Dancing Lions: China’s Influence Campaigns Target Influencers

This article is part of a newly launched section of CHOICE dedicated to in-depth investigations and personal insights that illuminate the lesser-known dimensions of Chinese influence in Central and Eastern Europe. In this space, we invite journalists, influencers, researchers, civil society actors, and others with first-hand experience to share stories that we believe decision-makers cannot afford to ignore. From covert media campaigns to subtle outreach tactics, this series shines a light on the informal tools and overlooked actors shaping perceptions of China in our region.

While attention in Central Europe has often centered on Russian propaganda, China has been quietly cultivating its own influence operations through unexpected channels – from Czech radio stations to TikTok influencers and all-expenses-paid trips to China. These efforts reveal a growing sophistication in Beijing’s strategy to shape perceptions abroad, leveraging entertainment, travel, and digital culture to mask deeper political objectives. What appears at first glance to be harmless cultural exchange may, in fact, form part of a broader, state-driven influence campaign with far-reaching implications for public discourse and (social) media integrity in the Czech Republic and beyond.

I’m Milan, a travel-focused content creator for Refresher and an Instagram influencer. In January 2025, I received an email from an agency called China Seeing, offering a free “exclusive holiday” in China – flights, visas, accommodation, and a tailored itinerary, all covered. What caught my attention was their insistence that I wouldn’t need to post anything on my own social media; the material was intended solely for Chinese audiences. The only expectation was participation in brief promotional videos for a destination marketing organization they referred to as “Experience China,” which appears to have no verifiable public presence.

Curious, I continued the conversation and floated a filming fee of €2,000 per day. I received a swift and polite response acknowledging the rate as above average but affirming a willingness to negotiate in person. Although the meeting never took place and the communication ceased, it became clear that I had been approached as part of a coordinated and well-prepared campaign. The website for China Seeing was registered only in November 2024, and according to public domain data, it was filed under the name Josef Novák – essentially the Czech equivalent of John Doe – raising further questions about the company’s legitimacy and its ties to Chinese state interests.

From Radio Waves to Social Feeds

This offer was not an isolated case. Friends of mine – also influencers – received similar proposals but declined. Others may have accepted under the condition that they remain silent about it. Since neither of these campaigns required participants to post content publicly, it is difficult to estimate how many of such collaborations actually took place – or are still ongoing – without public knowledge.

Beyond influencers, China’s covert propaganda has infiltrated traditional Czech media. Between 2019 and 2023, the show “Barevný svět” aired up to six times a week on Radio HEY. While it appeared to be a travel program, analysis by China analyst Ivana Karásková revealed it was produced in partnership with China Radio International (CRI), a state outlet under the Chinese Communist Party’s control. The program portrayed China exclusively in a positive light, referred to Taiwan as “the largest island belonging to China,” and promoted Tibet’s inclusion as a rightful part of the country. The broadcast was discontinued only after Karásková’s findings were published.

Print and television media have not been immune either. After Chinese conglomerate CEFC entered Empresa Media, negative or even neutral reporting on China disappeared from the media group’s major outlets such as Týden and TV Barrandov. In 2019, the Czech daily Právo published an eight-page insert celebrating 70 years of Czech-China relations. Although marked as commercial content in fine print, the pages were authored by Czech journalists – blurring the lines between editorial and advertorial.

TikTok campaigns have also been rolled out in the Czech Republic with increasing subtlety. In late 2022, Czech influencers Dominique Alagia and Lukáš Tůma participated in a sponsored trend featuring a cartoon lion – referencing the Czech national symbol – created by CRI. The influencers were instructed to dance and tag accounts operated by CRI employees using Czech first names “Pepa” Zhang and “Lada” Wang.

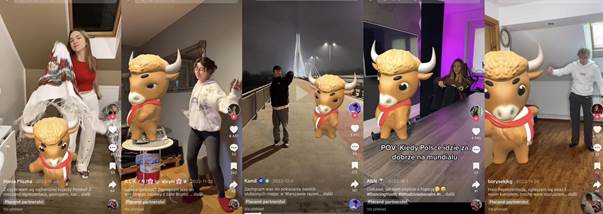

Although not all Czech influencers explicitly disclosed the paid nature of the collaboration, parallel campaigns were launched in Poland and Greece, adapting national symbols to better resonate with local audiences – a young bull (ciołek) in Poland and an owl, a classical symbol of wisdom, in Greece. In both cases, European influencers were contacted to collaborate with TikTok accounts run by Chinese individuals fluent in local languages, who produce content targeted at European audiences. The goal was to boost the engagement of these Chinese influencers operating in Europe.

In Poland, a Chinese woman fluent in Polish, Oliwia Waskocha, coordinated the campaign in November 2022, involving a large number of influencers; collectively, these Polish influencers currently amass nearly 7 million followers on TikTok alone. In Greece, a Chinese woman operating under the handle @mariannalee_ (with 81,400 TikTok followers) spearheaded a comparable campaign, using dance performances featuring an owl to symbolically connect with Greek cultural heritage.

Interestingly, both the Polish and Greek campaigns were explicitly labelled as paid collaborations, resulting in greater transparency compared to the Czech cases. This distinction could indicate a more cautious approach in Poland and Greece, possibly reflecting either stricter local regulations on advertising transparency or a greater sensitivity among influencers to issues of authenticity and public trust.

The Notorious Case of Jan Michálek

In 2023, the Czech campaign evolved. A group of influencers – including Dominique Alagia, Jan Michálek, Samuel Samake, Hanka Gelnárová, Vít Vencl, Tran Kim Ly and Lukáš Tůma – began posting longer “reaction” videos to Chinese cultural content originally published by the CRI employees Pepa and Lada. These often featured lifestyle footage – skincare routines, meals, or casual commentary – interwoven with glowing references to Chinese ethnic minorities, such as the Miao. The tone remained overwhelmingly positive. Such portrayals aim to present China as both harmonious and multicultural, diverting attention from issues and controversies that the international public associates with the Chinese regime.

One of these influencers – Jan Michálek – even travelled to China, a trip fully funded by Chinese entities, which he confirmed in a 2024 podcast. A promotional video published by Pepa Zhang’s official Facebook account shows Michálek enjoying Xinjiang’s landscapes and cultural festivals, portraying a region better known internationally for its human rights controversies as an idyllic travel destination. Both Pepa and Lada are featured singing with their Czech guest, suggesting not just casual exchange but orchestrated cultural diplomacy.

Behind the Free Trips and Hidden Deals

The term “white monkey,” often used pejoratively in some Asian contexts, refers to Westerners hired to lend prestige to events or promotional content. Though problematic, it may describe the underlying logic of these Chinese-sponsored influencer trips: showcasing foreign admiration to boost China’s image among its own citizens. By omitting political issues, these campaigns present China as modern, friendly, and culturally rich – ideal for soft power projection.

My own brush with this campaign ended in silence, but the story points to a broader and coordinated strategy. As China’s influence becomes more diffuse, it also becomes more difficult to detect. The challenge is not only in identifying overt propaganda, but in recognizing when soft influence masquerades as harmless content.

TikTok represents an ideal platform for Chinese state-linked actors to disseminate promotional content. Influencers on the app are not only accustomed to paid collaborations, but they also command the attention of vast, often young, audiences who place a high degree of trust in their recommendations. These creators offer a ready-made channel for subtle messaging that bypasses traditional media scrutiny. Crucially, TikTok remains largely unmonitored by governmental or civil society institutions that might otherwise flag, contextualize, or push back against such content. This vacuum creates fertile ground for influence operations to take root and spread, often unnoticed, in the feeds of millions.

Update (May 18, 2025): It has since been revealed that “China Seeing” was, in fact, a prank orchestrated by Czech comedian Martin Mikyska, known online as Mikýř. The fictitious company invited 40 Czech influencers on what was presented as a trip to China. However, this does not change the findings of my investigation, which began as a result of this incident and uncovered Czech influencers who were paid to promote the profiles of “Lada” and “Pepa” – employees of China Radio International.

Written by

Milan Dobrovolný

MilanDobrovolnyMilan Dobrovolný is a Czech travel influencer and content creator for Refresher.