At the end of last year, the European Economic and Trade Office in Taiwan published its EU-Taiwan Relations brochure for the year 2021. One of the statements in the chapter on Taiwanese companies’ investment in the EU came as a surprise for many: by 2020, the Netherlands held the largest Taiwanese FDI stock in the EU, accounting for 49 percent of the total investments from Taiwan to the EU, while Hungary came in second place with a share of 18.8 percent.

While the Netherland’s position doesn’t require further explanation (as it is one of the world’s most attractive destinations for foreign investment, mainly for regulatory reasons), Hungary’s position is perhaps less understandable at first, given the country’s firm support towards China. The question arises: Why do Taiwanese companies choose the most China-friendly country as a major investment location in the EU?

Numbers Tell the Story

The socio-economic transition of Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries since the 1990s transformed the region’s external economic relations. Although most investors in the CEE initially arrived from Western Europe, the first phase of inward East Asian FDI also came soon after the democratic transition of 1989, with the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Poland (CEE3) among the most popular destinations. While smaller Taiwanese companies established their CEE3 presence already in the 1990s, bigger companies, especially Taiwanese multinational enterprises (MNEs) gained their foothold here after the millennium – at exactly the same time as Chinese companies.

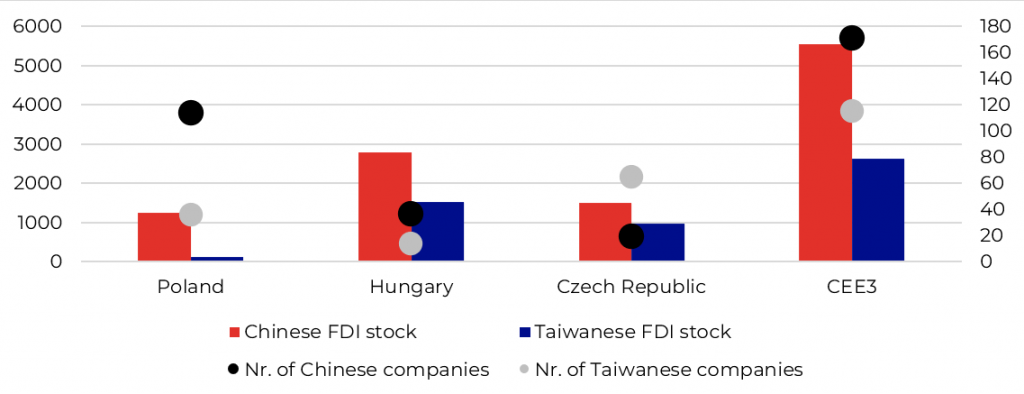

By 2020, CEE3 countries had accumulated more than $5.5 billion in Chinese FDI and more than $2.6 billion FDI from Taiwan, with Hungary receiving the most, followed by the Czech Republic and Poland.

Interestingly, the total number of companies shows a somewhat opposite trend: Poland has the highest number of Chinese companies, followed by Hungary and the Czech Republic, while the number of Taiwanese companies is the highest in the Czech Republic, followed by Poland and Hungary. That is, Hungary has the highest stock of FDI from both China and Taiwan, while it hosts only a third as many Chinese companies as Poland and a quarter as many Taiwanese companies as the Czech Republic. The explanation is relatively simple: Hungary hosts mainly big MNEs from both China and Taiwan, with each of these investments having a relatively high value, while Poland and the Czech Republic host mainly smaller companies.

When calculating percentage shares, we found that Chinese FDI stock is around or below one percent of total inward FDI stock in the CEE3 countries – it is above one percent only in the case of Hungary. Taiwanese FDI stock is less significant than Chinese but has also been increasing. Again, Taiwan’s share of total FDI in the CEE3 is above 0.5 percent only in the case of Hungary.

Chinese and Taiwanese FDI stock and number of companies in CEE3, million USD (left axis) and number (right axis), 2020

Factors of Attraction

The main entry modes and sectors targeted by Chinese and Taiwanese investment are similar in all CEE countries, although they are more diverse in the most popular target countries. Just as Western European investors, both Chinese, and Taiwanese investors typically target CEE3 countries for electronics manufacturing or assembly of machinery and transport equipment.

As regards those factors that attract FDI to CEE3, one can find many similarities between Chinese and Taiwanese MNEs. The labor market is to be considered first, since a skilled labor force is available in sectors (mainly manufacturing) in which Chinese as well as Taiwanese interest is growing, with labor costs being lower in the CEE3 than the EU average. Similarly, corporate taxes can also play a role.

Still, the main type of both Chinese and Taiwanese FDI in the CEE3 seems to be a market-seeking investment: by entering these markets, companies have access to the whole EU market or even global markets, through free trade agreements between the EU and third countries. Another aspect of EU membership that has induced Chinese as well as Taiwanese investment in the CEE3 is institutional stability, that is, these countries offer greater planning and property rights security, as well as dedicated professional services that can support business development. Chinese companies also appreciate business agreements that are supported by the respective host country’s government.

While political relations have influenced Chinese MNEs’ investment decisions, Taiwanese companies seem to be less concerned about the level of political cooperation. In the interviews by the authors of the research, almost all sources stressed that Taiwanese companies, especially the big ones, act in a highly pragmatic manner. This means that they do not really care about political relations between Taiwan and the host country but focus purely on their business interests.

Destination Hungary

The example of Hungary deserves particular attention. Compared to the previous Socialist government, the ruling Fidesz party has doubled subsidies to multinational companies and has been particularly keen to entice electronics and automotive manufacturers, with each job created receiving significant public subsidies. Orbán’s Fidesz, however, also strengthened relations with China, and as a result, relations with Taiwan are considerably less developed than in Czechia or Poland.

However, rules in politics and business are different As confirmed by one of the Taiwanese companies’ representatives based in Hungary Taiwanese MNEs in fact receive the same subsidies as the Chinese do. Given the pragmatic strategy of Taiwanese MNEs, such incentives could indeed explain why Hungary is a relatively popular destination in Europe for Taiwanese companies, despite its political indifference – or even unfriendliness – towards Taiwan.

Of course, political relations do matter but only up to a certain point. Due to the relatively positive stance the Czech Republic has adopted towards Taiwan, the country is quite popular among Taiwanese people. This positive perception of the Czechs has influenced the location decisions of some Taiwanese companies. However, this tendency is more typical of smaller companies, while large MNEs seem to follow a different logic.

The few big Taiwanese MNEs with a presence in CEE seem to choose Hungary rather than Poland or the Czech Republic for their investment, even if political relations are coldest there. One of the interviewees explained this by pointing out connections between Chinese and Taiwanese companies both globally and locally. That is, the majority of the big Taiwanese MNEs in the CEE3 – such as Foxconn, Giant, Sinbon, and Yageo – have a connection to China: either a production facility or a subsidy is located on the Chinese Mainland, or they have some kind of cooperation with a Chinese company globally. As a result, these Taiwanese companies often follow the ‘Chinese way’, that is they behave in a similar fashion to their Chinese counterparts, make similar decisions when it comes to location choice, or even follow Chinese companies to a specific – in our case CEE3 – location. These companies are learning from their Chinese partners’ experience, leveraging these contacts, and taking advantage of the results their Chinese partners have already achieved there. Moreover, since Taiwanese multinationals do not want to risk their already existing relations with Chinese partners, they are “keeping a low profile” in CEE and do not even emphasize their ‘Taiwaneseness’.

It is a twist of fate – and a feature of democracy – that in the event of a deteriorating political relationship, Chinese companies and institutions obey the Chinese state and almost immediately leave the country deemed inhospitable (see Lithuania’s case), while Taiwanese companies in a similar situation not only stay but even bring new investments to a country that has not been a politically welcoming host for a long time. If Taipei would ever wish to translate its economic links into diplomatic gains, then persuading Taiwanese MNEs to act patriotically – even at the expense of Taiwan-China corporate relations – appears to be the first step to take.

This article is based on the research project “Economic impact of Engagement with Taiwan – A Comparative Study,“ coordinated by Academia Sinica, supported by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR) in the UK, and the U.S. Department of State. The views expressed in the article do not reflect the position of the IWPR or the US State Department.

Written by

Ágnes Szunomár

Ágnes Szunomár is an Associate Professor at the Institute of Global Studies, Corvinus University of Budapest, and a Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of World Economics, HUN-REN Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Hungary. She is also a CHOICE Fellow for Visegrád countries.