Will October Elections Change Poland’s Stance Towards China?

Poland is approaching parliamentary elections, which some deem one of the most important since 1989. The results could determine the focus of Warsaw’s foreign policy and its role on the international stage, especially within the EU. However, it seems that the vote will have little impact on Poland’s future stance toward China.

This article is part of a series from CHOICE focusing on the impact of elections on countries’ China policy.

With only a few days left before the parliamentary elections on October 15, the tensions on the political stage in Poland are running high. The campaign debate is dominated by internal issues, such as the rule of law or abortion rights. However, on a higher level, it also concerns the future of Poland as a geopolitical actor and its ties with key powers, as well as its positioning within the EU.

Shadow of the Ukraine War

What might be the impact of the vote on Warsaw’s stance towards Beijing? While public debate on Sino-Polish relations is still practically non-existent in Poland, over the past few years, it was mostly two events that have catalyzed the realignment of views about China and the related risks and opportunities.

In 2019, a Huawei employee was arrested in Warsaw. The incident sparked a short-lived debate about whether it was wise for the Polish government to undertake such action, as Poland has firmly aligned itself with the US in the conflict with China.

Another turning point in views on Beijing was the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Warsaw has strongly supported Kyiv, and China’s ambiguous stance on Moscow’s role took some Polish politicians aback.

Speaker of the higher parliament house, Senat, Tomasz Grodzki described China’s stance as the ‘quiet player’ in this conflict. This understanding, shared by the majority of politicians, led to the realization that China is no longer just an economic partner but also a growing systemic rival, and, what is more, a potential military threat as well. This stance can be found among the most popular political groups – currently ruling conservative and Euroskeptical Law and Justice (PiS), liberal Civil Coalition (KO), centrist Third Way coalition, and the Left.

The only party departing from this basic consensus is the far-right Confederation, which was initially unclear on the stance on Russian aggression at the war’s outset, with prominent members openly supporting Russia in the war. The party views this invasion as part of a broader conflict between the US and China and advocates for Poland’s neutrality, arguing that such a stance would facilitate business with all countries and ultimately serve Warsaw’s best interests.

Followers, Not Leaders

As proven by a recent MapInfluenCE analysis by the author, electoral programs of the five most popular political groups in Poland either do not mention China at all (KO, the Third Way, the Left) or mention it in passing, as an example of a country making investments in technology or progressing in development without environment protection restrains (PiS, Confederation). And even if Polish political parties recognize various issues related to China, they remain relatively silent when it comes to proposing adequate strategies on how Poland should respond to this challenge.

Still, a shared outlook on China becomes apparent among the majority of the parties.

PiS, KO, the Third Way, and the Left agree not only on China’s negative role in the Ukrainian conflict but also on the importance of maintaining economic relations with Beijing (advocating for their new, more balanced shape) or supporting Taiwan on the international area without a change in status quo. While the Confederation’s stance on China in the Ukrainian conflict is not entirely clear, its politicians also see China as a valuable source of investments and emphasize the need to avoid economic dependencies on Beijing.

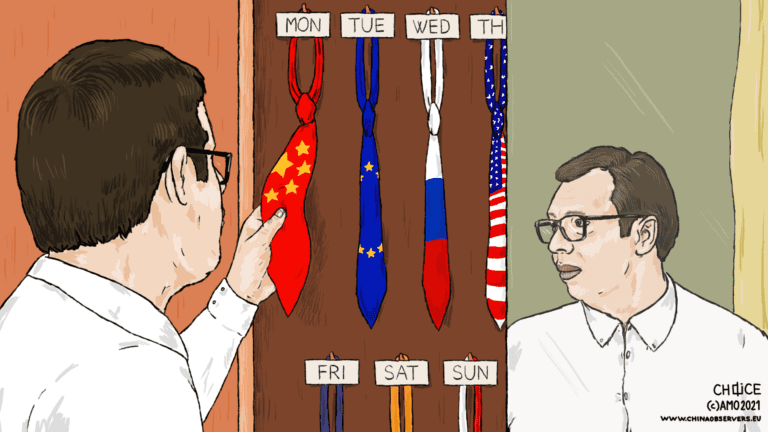

Generally, Polish political parties tend to align their China policies with key international actors, making choices based on their alliances with either the US or the EU, reflecting their broader worldviews. For instance, PiS’s Euroskeptical tendencies have spurred conflicts with Brussels throughout their seven-year tenure – and while the party professes support for a unified European approach on China, ongoing discord raises doubts about their ability to form a cohesive strategy within the EU framework. Additionally, while PiS displayed a more amenable attitude toward cooperation with the US during the Donald Trump era, their stance toward the Joe Biden administration remains uncertain.

On the other side of the spectrum, the majority of opposition parties – KO, the Third Way, and the Left – lean toward robust collaboration within the EU, striving to establish shared objectives in China policy. Meanwhile, the Confederation maintains a skeptical stance toward both the US and the EU and prefers a more independent approach for Poland.

Post-election Outlook

The latest polls suggest that even though PiS will receive the highest number of votes, it will be unable to secure an independent majority in the Sejm, the lower house of the parliament. It seems unlikely for PiS to form any kind of coalition, as both the party and its potential partner, Confederation, deny such a possibility. Nonetheless, even if PiS were to establish such an alliance, it might not be sufficient to govern.

In the event of PiS failing to constitute a government, the opportunity could be extended to the opposition – KO, Third Way, and the Left – which might comprise a ruling coalition together. However, uncertainty lingers, as these parties could still fall a few seats short of a majority. This scenario clouds the future of such parliament, with some speculating that it could trigger early elections in accordance with the constitution.

Regardless of the election’s outcome, Poland is likely to continue aligning itself with its Western allies in advancing its strategy towards China and shaping its policies. Depending on whether the current government or the opposition emerges victorious, the focus may shift toward different allies – either the US or the EU – in crafting foreign affairs objectives. Yet, a change toward shaping a distinct China policy will only materialize if the Polish government acknowledges the significance of crafting its own informed stance on this issue.

Written by

Joanna Nawrotkiewicz

nawrotkiewiczjJoanna Nawrotkiewicz is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Asian Affairs, Łódz University, Researcher at the Jagiellonian University, and an Expert for the CEE Digital Democracy Watch. She graduated from sinology and law at the MISH College of the University of Warsaw.