CEE-China cooperation could be quite different after Lithuania’s withdrawal from the 17+1 platform.

As Prostetnic Vogon Jeltz and his crew of demolition spaceships were nearing Earth to make space for a galactic bypass, the dolphins attempted to communicate to the far less intelligent humans the impending doom of the planet. Upon failing to do so and dolphins’ leaving the Earth for an alternate dimension, humanity was left with a telling message. “So long, and thanks for all the fish.

In the present reality, only marginally different from the one envisaged by the author Douglas Adams, Lithuania bid adieu to the 17+1 and China’s fishy promises associated with the platform. Confirmation of the move by Gabrielius Landsbergis, Lithuania’s Foreign Minister, was accompanied by a parliamentary resolution labeling China’s treatment of Uyghurs and other minorities in Xinjiang a genocide. Rubbing salt into the wound, Lithuania is planning to open a representative office in Taiwan in the near future.

Torn between indignance and angst, Chinese state media went on the counter-offensive and labeled the Baltic country a Western “pawn” that is a “pivot point […] playing an active role in spreading fake news about Xinjiang”, a “politically radical” country and a “contemptible scoundrel”

Even as Chinese media may see Lithuania’s withdrawal as a ‘culling of the weak’, that will ultimately make the 17+1 a stronger and ever-more pragmatic platform free of interference, it opens three important questions about the future of CEE-China interactions, as well as the relations between the EU and China.

Which CEE countries might leave the platform next? Will the region muster a united push for a common EU policy on China mindful of small states’ interests? How will the EU incentivize the non-EU states of the Western Balkans to leave the 17+1 platform and prevent them from further normative backsliding? All remain open questions in desperate need of address.

Who’s Next?

To the observers of CEE-China relations, Lithuania’s announcement did not come as much of a surprise as it was repeatedly hinted at since at least this February when a high-ranking Lithuanian representative failed to attend the 17+1 virtual summit. The real cliffhanger is whether any other CEE country will follow suit and leave the platform as well.

The attendance sheet from the virtual summit already offers some insights. Besides Lithuania, five other states were represented at the summit ‘only’ at a ministerial-level: Estonia, Latvia, Romania, Bulgaria, and Slovenia.

Elsewhere in CEE, China has recorded sharp drops in favorability in the eyes of the public. In the Czech Republic, over 40 percent of the population has less favorable views of China now than three years ago. In Hungary, Slovakia, and Poland, between 40 and 50 percent of the population have either negative or very negative views of China.

Already lukewarm attitudes of politicians and plummeting favorability of China among the CEE publics do not profess much success for the 17+1 platform in the coming months and years.

As China’s foothold in the region is based on fostering ties with local political and business elites rather than systemic dependency, it is particularly brittle.

With upcoming general elections in October, and China being a strongly contested topic in the domestic political discourse, Czech Republic is one of the countries to watch. If the opposition bloc led by the Pirate Party manages to beat the current oligarch-turned-prime minister Babiš, the country’s China policy will probably be shaken to the core. We could already observe similar developments after the 2020 general elections in both Lithuania and Slovakia, which ushered in fast and resolute changes in their respective policies on China as the past opposition came into power, unseating the political elites China has been fostering for several years.

Dreams of United Europe

More pragmatically inclined politicians and observers may ask what the alternative platforms for CEE are to conduct relations with China. Even though many of China’s economic promises did not materialize, there is an undeniable benefit of participating in 17+1 – it provides a venue for the regular meeting between CEE and Chinese high-level representatives as well as platform for lower-level sectoral cooperation.

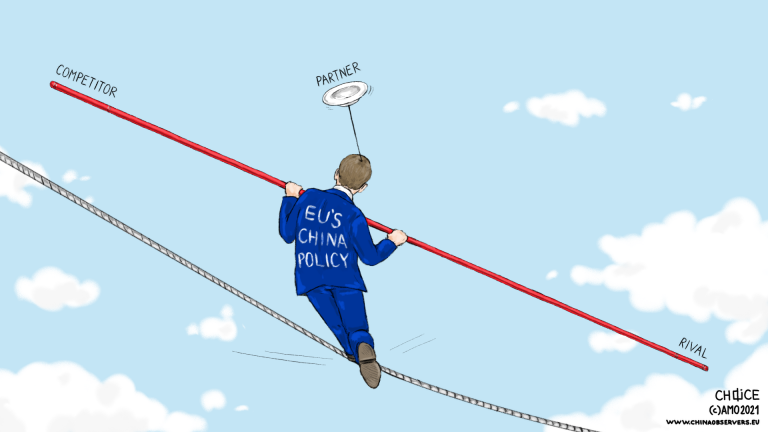

The idea of EU 27+1, which would provide a platform for all EU member states to engage with China, has often been cited as an example of a viable alternative to the 17+1 platform. The meeting along the lines in Leipzig which was originally proposed by Germany and planned for September 2020, was, however, postponed indefinitely. Instead of a joint meeting of all EU member states, the EU’s China policy has been steamrolled by the Franco-German tandem, which pushed through the CAI proposal, much to the surprise of both old and new member states.

Currently, it seems unlikely that Germans, French, or any other large member state, which already enjoy their privileged bilateral relations with China, will actively support and work towards a joint summit.

The idea of dealing with China within the EU27+1 framework was touted also by Lithuania’s Landsbergis. If it is to happen, the smaller EU member states from the CEE will need to band together and create a push to put the joint summit on the agenda. After all, the meeting would be in their interest, and giving up on their agency within the EU is destined to fail them.

No Country Left Behind

In discussing the future of the CEE-China relations, it would be a fool’s mistake to omit the Western Balkans.

Despite the vitriolic narratives, China is a rational actor. Thus, we can expect that it will engage in some sort of damage control caused by Lithuania’s withdrawal from the 17+1 and prevent other CEE countries from leaving the platform as well.

Offers of investment, infrastructure finance, and COVID-19 vaccine supplies are the main tools in China’s arsenal. As the EU and non-EU participants in the 17+1 mechanism have differing needs and resources, China’s offer is relevant especially for the non-EU countries in the Western Balkans.

Already in 2020 during the first wave of the pandemic, Serbia was flooded by billboards proclaiming “thank you, brother Xi.” The campaign was a direct result of China’s mask diplomacy, which ushered in even more bizarre images, like that of the Serbian President Alexander Vučić kissing the Chinese flag during the ceremony welcoming the arrival of Chinese protective equipment. A steady supply of vaccines only furthered China’s goodwill in the country.

As for Chinese investment and infrastructure financing, the EU’s cumbersome response to Montenegro’s plea for aid in repaying Chinese loans helps to solidify China’s image as a viable alternative to the region’s integration in the EU.

To overcome these blunders, the EU needs to approach the Western Balkans with a clear strategy in mind. A strategy that is based around offering a clear path to membership for the states (provided they comply with the Copenhagen criteria) and countering the advances of rival authoritarian powers, whose inroads undermine the prospects of a future EU integration for the regional countries. As the EU already provides the region with much more money than China, it needs to invest in its visibility, as well as to explore redirecting a portion of the funds towards infrastructure construction.

Without a viable alternative, there is a low chance that Western Balkans will emulate the action taken by Lithuania and China will remain a key player in the region regardless.

Written by

Matej Šimalčík

MatejSimalcikMatej Šimalčík is Executive Director of the Central European Institute of Asian Studies, a think tank based in Slovakia, and a European China Policy Fellow at MERICS. He is a member of MapInfluenCE, a regional initiative aimed at monitoring China’s economic and political influence in Central Europe, where he acts as an analyst for Slovakia.