Protests in Serbia are provoking rarely seen responses from the government in Belgrade.

Faced with widespread unrest and demonstrations in the streets, the Serbian government recently withdrew Draft Amendments to the Law on Expropriation. This marked only the second time the Serbian president had withheld his signature from a law previously adopted by the National Assembly due to public pressure.

Yet, this is not the only aspect of recent developments with little to no precedent. Never before has a single project attracted as much attention as the Rio Tinto lithium extraction project planned in western Serbia.

The dissatisfaction of the general public has escalated in recent protests, making it clear that a large number of citizens are not willing to support the project, regardless of governmental proclamations about national interest. Therefore, when the National Assembly adopted amendments to the Law on Expropriation, the citizenry revolted, feeling the interest of the investor was put above the interest of the nation.

This level of outcry is instructive.

Although the protests are primarily driven by resistance to one particular project, public perception of the problem is much broader. Serbia is a country in which citizens see themselves as only silent observers that cannot effectively influence strategic decision-making on the use of public and natural resources. Therefore, it is relatively simple for the government to impose a unilaterally determined national interest for almost any project.

Needless to say, this dynamic can create a myriad of problems, as protests are making abundantly clear.

Defining National Interest

While the recent protests have been motivated mostly by environmental concerns, they have also put a spotlight on the poor management of the foreign investment policy. This is perhaps best exemplified by the fact that natural resources are “gifted” to foreign investors. To attract foreign investments, the Serbian Government often declares projects to be of national interest. However, in most cases, the public has no access to government decisions on this matter. In effect, laws are being applied flexibly and selectively to certain foreign investors.

The Amendments to the Law on Expropriation envisaged that the public interest may be determined for the implementation of construction projects of importance to the Republic of Serbia, in case those projects are implemented on the basis of an international agreement.

However, there are no explicit criteria set to determine whether an agreement-based project is in the public interest. As such, excessively wide discretionary powers are available to the government. In essence, the government could practically declare the public interest solely based upon fulfilling a single condition – that a certain international agreement has been signed, which would later be the basis for the expropriation of private property.

Even still, it is important to recognize that the absence of those provisions in the legal documents has not been an obstacle for privileged foreign investors in the past. The latest efforts are therefore basically just an attempt to fit an already established practice into legal frameworks. The standardization of these practices will likely make it even easier for certain foreign investors to present their activities as in line with the overall public interest.

In addition, competition and public procurement regulations are often relativized by passing special procedure laws. These laws enable the government to directly appoint a contractor for the implementation of a certain project. Moreover, it seems to be the case that the bigger the investment, the more opaque its terms. As a result, these larger projects often only attract public attention in later phases and can no longer be shrouded in secrecy. At this point, unfortunately, it is no longer a matter of prevention, but remediation.

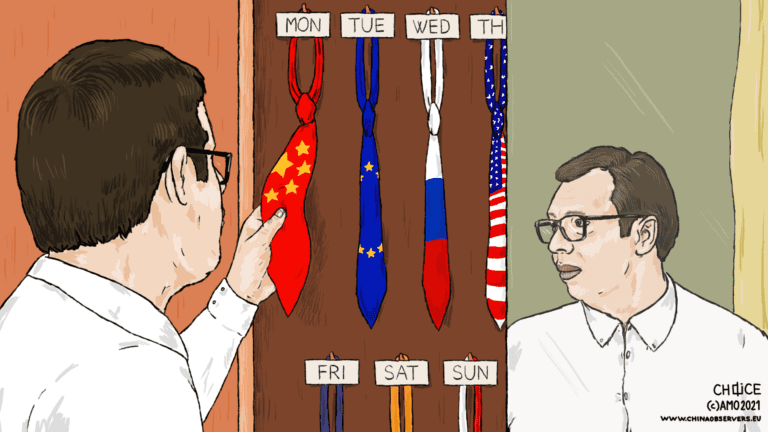

Favoring China

While the investment environment is accommodating the interests of many different foreign entities, the public authorities have proven to be particularly lenient in cases when the projects are implemented by Chinese investors. These have, through the years, benefited the most from a corrupt regime driven by private interests and have shielded the details of their projects by severely contravening transparency principles.

Chinese projects generally conform to a set pattern. Firstly, the parties sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in which there is often a very clear unequal redistribution of rights. One party promises to fulfill certain obligations (the government) and another only expresses its willingness to invest, provide funding, employ a certain number of locals, etc. (the investor).

Following the memorandum singing, there is always some level of state aid involved. The Renewables and Environmental Regulatory Institute (RERI) conducted an analysis of the state aid granted to the Linglong Tire Company, one of the world’s largest tire manufacturers with a turnover in 2018 of € 1.99 billion, employing over 16,000 people, investing in the construction of a tire factory in Serbia. Announced as the biggest investment in the country, Linglong received state aid in the amount of €75 million accompanied by 96 hectares of agricultural land as a gift to the investor, which brought the total estimated amount of state aid to €83 million.

RERI found the state aid unlawful due to numerous reasons: the competent authorities failed to declare that on top of the aid and land donation, the state awarded additional benefits to Linglong through long-term corporate tax holidays and duty-free import schemes. Moreover, Linglong received indirect state aid in the form of the development of infrastructure dedicated to the project through public resources. In effect, the total aid is likely to have exceeded the maximum aid allowed to large investment projects.

Circumventing the Law

Excessive state aid is but one of the troubling issues. In many cases, by avoiding proper impact assessment, projects with potentially harmful effects on the environment have been allowed to be carried out without hurdles.

Per Serbian legislation, before beginning construction works, the investor needs to conduct an environmental impact assessment for certain projects that may have adverse environmental impacts. Considering the fact that China is heavily investing in so-called ‘dirty industries’, this step is almost always necessary during project implementation. However, in practice, many projects fall short of standards.

In some cases, investors were in such a state of urgency that they “did not even have time” to apply for a construction permit.

According to Serbian legislation, construction without a construction permit is a crime and is punishable by imprisonment of six months to five years and a fine. That is why RERI initiated three criminal procedures against those responsible in Serbia Zijin Bor Copper and Linglong International Europe Ltd. for performing construction works without a construction permit.

In Bor, where Zijin is operating, RERI noticed that there are some facilities where construction has not only just begun but has progressed significantly. If the company followed existing regulations, by now they probably could have regularly applied for an operating permit. Proving that the law does not apply to everyone equally, the Serbian minister of environmental protection visited these illegally constructed facilities with journalists and publicly praised the progress of works.

It appears that some Chinese investors are using the ‘salami slicing’ method, dividing a single project into multiple separate projects. Via this method, those entities can avoid the environmental impact assessment of the project as a whole.

An example is the actions of Linglong, which divided its project into four phases.

Firstly, the firm constructed a fence around its factory without an impact assessment, then constructed auxiliary objects such as a parking lot, a restaurant, and more without conducting any environmental impact assessments of the burgeoning building projects outside the actual factory. Finally, Linglong artificially divided the factory itself into two parts, presenting them as separate projects. This is a crucial workaround, as if these projects were assessed as a single project, the determining environmental impacts would inevitably be larger, likely creating challenges in the project’s procession.

At the 26th annual summit of the Conference of the Parties, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić used the opportunity to praise the green investments of the Chinese companies HBIS Group Serbia Iron & Steel and Serbia Zijin Copper. This could not be more removed from the reality on the ground. In Bor, the concentration of sulfur dioxide dangerous to human health was recorded 25 times during 2020. In the same period, the concentration of heavy metals such as arsenic was almost 50 times higher than the target value. Radinac village, located near the iron factory operated by HBIS, was found to be the place with the longest period of air pollution in 2020 – excessive pollution was recorded on 148 days.

The lack of law enforcement is particularly noticeable in the absence of proper inspection surveillance. The state authorities choose to use a more tolerant treatment towards investors instead of available legal mechanisms, such as criminal charges, which can and should result in stricter sanctions for investors breaching environmental regulations.

This practically enables privileged companies to proceed with their business as usual, paying only symbolic fines. Still, business as usual comes with great expenses as there is a higher risk of mortality in Bor than in any other part of the country, per official data.

The Way Forward

Naturally, China seeks to secure the most favorable business conditions for its companies. In achieving that goal, they, understandably, attempt to reduce investment costs by requesting a variety of benefits from the national authorities. The issue is in the Serbian government’s near consummate acquiescence to these requests.

After all, the role of the Serbian government is to step up and protect its citizens, rather than find ways to accommodate investors’ interests.

On the other hand, without concrete EU support, changes to this dynamic should not be expected. The EU provides financial and technical support to Serbia, but it errs on the side of enforcing accountability and anti-corruption mechanisms, creating significant tradeoffs for governments like Serbia’s.

At the same time, the European Parliament has tried to call more attention to the issue. Last December, MEPs adopted a resolution on forced labor in the Linglong factory and environmental protests in Serbia, which, among other things pointed to “the serious problems with corruption and the rule of law in the environment area, over the general lack of transparency and environmental and social impact assessments of infrastructure projects, including from Chinese investments and loans as well as from multinational companies such as Rio Tinto.”

Although Serbia pledged to align its goals with the EU, the sustainable development agenda is not recognized in Serbia as a developmental paradigm. In Serbia, the long-term campaign professing that economic development is a priority by all costs has clearly won out.

Moreover, the Serbian general population is not sufficiently informed on the scope of environmental problems, abetting the ‘economic growth at all costs’ mantra. Only recently has there been a public awakening, with the Serbian public starting to address issues of environmental justice and demanding action.

Still, public pressure, while important, is only a first step. Overcoming environmental challenges requires an institutional change in government policies, economic strategy, and understanding of the rule of law.

On all of these points, there is still a long way forward yet.

Written by

Hristina Vojvodić

Hristina Vojvodić is a legal expert in the area of energy and environmental law at the Renewables and Environmental Regulatory Institute in Belgrade. She is also currently completing her PhD at University of Belgrade.