ambitions where other Eurasian powers are expected to join the grouping. From the Chinese perspective, expanded BRICS and SCO dilute Western power.

Mixed Prospects

It has long been argued that BRICS is hampered by its loose nature. The members of the grouping are not bound by concrete agreements and in some cases are competitors, too, if not outright rivals. The expansion would turn the BRICS into an even more encumbered political organization. With a significantly increased membership pool, it is unavoidable that internal divisions would increase, complicating efforts to achieve unity on global issues.

India and China share a number of unresolved issues including territorial disputes in the Himalayas. Beijing’s support for Pakistan, India’s arch-enemy, further unnerves India. Delhi is worried that the BRICS and its potential expansion will mainly serve Beijing’s goals to establish itself as a dominant power in the Global South and encircle India with the semi-military ports in the Indian Ocean, often referred to as the string of pearls.

Even between Russia and China, despite the expanding scope of their cooperation, there is a host of insecurities rooted in geography and economic asymmetry. It has been even suggested that after the invasion of Ukraine and cutting ties with the West, Russia could slowly be turning into China’s near-total geopolitical vassal. Central Asia is one area where bilateral tensions have been significant, though the two have largely managed to avoid an open clash.

Yet another example of different expectations is Beijing’s unwillingness to invest in its northern neighbor amid its invasion of Ukraine. China wants to help Russia just enough to keep its neighbor afloat, but not as much as to incur Western sanctions. This means that Beijing will stay largely highly pragmatic when it comes to Russia.

BRICS has so far also lacked legal procedures for expansion and it is unlikely that all five countries will easily agree to new rules. Even if the BRICS states and its prospective new members share strong reservations or even outright enmity toward the collective West, this does not, by itself, create conditions for coordinated action. For China, Russia and Iran’s vision of near complete revision of the present international system is undesirable and economically self-defeating. Beijing wants to see changes, but more limited in scope, which would not radically upturn the global economic order the country has been benefiting from.

Yet, despite the deficiencies of the grouping and its pronounced lack of unity, the strength of the BRICS could lie in the ambiguity of the rules. As opposed to NATO, EU and other Western organizations’ expansion, BRICS is not as much built on common rules but rather is motivated by two all-encompassing and quite flexible goals: accelerating the emergence of a multipolar world and expanding the space for mutually beneficial economic activity away from reliance on the Western markets.

Thus, BRICS’ loose nature might actually serve as a comfortable basis upon which future cooperation could be built. Such a formula fits into how major powers such as China, Russia, and India have operated. They purposefully avoid official alliances, which, in their view, would only constrain their ability to maneuver in the international arena. Ambiguity is what strengthens their position. A certain dose of geopolitical chaos, too, presents greater opportunities.

It still remains to be seen whether BRICS successfully expands. So far global shifts indicate the prospects are more promising than during previous attempts at enlargement. Much will depend on China – so far, hints indicate Beijing is willing to throw its weight behind the expansion.

Written by

Emil Avdaliani

emilavdalianiEmil Avdaliani is a research fellow at the Turan Research Center and a professor of international relations at the European University in Tbilisi, Georgia. His research focuses on the history of the Silk Roads and the interests of great powers in the Middle East and the Caucasus.