This article was originally published at China Foresight, LSE IDEAS, and is republished here as part of a partnership between CHOICE and China Foresight.

Ukrainian military successes in the second half of 2022 have not only precipitated a crisis in Russia but caused many experts to wonder whether Xi is re-evaluating his relationship with Putin. A study of the available evidence would indicate at the time of writing that those looking for a deep crisis in the Xi-Putin relationship are likely to be disappointed. China and Russia will thus remain together, united by what they see as a hostile liberal West led by the United States opposed to their interests in both Europe and East Asia.

Many years ago the social theorist Nassim Nicholas Taleb advanced what then seemed the novel idea that the big tipping-point moments in modern international history are more often than not those the world least expects. He termed these events “Black Swan”. By any measure, what Putin decided to do on February 24 looks like a classic example of a “Black Swan.” Few after all saw the invasion coming; hardly any analysts, except the intelligence services of the United States and the UK, predicted it would happen; and its global consequences have been immense.

But Putin has to have been shocked too. Aided and abetted by Russia’s military ineptitude, armed by the Americans and its NATO allies, and effectively led by a former comedian turned war leader while showing enormous resolve of its own, Ukraine has not only surprised some of its allies who calculated it might go under in a few short weeks, but also delivered a very real shock to the Russian military itself. Indeed, with the costs of the war escalating in terms of casualties (an estimated 60,000 by August) and sanctions shutting the door on a wide range of technologies and goods from the West, by late 2022 Russia found itself in a very different place to where it thought it might have been a few short months before.

Putin of course still has options. His position is weak but not yet fatal. Nonetheless, with GDP falling by around 6 percent, tens of thousands of Russians now leaving the country to avoid being called up, resistance to the war growing in the county’s more marginal regions, and Putin now under attack from those on his nationalist right calling for an escalation of the war, Russia’s future looks to be anything but certain. As the great strategist Clausewitz warned over a century ago, launching a war is easy: bringing it to a successful conclusion, most difficult.

But Russia has only experienced the war at one stage removed. The same can hardly be said of Ukraine. Here the consequences have been nothing short of catastrophic with 7 million displaced internally, 6 million forced to become refugees, the death and injury of thousands of civilians, the destruction of schools, bridges, hospitals and other infrastructure, a number of once thriving towns reduced to rubble, strong evidence of the use of torture according to the UN, an untold number of Ukrainians now being held incommunicado in Russia, and if and when the war ends, a massive reconstruction bill of close to $400bn to help put Ukraine back on its feet again. Nothing like this has been witnessed in over a generation, except perhaps in Syria from which Russia appears to have drawn significant military lessons which have been mercilessly applied to the cities and towns of Ukraine itself.

From Winner to Loser?

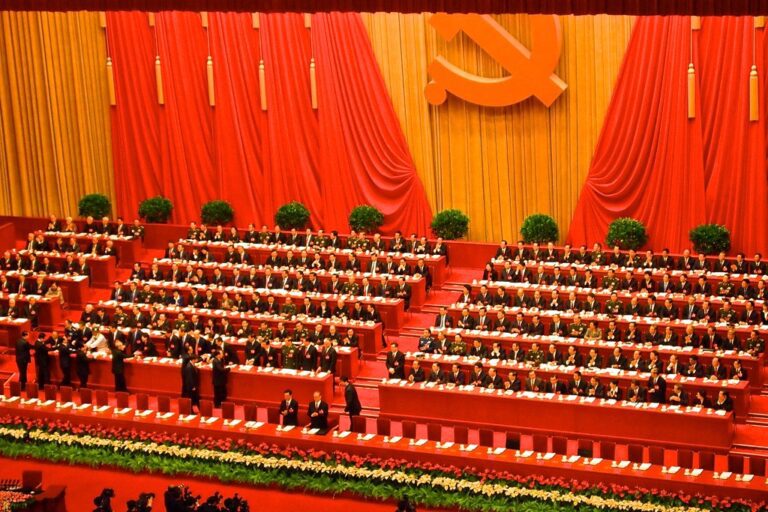

But what role have other actors played in this ongoing tragedy? Putin of course views the war almost completely through an extreme nationalist lens in which the United States using NATO – an organization with its own “imperial ambitions” he claims – is engaged in a plot whose goal is nothing less than the destruction of Russia itself. But there has been another, very different kind of player involved in this ‘great game’: namely The People’s Republic of China, once the USSR’s bitterest enemy now locked into a very special relationship with its old foe, one which it formalized in grand style in a lengthy 5000 word communique issued in February which declared – or more precisely repeated what China’s Vice Foreign Minister had said the previous December – that there were “no limits” and “no forbidden zone to cooperation.”

No doubt historians will forever be debating whether there was any kind of connection between a statement published by Putin and Xi on February 4 and a war launched twenty days later. But as one of the more astute observers of the Chinese scene has pointed out, with over 150,000 Russian troops massed on Ukraine’s border at the time and US officials repeatedly warning Beijing that a war was almost imminent, Xi could not have been unaware that something was about to happen. Later, some eminent Chinese historians opposed to the war claimed Xi had been deceived by Putin. Possibly so. But it is equally plausible that simply having China standing behind him, quite literally holding his coat without getting into the ring itself, may have emboldened Putin to act in the way in which he finally did on February 24th.

But where does this leave China now that the war has turned from being a short one – which presumably it was probably hoping for back in February – into a decidedly long one which in spite of its less than credible claim of not being a “party to the war,” is damaging its reputation, causing some unease at home, contradicting its own principle of non-intervention and generating all sorts of problems with its biggest trading partner, the European Union. China has never had qualms about supporting some fairly unsavory regimes. But supporting Putin as he continues his costly and deadly war of attrition against Ukraine is something else altogether. In February Xi might have thought he was backing a winner; now it seems he may have tied his fate to a possible loser.

Xi in a Corner?

How Xi himself assessed the situation, as military stalemate over summer very quickly turned into Ukrainian military success by September, is almost impossible to know. But his public stance at least exuded one of studied diplomatic serenity, in large part presumably (though we can never know for sure) because Putin had reassured him that he still had a strategy that would bring the war to a conclusion without giving the West the satisfaction of knowing that its Ukrainian ally had come anywhere close to winning. The strategy moreover very quickly began to take shape with Russia first making sure that oil prices did not sink too low (hence the deal with Saudi Arabia in early October) and then escalating its attacks on critical infrastructure across the whole of Ukraine. To this particular combination, Putin then added nuclear blackmail, further territorial annexations, the calling up of 300,000 reservists, causing as much economic pain as possible to Ukraine’s supporters in the West by cutting off all gas supplies, and perhaps crucially, keeping its one true friend China on side.

Indeed, in what looked like a piece of well-rehearsed diplomatic theatre Putin even conceded in September that Xi might have some “questions and concerns” that needed to be addressed. What these were exactly was never made clear in his meeting with the Chinese leader, though he did allude to the fact that these had been “spoken” about “before,” the clear implication being that this was hardly the first time, and possibly not the last, when such issues had been discussed between the two.

Even raising the issue in such a public fashion was not without significance. In fact, so significant did it seem to be that the official press back in China did not even report what Putin had said. In the West, however, his words set off a wave of highly speculative commentary, even leading some pundits to conclude that a potentially serious divide might now be opening up between the two countries. One foreign policy magazine even ran with the dramatic headline question as to whether or not China was now “breaking” with Russia. Another well-known writer on foreign affairs then suggested that Xi might now be beginning to regret “embracing his Russian counterpart.”

There were even rumors coming out of China that something might be up. Thus even though the official press did not report what Putin had said, many on Chinese social media did. The earlier demotion of Foreign Vice-Minister Le Yucheng (one of China’s leading Russian experts who had in April called upon both sides “to deepen” their cooperation) was seen as perhaps another sign that Beijing’s relationship with Moscow was coming under increasing scrutiny. We were even informed that whereas in the past Chinese public opinion had been on the side of Russia, ordinary Chinese were now beginning to change their minds. Meanwhile, a number of Western journalists ‘in the know’ also started picking up information from unnamed sources that senior people back in Beijing were becoming increasingly frustrated with Russia’s progress in the war. At long last, it seemed as if all those in the West who had been looking for some good news after many months of bad news now had something to cling on to: a possible crack in the solid edifice known as the Sino-Russian axis.

Stand by Your Man

All these various straws in the wind may have indicated some degree of unease in Beijing. However, there is little to suggest that serious cracks were opening up in the Xi-Putin relationship. Private complaints there may well have been. Even Xi in private might have been concerned. But if he was, there was no indication in his public pronouncements that he was about to rethink policy towards Russia. Indeed, he did not even mention Ukraine in his various discussions with Putin. What he did talk about however was Putin’s continued and most welcome support for China over Taiwan and Beijing’s “One China” principle. He then called upon the two nations to strengthen their cooperation across a number of areas of common economic interest and security while coordinating their work together in international bodies such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the BRICS. Finally, as if to make his position clear, he confirmed that China was as ever ready to work with Russia in order for both to achieve their respective “core interests” together. If Xi was either backing away from Putin, or seeking to demonstrate his displeasure with his old and loyal friend, then this was a very odd way of doing so.

But it was what was happening outside the conference room as much as what Xi was saying to Putin inside it, which best indicated the direction of travel. Here all the signs pointed not to a fraying of the friendship but rather to a reaffirmation of it, although increasingly on Chinese terms. Thus only a few days before Putin and Xi met, the two countries held yet another military exercise, a strong indication that security cooperation between Russia and China was continuing to grow. Along with a number of other countries in the wider Eurasian region, Russia and China then attended the most important trade event in the Far East, significantly held under the banner title of On the Path to a Multipolar World. Then, as if to confirm the growing importance of the economic links between the two countries, September figures pointed to yet another sharp rise in their two-way trade.

There were other important indicators too of how close the two countries remained – one of the more significant perhaps being the visit by senior Chinese official Li Zhanshu to Moscow in early September, where not only did he say that China “fully” understood why Russia had taken the necessary measures it had in Ukraine – Russia had been put in an “impossible situation” he claimed – but went to call upon both countries to fight together to combat any “external interference.” A little later that month Putin’s national security chief, the immensely influential Nikolai Patrushev, also visited China on a two day visit, where aside from denouncing the West for promoting ‘bogus’ values called upon both sides to further strengthen what he called their “comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation.” Apparently his meeting with Guo Shengkun – China’s top security chief who was reported to have called for “reform through education” in Xinjiang – must have gone well. Indeed, Patrushev’s office later issued a statement after the talks noting that both parties had agreed to “expand information exchanges on countering extremism and foreign attempts to undermine constitutional order of both countries.”

From Color Revolutions to Taiwan

Nor was there any sign that the two were beginning to move apart on other “core interests.” One of these was their very strong desire to prevent uncontrolled political change from below. It was perhaps significant therefore that in a speech Xi delivered at the 16th SCO summit in the Uzbek capital of Samarkand extolling what he termed the ‘Shanghai Spirit’, that he went on to warn fellow rulers about the danger posed by “color revolutions.” More or less repeating what Putin had talked about earlier in the year of Russia’s “near abroad” being threatened by those seeking to “rock the boat,” Xi said there was an equally great danger that such upheavals would be exploited by “external forces” seeking to do the same in Central Asia. It was never made clear explicitly who these external forces might be. But it was fairly obvious to which country he might be referring when he went on to denounce all those still adhering to a “Cold War mentality” and “bloc politics” who with others were continuing to cause “uncertainty in our world today.”

A far less subtle attack on the United States also figured heavily at a press conference hosted by the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs a few days later in Beijing. Here, Zhao Lijian – never known for understatement when it came to Washington – attacked the United States for all manner of political misdemeanors. Nor were the perhaps less ‘wolf warrior’ like comments made by another official only a few days later, any the less critical of the United States. The list of Washington’s policy errors was almost endless according to Wang Wenbin, but by far the most unacceptable he insisted was its continuing interference into Chinese internal affairs by forever getting involved in Taiwan, which some Americans were now even calling a ‘country’.

Unsurprisingly, Taiwan also figured in a speech made by Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov. Delivered at a keynote session in the UN, the experienced diplomat who had by now become the voice of Russia insisted that the US was – as in Ukraine itself – “playing with fire” and stoking up unnecessary tensions which could very easily end very badly indeed. The fact that a leading Russian spokesperson was once again raising the issue in the midst of a war going on in Ukraine when Russia was looking for all the support it could get from China, was not without significance. Nor would it have gone unnoticed in Zhongnanhai where one suspects that Putin’s support for China on Taiwan almost certainly outweighed any “concerns” Xi may have had about Ukraine. Certainly, if as some in Beijing feared that Washington was slowly but surely beginning to recalibrate its ‘One China’ policy in the process of moving away from a policy of ‘strategic ambiguity’ to ‘strategic clarity’ regarding Taiwan, then Russia’s support was likely to be regarded as being of even greater importance.

Conclusion: Faustian Bargain

Russian setbacks in the “plains and river valleys of Donetsk” and elsewhere in Ukraine, were clearly not going to be enough to make Xi rethink his relationship with Putin. This did not mean that Beijing wanted to see the war in Ukraine continue indefinitely. Indeed, as if to prove how keen it was in promoting a peace process between Ukraine and Russia, it issued yet another plea – this time in association with India at the UN – calling on both Russia and Ukraine to “keep the crisis from spilling over.” However, as Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi noted in what was an otherwise emollient speech, until “a balanced, effective and sustainable security architecture” could be established that would address “the legitimate security concerns of all parties,” including by definition Russia – who had for years been opposed to NATO – then by implication there was minimal chance of the conflict in Ukraine coming to an end any time soon.

Nor did China seem much interested in discussing peace with the Ukrainian leadership himself. Indeed, when another Chinese spokesperson was asked by a correspondent when President Xi would actually be talking directly to President Zelensky to help bring about an end to hostilities, the decidedly non-committal (indeed completely irrelevant) response was that in the year before the conflict began economic relations between the two countries had been going from strength to strength. Moreover, when later pressed to talk about Russia’s military escalation, the response by one diplomat was not to talk about Russia but rather call upon all parties, including the one dropping bombs on Kyiv, to find a way of addressing their “differences” and engage in “dialogue and negotiation.”

It is true that the foreign ministers of both Ukraine and China did manage to meet on the ‘sidelines’ of the UN General Assembly in September. Remarkably though this was the first face-to-face encounter since the war had begun. Moreover, from what can be gleaned from official sources, China yet again said nothing directly about Russia’s attacks on Ukraine but a great deal about how much it respected Ukraine’s “sovereignty and territorial integrity.” Unfortunately, this diplomatic gesture did nothing to deter Putin from escalating the war and going on to sign ‘accession treaties’ in the Kremlin a week later formalizing Russia’s “illegal annexation of four occupied regions in Ukraine.”

Meanwhile, as China grappled with the delicate task of squaring the circle of formally proclaiming its support for Ukrainian sovereignty while promoting Russia’s view of the war (without of course getting involved in the conflict itself) the many battles for Ukraine fought on several fronts continued unabated. No doubt this placed China in an awkward position which could very easily become more awkward if Putin started to think seriously about deploying nuclear weapons, or if his position at home became increasingly untenable. Yet having made his own Faustian bargain with the Russian leader many years ago, there was, it seems, no turning back for Xi. Nor in many ways was there very much reason for him to do so given how dependent an increasingly isolated and sanctioned Russia was already becoming on China, by now the senior partner in an increasingly asymmetrical relationship.

But if Putin is locked into an unequal relationship with his Chinese counterpart, Xi is in his own way trapped too. Putin, it was once claimed, said he could not afford to lose the war in Ukraine; one suspects Xi must felt the same about Putin. Only time would tell how things would unfold. But for the foreseeable future at least, there was every indication that the two would continue to row in the same direction, not just because they are trying to navigate their way towards the same point on the international horizon – one in which the United States and the West will no longer be defining the global agenda – but because if they didn’t continue doing so, then the boat in which they are traveling might well be swamped by the rough and turbulent waters that lay all around it.

Some interesting times thus lay ahead for what until now had proven to be a remarkably solid relationship, one that was certainly proving to be a lot more durable than the one which some experts had been talking about in the months and years before the war. Like any relationship, even one without limits this one was bound to have boundaries. But as Russia’s ‘special’ and very destructive ‘military operation’ in Ukraine continued, it was increasingly difficult to know how far those boundaries extended and for how long they would remain in place.

Written by

Michael Cox

Professor Michael Cox was a Founding Director of LSE IDEAS and is now Emeritus Professor of International Relations. He has served as Senior Fellow at the Nobel Institute in Oslo and is now a visiting professor at the Catholic University of Milan.