In recent months, China has been trying to mend ties with Poland, negatively impacted by the Russian war in Ukraine, but with limited success. Representing the same political camp, Poland’s President Andrzej Duda and the government of Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki have demonstrated different interests vis-à-vis China. However, this dual-track policy has become increasingly alike after the Russian invasion, demonstrating how China’s alignment with Russia complicates relations with Poland and, in the broader perspective, with Central and Eastern Europe and the West.

Tensions over Ukraine

On July 29, Chairman of the People’s Republic of China Xi Jinping held a phone call with Poland’s President Andrzej Duda. China’s leader, who initiated the call, recalled President Duda’s presence at the Beijing Winter Olympics opening ceremony, called Poland “a priority cooperation partner in Europe” and pointed out the prospects of bilateral cooperation, including trade, economy, and connectivity.

The Chinese readout only briefly mentioned that “both sides exchanged their views on the Ukrainian crisis.” In contrast, according to the information provided by President Duda’s office, an over one-hour conversation was dominated by the consequences of the Russian aggression on Ukraine. To this end, Duda emphasized the negative security and economic impacts the war waged by Russia has on Central and Eastern Europea (CEE), including its trade relations with China. The Polish President also pointed out Russia’s attempts to weaponize a global food crisis and highlighted China’s ability to play an active role in preventing it. The call showed how from the Polish perspective bilateral ties have been severely negatively affected by the war in Ukraine, with Warsaw expecting China to change its course on the issue.

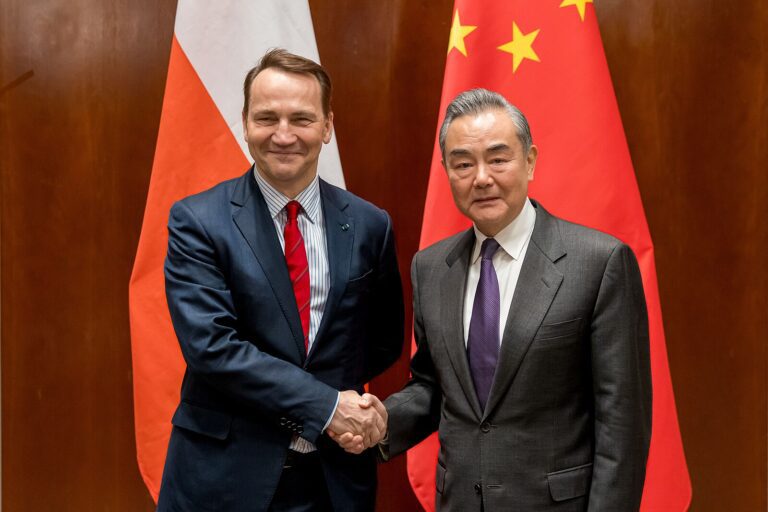

The same conclusion can be drawn from the video call held in early June between Polish Foreign Minister, Zbigniew Rau, and his Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, as part of the 3rd Plenary Session of the Poland-China Intergovernmental Committee, a dialogue mechanism established as part of the Sino-Polish “comprehensive strategic partnership.”

When it comes to the Russian aggression toward Ukraine, the Polish Foreign Ministry stated that both Poland and China have noted “the differences in voting at the United Nations,” referring to China’s tacit support of Russia by stating that Warsaw was calling on every nation which supports the sovereignty and territorial integrity to strongly condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The appeal of the Polish side, a country at the vanguard of military and humanitarian assistance to Ukraine (Poland is currently hosting some two million refugees from Ukraine as since the outbreak of the war, its border has been crossed by close to 4.8 million Ukrainians) is therefore clearly communicating Warsaw’s dissatisfaction with China’s approach to Russian aggression.

Apart from the discussions on the Ukraine issue, Zbigniew Rau relayed to Wang Yi a list of economic problems that Poland had waited for China to address for a number of years. This includes reducing the enormous trade gap with China, the increased inflow of Chinese FDI (particularly in greenfield projects), improved access to the Chinese market for Polish products, and greater participation of Polish firms in the operations of the China-Europe railway network.

Still, it needs to be stressed that tensions in Poland-China relations emerged well before the war in Ukraine. Poland’s government has been at the forefront of China’s technological containment in CEE for a number of years. In January 2019, it arrested a Chinese employee of Huawei on allegations of spying. In September of the same year, Poland became the second country in CEE, following Romania, to sign a joint declaration on 5G networks, which indirectly targeted the Chinese telecom giant.

Rumors of Chinese Assistance

Russia’s aggression has created a new contentious issue that looms large in the relationship. In reaction, China appears to have sought to offset the impact of the disagreement, so far with limited success.

In May, the Polish Foreign Ministry did not receive the Chinese delegation which arrived in Warsaw on the last stop of a three-week diplomatic tour to eight CEE countries aimed at assessing the region’s attitude toward China and the future of the troubled 16+1 format. Unsurprisingly, the delegation’s arrival in Poland was not reported on the website of China’s embassy in Warsaw. Instead of meeting the Polish Foreign Ministry representatives, the delegation headed by China’s special 16+1 representative, Huo Yuzhen, met with Polish lawmakers, including the head of the Polish-Chinese parliamentary group Marek Suski (Law and Justice), and Sławomir Majman, the deputy head of the Institute for Security and International Development.

Three weeks after the visit of the Chinese diplomatic mission, Marek Suski while criticizing the EU for its alleged ineptness on Polish Television (TVP), unexpectedly declared that based on his prior talks with Chinese diplomats, China was ready to provide financial and material help to Ukrainian refugees in Poland. According to Suski, the Chinese local governments were asking their Polish partners about what kind of help was needed. Three months on, this dubious statement has still not been verified.

According to Suski, the amount of proposed aid from China was to be relatively small, but it was to symbolically show that China was not blindly supporting Russia. It cannot be ruled out that China has been trying to fly under the radar and employ local connections with Polish counterparts to improve both the country’s image, blighted by its alignment with the Kremlin, and to underpin the continuity of the 16+1 format.

One can also speculate that China’s promises are driven by the aid for Ukrainian refugees delivered by Taiwan, or the involvement of the New Federal State of China, an anti-CCP movement founded by fugitive billionaire Guo Wengui and Steve Bannon, whose volunteers have been helping the refugees on the Ukrainian-Polish border. No matter China’s actual intentions, the assistance signaled by Marek Suski has so far not materialized.

China has recently been attempting to put a positive spin on relations with Poland in its external propaganda as well. For example, following the foreign ministers’ call, the Chinese Ambassador published an op-ed in Rzeczpospolita daily newspaper, where he envisioned excellent prospects for bilateral relations but only briefly referred to the “bourgeoning Russian-Ukrainian conflict,” which, coupled with the COVID-19 pandemic, has caused disruption in the global geopolitical and economic arenas. Furthermore, Liu Zuokui, one of the top CEE experts from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, published an opinion piece in China Daily without a single reference to the war in Ukraine, praising Poland as one of China’s important partners in CEE as well as the EU and an essential actor in boosting Eurasian connectivity. Interestingly, both Wang Yi and the media also recalled President Andrzej Duda’s attendance at the Beijing Winter Olympics opening ceremony as an important marker in bilateral relations.

Two China Policies

On the Polish side, a dual-track policy on China seems to have developed in the recent years, which has sometimes muddled the picture of the relationship. Though representing the same political camp, the president and the government have on several occasions demonstrated different, if not contradictory, attitudes towards China. It is likely that these differences are a result of diverging interests rather than of a coordinated policy.

In early 2022, as Russian troops were massing near the Ukrainian border, President Duda was the only leader of an EU country to participate in the opening ceremony of the Beijing Winter Olympics and to meet Xi Jinping. The visit occurred despite a number of Poland’s Western partners boycotting the event over human rights violations in China, especially the crackdown on Uyghurs, which several countries regard as genocide. Apart from President Duda, over thirty other leaders also attended the ceremony, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, with whom Xi Jinping signed a February 4 joint communique, labeled an “autocrats’ manifesto” by former NATO Secretary-General Anders Fogh Rasmussen. Many observers viewed the Polish President’s visit as tantamount to Poland breaking away from the Western Bloc at a critical moment for Eastern European security.

Indeed, the context of the visit was unfortunate on many levels. It came at a time when the Chinese party-state media and “wolf warrior” diplomats were discrediting European security architecture and actively repeating Kremlin propaganda, blaming NATO for the onset of “the Ukrainian crisis,” which was to turn into a hot war just a few weeks later.

Ahead of President Duda’s China trip, his foreign policy advisor Jakub Kumoch explained that it was Poland’s sovereign right to conduct “its own politics towards China,” arguing that the “very friendly relationship” does not contradict Poland’s alliance with the United States. After the visit, the presidential minister, Andrzej Dera, explained that apart from economic issues, President Duda “presented to Xi Jinping the crisis around Ukraine from European and NATO perspectives, as China’s president arguably only has information from the other [that is the Russian] side.”

However, as noted by the news portal Onet, President Duda’s commitment not to antagonize China might have been, to some extent, driven by his personal ambitions. Andrzej Duda will conclude the second and last term of his presidency in 2025 and there is speculation that the most significant opportunity for Duda to further his international political career after he leaves office is to take on a role in the United Nations.

To achieve this goal, the Polish President will need both the support of the US and at least a tacit consent of China. This is why, it is argued, Andrzej Duda has been consistently developing his relations with the US while striving to maintain solid ties with China whose human rights record he has never personally criticized. During the meeting in Beijing, Xi Jinping thanked Andrzej Duda for positively responding to the invitation received five years before, describing his relations with the Polish President as a gentlemen’s friendship that adheres to their respective commitments. It remains to be seen if Xi will reciprocate support for Duda’s international ambitions when the time comes.

President Duda’s China policy has often been inconsistent with that of the Polish government, which is in fact led by the president’s former political party, Law and Justice. For example, Rzeczpospolita hinted that ahead of the February 2021 summit of the 17+1 format, Duda dismissed the Foreign Ministry’s efforts to downgrade Polish representation and discourage him from taking part in the event hosted, for the first time, by Xi Jinping. The Polish Foreign Ministry failed to dissuade the president, who explained that “no important event concerning Central and Eastern Europe can take place without the presence of Poland.”

This was not the only time where the conflicting views on China came out to the open. In contrast to Duda’s accommodating views in June, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki published an opinion piece in Politico where he warned against the passiveness of the West towards Russian aggression, as the fall of Ukraine could have long-term consequences for the world order, in which “the US and Europe may be replaced by China – or China in tandem with Russia.”

In the face of war across its eastern border and the imminent threat from Russia, Poland is unequivocally striving to maintain its close security ties with the US and NATO. At the same time, Polish authorities are attempting to maintain the channels of political and economic cooperation with China, which may be used as leverage with the EU or the US, especially regarding tensions over the rule of law. Still, against the backdrop of China’s position on the war and its ties with Russia, President Duda seems to be adjusting his tactics and has become more explicit regarding China’s passivity in constraining Russia’s actions. Thus the president and Foreign Ministry’s respective narratives towards China become increasingly close, if not synchronized, demonstrating how the war in Ukraine is damaging China’s relations with Poland and the broader region.

Written by

Bartosz Kowalski

BartekKowalski1Bartosz Kowalski is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Asian Studies of the University of Łódź, Poland, and a Researcher at its Center for Asian Affairs. His research focuses on China’s foreign policy, including relations between China and Central and Eastern Europe.