Duisburg: From a Dirty Old Town to Germany’s China City?

The German rust belt city of Duisburg has been at the forefront of cooperation between China and Germany. However, the uncertainty over the future economic engagement of Chinese actors in the city and the growing geopolitical risks increasingly put the future of cooperation into question.

This article is part of a series of articles authored by young, aspiring China scholars under the Future CHOICE initiative.

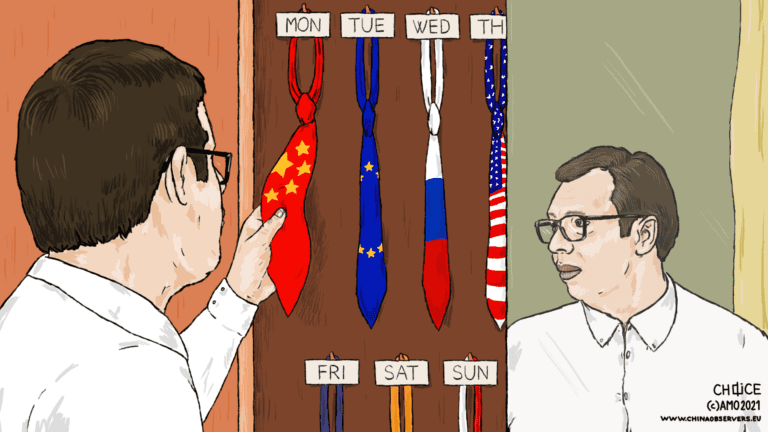

The recent approval by the German Chancellery of a major investment by the Chinese state-owned company COSCO in the Port of Hamburg, in the face of opposition from several ministries, illustrates the contradictions in Germany’s China policy between maximizing economic benefits and strategic political balancing. To fathom the effects of investments like the one in the port of Hamburg, which calls itself the “gateway to the New Silk Road“, one must look at the inland port of Duisburg, which is perhaps the best claimant to the status. The opportunities and risks of close ties to China for German and Europe can be demonstrated by looking at this example, especially considering recent developments concerning the ownership of the port of Duisburg.

The Making of Duisburg’s China Ties

Located at the confluence of the Ruhr and the Rhine, Duisburg is the westernmost city of the Ruhr Valley, Germany’s rust belt. The region, formerly dominated by coal mining and steel production, has been experiencing a severe and lasting structural crisis since the end of the 20th century. Today, the western Ruhr Valley is economically, demographically, and infrastructurally deprived. To cope with the city’s many problems, especially the high unemployment rate, Duisburg has two major assets to utilize: the world’s largest inland port and one of the largest universities in Germany.

The economic crisis of the Ruhr Valley hit the city of Duisburg particularly hard, as the local political and economic elites failed to react to the mounting challenges. As a result, the city increasingly fell behind. When the Duisburg inland port has been presented as an official part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) after 2013, local politicians seized on this enthusiastically. Although Duisburg’s connections to China go back to the 1980s, these contacts only became relevant in the 2010s. Regular train services between Duisburg and central China’s metropolis Chongqing began as early as 2011.

The logistical advantage of the Duisburg inland port is that cargo trains represent a middle ground between container ships and cargo planes in terms of price and speed. The infrastructure of the port of Duisburg allows goods to be transferred from river ships to trains directly. In this way, goods delivered by rail from China can be distributed quickly within Europe, and goods from all over Europe can easily be delivered to China by cargo train.

From the beginning, Duisburg’s political class, dominated by the left-wing Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the party to which the current German Chancellor Olaf Scholz belongs, has happily embraced Chinese interest in the port and the city. Chinese investment was seen as a development opportunity and a way out of the persisting structural crisis of the local economy. This development strategy was in accordance with the increasing focus of Germany on China as an important trading partner. The city set up a department for the coordination of Chinese affairs, reflecting the growing role of the agenda. The Lord Mayor of Duisburg, Sören Link (SPD), who took office in 2012, took it as a badge of honor to call Duisburg Germany’s China City. Local politicians are particularly proud of the fact that even Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Duisburg in 2014 and signed the town’s Golden Book. The engagement goes beyond commerce. The key actors in the local economy, such as the city marketing office or the chamber of commerce, have regularly organized a China festival to introduce the residents of Duisburg to Chinese culture.

Duisburg: Germany’s China City

The integration of inland port Duisburg into the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative and its enthusiastic reception by local politicians has left visible and invisible traces in the city, its structures, and institutions. The engagement with China has mostly manifested itself in three key areas: the local economy, academic cooperation, and cooperation through the city administration.

The increasing intensification of train traffic on the Duisburg-Chongqing route was accompanied by the settlement of Chinese companies in the city, especially in the port area. With over 100 Chinese companies, Duisburg is now the hotspot of Chinese investment in the Rhine-Ruhr region. The Chinese companies are mainly active in wholesale, warehousing, and other logistics-related sectors, with Duisburg developing into an important logistics hub. The structure of the local economy has changed and now 40,000 jobs in Duisburg are dependent on the inland port, whose main business is China trade.

The University of Duisburg-Essen has already had an Institute for East Asian Studies, the In-East, since 1984. With its focus on economics and geography, its graduates have increasingly been meeting the human capital needs of the city in recent years, which have been fueled by the inland harbor. Since 2009, the university has also hosted a Confucius Institute financed by China. In addition to the academic engagement with China and the provision of Chinese expertise to German students, more than 2,000 Chinese citizens are now enrolled at the university, mainly in engineering fields. This means that Chinese nationals make up 5 percent of the students at one of the largest German universities, leading among foreign students. Together with Chinese businesspeople settling in the city, this has led to a formation of a significant local Chinese community, which is increasingly making its mark on the cityscape. Their purchasing power has led to the establishment of numerous Chinese supermarkets, restaurants, milk tea shops and other establishments. Neudorf, the district near the university, is now known as China Town.

The cooperation between Duisburg and China has also spilled over into other fields. The city administration of Duisburg signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Chinese company Huawei in 2018. This MoU was initially kept secret and only released to the public after massive pressure but is no longer available online. Huawei was tasked with providing “innovative information and communication technology solutions with a partner ecosystem” and developing “projects for smart and safe cities.” The Chinese technology company was to help Duisburg become a smart city based on the Chinese model. This would have tied Duisburg’s city administration to Huawei through its software infrastructure. As far as is currently known, no projects have been implemented as part of the cooperation, but the thrust of the development is clear.

At the Crossroads

Due to its close ties to China, Duisburg has achieved remarkable success in structural change over the last ten years. By using its location potential, the city has developed a specialization as a logistics hub for Chinese trade, which would have had the potential to lift the city out of its economic malaise, was it not for recent global crisis developments.

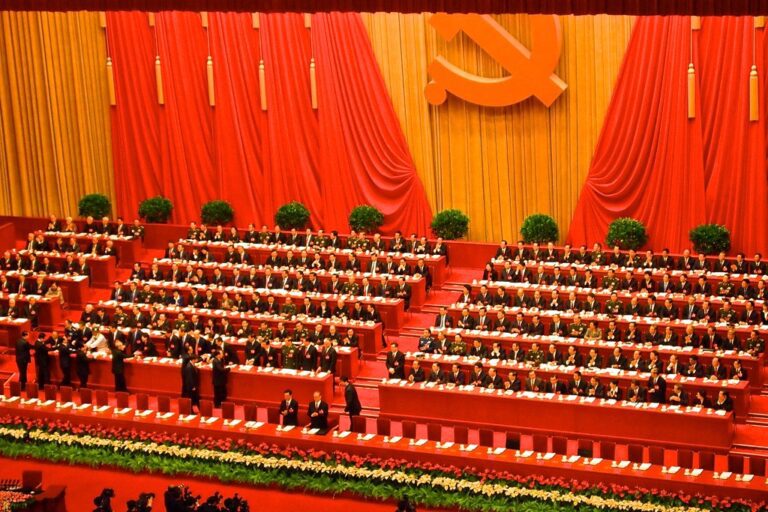

The COVID-19 pandemic and the persistent Chinese dynamic zero covid strategy have made it more difficult for German companies to trade with China. Although Germany’s trade volume with China is still growing, the discourse in Germany makes the political environment for business with China appear increasingly volatile. The report of the Chinese leader Xi Jinping at the recent Communist Party Congress that put emphasis on security issues over the country’s economic interests illustrates that trade and investment flows between Germany and China are situated in an increasingly geopolitically charged environment.

A further indicator of the uncertain future of Duisburg’s development strategy is that COSCO has sold its shares in the port of Duisburg. It is not clear whether this will mark a withdrawal of the Chinese economic engagement from the city, but it poses larger questions about the sustainability of China-focused development strategy.

Still, apart from the risks for the local economy if it becomes too dependent on trade and investment with China, the strategic risks for Germany in the case of Duisburg are rather low. The Duisburg port may be the largest inland port in the world, but the logistical importance for Germany and Europe is rather small, as the port handles less than half the cargo of the port of Hamburg and less than 15 percent of the port of Rotterdam. Chinese investments in Duisburg are also rather unproblematic, as they are mainly concentrated in low-tech sectors such as warehousing. Drawing parallels to cases like Kuka is therefore inappropriate.

Nevertheless, as the case of Duisburg shows, the risks are clear when a city becomes dependent on China for jobs and investment. The question arises whether Chinese capital could be withdrawn in the context of the emerging geopolitical conflicts of the coming years. In this regard, local actors are nervously looking at the sale of COSCO’s shares in the Duisburg port. The complete focus of the local political elite on China as the driving force of regional development, as evidenced for example by the China strategy planned for 2019, shows how dependent the city already is, at least in the minds of its leadership. Most worryingly, the city considered digitizing its administration with Huawei’s help at a time when the debate over the security of the cyber infrastructure had already flared up, showing a lack of risk awareness and strategic thinking. The ramifications of Beijing’s influence also became clear when the reading of a book about Xi Jinping at the local university was cancelled due to pressure from China.

The case of Duisburg thus illustrates that even seemingly unproblematic engagement with China can have problematic effects. Germany will have to decide soon whether it wants to prioritize business as usual with Beijing or whether it will take the new era of geopolitical and geoeconomic rivalry between China and the West seriously and draw the necessary political conclusions.

Written by

Tim Hildebrandt

Tim Hildebrandt is a Ph.D. candidate in political science and economics at the University of Duisburg-Essen and a Research Associate at the Ruhr West University of Applied Sciences. His research focuses on the intersection of politics, economics, and geography.