War in Ukraine Brings Belgrade Closer to Beijing

This article is part of an exclusive new series from CHOICE focusing on China as a topic in elections across Central and Eastern Europe.

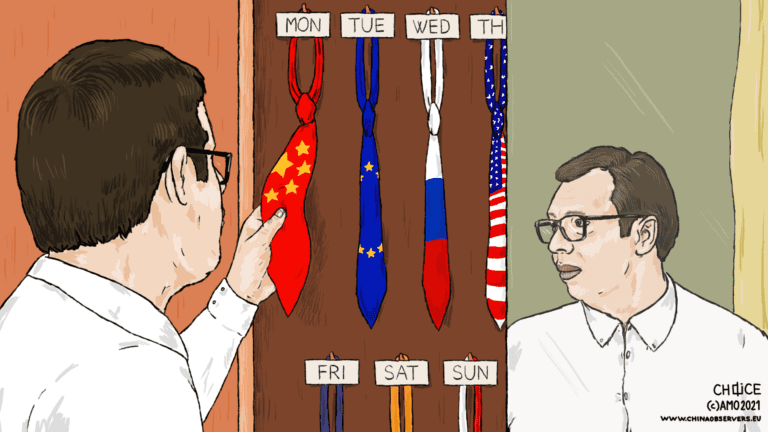

Russian aggression in Ukraine is not only a defining moment for the global order and power balance in international relations, but a likely turning point in Serbian foreign policy. In terms of the latter, the stalled invasion is clearly pushing Serbia away from Moscow and closer to Beijing.

As Serbia is to hold parliamentary and presidential elections on April 3, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has reshaped the campaign’s primary themes. One of the most hotly debated issues is whether Serbia will join the West and impose sanctions on Moscow, a move that would signal a stark shift in Belgrade’s attitude toward one of its most important international partners. While Serbia has not explicitly taken a stand against Moscow and has remained neutral for the time being, certain moves made by Belgrade’s decision-makers have indicated that Serbia may indeed strive to separate itself from Russia in the long run.

However, this move away from Moscow does not inherently imply a westward turn. Eventually, this might bring Belgrade to its other key partner to the East – China.

Moving Away from Moscow

As a traditional Russian ally in the region, Belgrade has found itself in a tight position amid Moscow’s belligerent action in Ukraine. Nonetheless, Serbia seems to have charted an approach that deviates from some of its long-standing norms in terms of Russia policy.

For example, Serbia voted in favor of a UN resolution condemning Russian aggression toward Ukraine on March 2. This was followed by Belgrade’s decision, for the first time since the Russo-Ukrainian hostilities began in 2014, to join the EU’s restrictive measures. Specifically, Serbia has aligned itself with the EU Council’s decision to extend sanctions against former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, who was suspected of being Putin’s desired pick to replace Volodymyr Zelenskyy, as well as other former senior members of the Ukrainian government from 2010 to 2014.

These actions by Belgrade have been interpreted as laying the groundwork for more concrete steps to distance itself from Moscow, especially as Western pressure builds.

The fact that the election campaign is underway is most probably the main factor holding back more vocal demands from the West that Belgrade acts quickly. At the moment, the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), led by incumbent President Aleksandar Vučić, looks likely to maintain power. However, whoever wins must devise a strategy to find a balance between Western demands to impose sanctions on Russia and Serbia’s tight ties with Moscow.

The additional problem is persuading the Serbian populace that Russia is not a partner with which Serbia should be affiliated in the long run. That will by no means be easy. Even at times of Russian aggression, the Serbian population maintains a high degree of support for Russia, with public events held to show support for Russia after the invasion.

Of course, there is an alternative option, in which Serbia refuses to align with the EU and the US and continues to have tight relations with Russia. This would make Serbia an outlier in Europe, further complicating the country’s EU integration prospects, and leading to possible isolation from the West. Some EU politicians, such as Lithuania’s Foreign Minister Gabrielius Landsbergis have even brought up the option of sanctioning non-EU countries such as Serbia if they were to circumvent the sanctions. As a result, it is unlikely that the new government will choose to maintain relations with Moscow at the same level as they were before the invasion, which might leave a vacuum for other actors to fill.

China as an Election Ace

The chief competitor for that role is, of course, Beijing.

While Russia is creating headaches for the Serbian leadership before the elections, cooperation with China seems to only bring benefits.

Serbian President Vučić met with Xi Jinping in Beijing after the Winter Olympic Games Ceremony on February 5, essentially using the opportunity to kick off his election campaign. The two leaders reaffirmed their countries’ “iron-clad friendship,” and announced new joint infrastructure projects and Chinese investments in Serbia. Both parties also expressed interest in signing a bilateral free trade agreement that is to be finalized by the end of 2022. Serbia could thus become a third country in Europe, after Iceland and Switzerland, to have signed an FTA with Beijing.

The ruling SNS and Aleksandar Vučić have mostly focused on the government’s economic achievements during the last ten years in their reelection campaign. “Dela govore,” which approximately translates to “our previous work speaks for itself,” is SNS’s key election theme. Here, infrastructure projects implemented in cooperation with China are a prominent element of their campaign efforts.

Serbian President, joined by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, attended the inaugural train ride from Belgrade to Novi Sad on March 19. This is the segment of the infamous Belgrade-to-Budapest railroad worth more than $3 billion that was agreed upon as part of China’s cooperation with Central and Eastern European countries. The Belgrade-Novi Sad section was built in two stages, using Chinese and Russian loans respectively, while the remaining section to the Hungarian border is to be financed by Chinese loans only. The campaign website of SNS both for the presidential and parliamentary elections even has an interactive map of infrastructural projects completed in Serbia, including those financed by Chinese funding.

Indeed, over the years, Sino-Serbian economic cooperation has grown significantly, with Chinese banks providing more than $8 billion in loan agreements for Serbian infrastructure projects. China has also invested more than $3 billion in Serbia through foreign direct investments between 2010 and 2020 and has become a significant foreign trading partner for the Balkan country, with annual trade exceeding $4 billion in 2020.

On the same day that the train arrived in Novi Sad on the Chinese-built railway, Serbian Infrastructure Minister Tomislav Momirović signed a $190 million commercial deal with China Road and Bridge Cooperation for the development of the Novi Sad bypass road. This demonstrates that Beijing and Belgrade are strengthening their cooperation even in times of crisis and that China will continue to be a trusted partner for the current administration and SNS leaders in the future.

The Pivot to Beijing

Serbia and China’s bilateral relations are flourishing, and they could grow even closer in light of recent events in Ukraine. If Serbia takes steps to distance itself from Moscow, Beijing will become Belgrade’s most important East Asian partner.

China already has a positive image among the Serbian people, especially following the Chinese assistance to Serbia in terms of deliveries of anti-epidemic materials as well as Chinese vaccines, which was played up by the local media and politicians.

Although Belgrade maintains a neutral stance in the Ukraine war and has not sanctioned or criticized Russia for its aggression, the new leadership will have to make a difficult choice of whether to distance itself from Moscow after the election. While Serbia would be unlikely to turn its back on Russia without the Western pressure, it might ultimately prove too much to bear, considering the risk of further isolation from the West and endangering the Serbian path to EU accession.

To sell the unpopular move to the population, the new government might focus even more on China in terms of its big power diplomacy, highlighting the tangible economic benefits. It thus appears that the “steel friendship” between Belgrade and Beijing will only get tighter.

Written by

Stefan Vladisavljev

vladisavljev_sStefan Vladisavljev is CHOICE Visiting Fellow. He is also the Program Coordinator of the Serbia-based non-governmental organization Foundation BFPE for a Responsible Society. He analyzes Chinese presence in Central and Eastern Europe with a special focus on Serbia and the Western Balkans.