China at COP27: “Loss and Damage” and Fossil Fuels Take Center Stage

As the largest greenhouse gas emitter with the second highest cumulative emissions, China was an essential player in key negotiations at this year’s COP27 concerning the climate impact compensation and emissions reductions. China will need to step up to phase-out fossil fuels, otherwise it will likely also face increasing calls to take responsibility for its share of the climate crisis and pay up for loss and damage.

The recently concluded climate Conference of Parties (COP) 27 was held in a year when the impacts of the escalating climate crisis were increasingly felt around the world, from devastating floods in Pakistan and Nigeria, protracted drought in East Africa, and record summer heat waves in Europe and China.

The Emissions Gap Report 2022 published by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) shortly before COP27 meanwhile highlighted that policies currently in place could result in global temperatures rise of 2.8°C by 2100.

Accordingly, two primary issues discussed in Egypt’s Sharm El-Sheikh was the financing for Loss and Damage to compensate those losing lives and livelihoods to climate impacts, and the greenhouse gas emissions cuts and fossil fuels reductions needed to limit global warming.

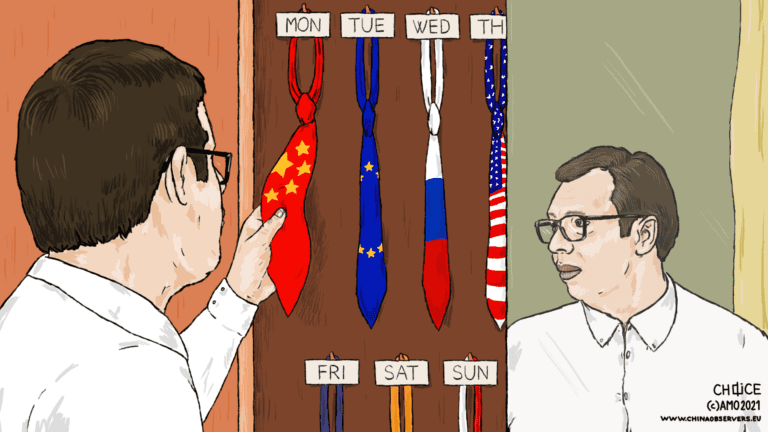

As a developing country that is also the world’s largest annual CO2 emitter (overtaking the USA in 2006), and second largest cumulative CO2 emitter (emissions since 1850), China was deeply involved and implicated in the negotiations at COP27. China’s actions will be crucial for resolving the climate crisis and it urgently needs to act on its responsibility.

The Difficult Birth of an Overdue Loss and Damage Fund

Developing countries, particularly those most vulnerable to climate impacts such as small island states, had championed the issue of Loss and Damage since 1991 when Vanuatu proposed an international insurance pool to compensate small island developing states for the impacts of sea-level rise. They argued that wealthy countries whose carbon emissions had historically contributed the most to climate change should compensate those who have contributed least to the problem yet are experiencing the worst impacts.

At COP26 in Glasgow in 2021, developing countries including China were unified in calling for the establishment of a Loss and Damage finance facility, a call ultimately blocked by developed countries on the last day of the conference. At the beginning of COP27, developing countries including China, supported by civil society allies, successfully pushed for the issue of Loss and Damage finance to be added to the official COP agenda. This was the first time in the history of climate COPs that Loss and Damage finance was adopted into the conference agenda.

Such a development was particularly timely as research from insurer Swiss Re had found that natural catastrophes in 2021 had resulted in economic losses of USD 270 billion. The extensive natural catastrophes in 2022 amplified by climate change likely resulted in even greater economic losses. Furthermore, climate impacts cause losses and damages beyond the economic sphere, and this was recognised in negotiating texts under the Loss and Damage finance agenda item at COP27.

Negotiations concerning loss and damage finance were intense at COP27. Developing countries including China were unified in their demand for the establishment of a Loss and Damage fund that would be paid for by developed countries. In the first week of negotiations, China’s special envoy for climate change Xie Zhenhua publicly backed the proposal and simultaneously insisted that China had no need to compensate others for Loss and Damage.

Developed countries, on the other hand, resisted the proposal for the fund over concerns it could open them up to liabilities for the impacts of historical emissions. They touted other proposals instead. Germany in its role as President of the G7 championed the Global Shield Against Climate Risk, which was also launched at this year’s COP. This is an insurance-based mechanism to mobilise finance against climate change-related disasters. While approximately $282.4 million was pledged by wealthy countries to support this initiative, the amounts raised are small compared to the scale of the losses and damages caused by climate impacts. For instance, this year’s catastrophic floods in Pakistan alone caused an estimated $30 billion of losses and damages. Developing countries were also concerned that an insurance-based mechanism would ultimately add further financial burdens in the form of insurance premiums that they could not afford.

At COP27, cracks appeared among the united front of developing countries with regards to Loss and Damage. For the first time, small island developing states publicly called on China and India to also pay for climate Loss and Damage, grouping them together with other major emitters. At the same time, the group of developed countries sought to capitalise on any perceived divisions among developing countries.

As the deadlocked negotiations drew towards their scheduled end, the EU reversed its stiff opposition towards the establishment of the fund, and put forth a proposal that would also include contributors from among the ranks of developing countries. The EU proposal turned the tables on developing countries, particularly China, with its high annual emissions, extensive cumulative emissions, and large GDP. The shift in the EU’s position spurred a final sprint of negotiations to secure a consensus agreement on the establishment of a Loss and Damage fund.

In the morning of 20 November 2022, two days after the scheduled end of COP27, a consensus agreement on creating the fund was finally achieved. The final consensus agreement left the details of the fund’s operationalisation to be hashed out by a Transitional Committee. The Committee would consider institutional arrangements and modalities for the new mechanism.

Significantly, the final agreement includes a recommendation for the Committee to consider identifying and expanding sources of funding. This potentially opens the way for China and other high emitting developing countries to face calls to also add their contribution

China already provides aid to countries who have suffered from climate impacts, such as the almost $90 million relief assistance in cash and kind from various Chinese sources committed to Pakistan as of October 2022. Such disaster relief aid, while welcome, pales in comparison to the scale of resources required by countries like Pakistan to recover from devastating climate impacts.

Going forward, Beijing is likely to face increasing pressure from both developed and developing countries to contribute towards the new multilateral Loss and Damage fund. China will probably resist such calls on the grounds that it too is a developing country that has experienced climate impacts. China will likely also continue to highlight that developed countries have yet to honour their pledge made in Copenhagen in 2009 to provide $100 billion in climate finance annually to developing countries.

Furthermore, while China’s cumulative CO2 emissions are large, they only started to spike in the latter half of the 20th century, particularly after the commencement of economic reforms in the 1980s. This is unlike the cumulative emissions of countries such as the United States and Germany that started to spike from the Industrial Revolution of the mid-19th century onwards. China therefore could be said to bear less historical responsibility for the climate impacts currently ravaging countries like Pakistan and therefore potentially less liable to have to pay for climate Loss and Damage.

Missed Chance to Progress Towards Phase-Out of Fossil Fuels

While a moral victory on Loss and Damage was achieved at COP27, the conference outcome ultimately failed to make progress on addressing the root cause of the climate crisis – reducing carbon emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels.

Last year’s COP26 Glasgow Pact was historic in being the first in the series of climate conference outcome decisions to mention coal and fossil fuel subsidies. Still, on the final day of COP26, China and India, speaking on behalf of a group of developing countries, watered down the Glasgow Pact language concerning coal from “phase-out” to “phase-down.”

At COP27, there were hopes to build on the landmark Glasgow Pact and make progress towards phasing out fossil fuels. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has made clear that CO2 emissions must decline by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net zero around 2050 in order to limit global warming to 1.5°C with limited to no overshoots in order to prevent the worst catastrophic impacts of climate change. The IPCC has also shown that rapid and far-reaching transitions in energy, land, urban and infrastructure (including transport and buildings), and industrial systems are needed to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

China came to COP27 having experienced a record CO2 emissions reduction of 8 percent in the second quarter of 2022. This reduction of 230 million tonnes of CO2 emissions is the largest in China in at least a decade. China’s second quarter 2022 CO2 emissions reductions however occurred amid a context of its ongoing real-estate crisis, and the economic effects of the zero Covid policy, that resulted in weak growth in electricity demand.

There was, however, simultaneously also strong growth in renewable output in China. As of the end of June 2022, China’s wind power generation capacity was 340 million kilowatts, a year-on-year increase of 17.2 percent, and its solar power generation capacity was 340 million kilowatts, a year-on-year increase of 25.8 percent.

It is noteworthy that during the COP27 conference, the previous alignment between China and India on fossil fuels began to diverge. India notably called for the phase-down of all fossil fuels. China however did not follow India’s rhetorical lead despite its domestic progress on renewable energy capacity.

The COP27 outcome thus ultimately merely reproduced language from the Glasgow Pact, despite calls by an increasing number of countries, including historic oil producers like Norway, for the phase-out of fossil fuels. Oil-producing states allied to host country Egypt in the end blocked an ambitious outcome decision on fossil fuels.

Time and Opportunity for China To Step Up

While China was not a major stumbling block at COP27 concerning progress on fossil fuels, the CO2 emissions reductions needed to limit global warming to 1.5°C can only happen if China, the world’s largest emitter does its part.

In 2021, China still derived 82.72 percent of its primary energy from fossil fuels (coal 54.66 percent, oil 19.41 percent, and gas 8.65 percent). China’s coal usage had trended downwards in recent years, although China boosted coal production and consumption in 2022 to ensure energy security after experiencing two waves of disruptive electricity shortages in 2021. At the same time, China’s usage of gas is on an upward trend. Immediately after the conclusion of COP27, China concluded a 27-year gas supply deal with Qatar. This does not augur well for the global phase-out of fossil fuels that is necessary to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

Furthermore, as China’s economic strength and influence has grown, it, like other major emitters, also contributes to the climate crisis via the financing of fossil fuels projects abroad. As of September 2022, estimated emissions for currently operating China-financed power plants overseas total 245 million tons of CO2 per year, an amount approximately equalling the annual energy-related CO2 emissions of Spain or Thailand.

There are some positive developments such as China’s pledge in 2021 to stop building overseas coal power plants. Since China’s pledge, 26 overseas coal plant projects (21 GW) were cancelled, avoiding the addition of an estimated 85 million tonnes of CO2 per year. Some caveats concerning these cancelled overseas coal plants are that the majority of the cancellations were initiated by host countries, while others were cancelled as a result of poor project economics, lengthy legal challenges and local resistance, or delays in securing financing or permits.

Despite the avoided emissions from the cancelled coal plants, the potential added emissions from China-financed overseas power plants remains elevated. If China-financed fossil fuel based power plants that are currently under construction and in planning overseas come online, they will add another estimated 82 million tonnes and 23 million tonnes of annual CO2 emissions, respectively.

The outcome of COP27 with regards to fossil fuels lacked ambition and leaves the world still on track towards catastrophic levels of global warming. However, China need not be limited by the multilateral process and can demonstrate leadership in the fight against climate change. China is already a world leader in renewable energy, with its installed solar and wind energy capacity currently accounting for 35-40 percent of the global total. China is also financing renewable energy projects abroad. Solar and wind energy plants currently constitute 12 percent of the capacity of the overseas power units financed via Chinese investment and loans.

China can and should work towards phasing out all fossil fuels domestically and support the energy transition globally. Otherwise, if China’s cumulative carbon emissions continue to increase, and it continues to support fossil fuel expansion and use abroad, it may find itself increasingly confronted by vulnerable countries already experiencing the worst climate impacts to take responsibility for its share of the climate crisis and pay up for climate Loss and Damage, which will only increase with worsening climate impacts.

Written by

Julian Theseira

Julian Theseira coordinates the Global Stocktake (GST) Working Group of the Climate Action Network (CAN). He is also a research assistant at the Association for International Affairs (AMO), in Prague, Czech Republic, and Erasmus Mundus scholar in the European Politics and Society (EPS) Master program at Charles University, Prague, and Jagiellonian University, Krakow.