Beijing Olympics Row Reveals Cracks in the Czech China Policy

The new Czech government under Prime Minister Petr Fiala, just inaugurated in December, promised “a change people can believe in.” Among these expected changes, foreign policy is one of the most prominent areas due for a shakeup.

The government has pledged a return to Havelian foreign policy including a revision of ties with China. However, a controversy over the Beijing Olympics shows that the government’s efforts might be undermined by President Miloš Zeman, a staunch supporter of ties with Beijing.

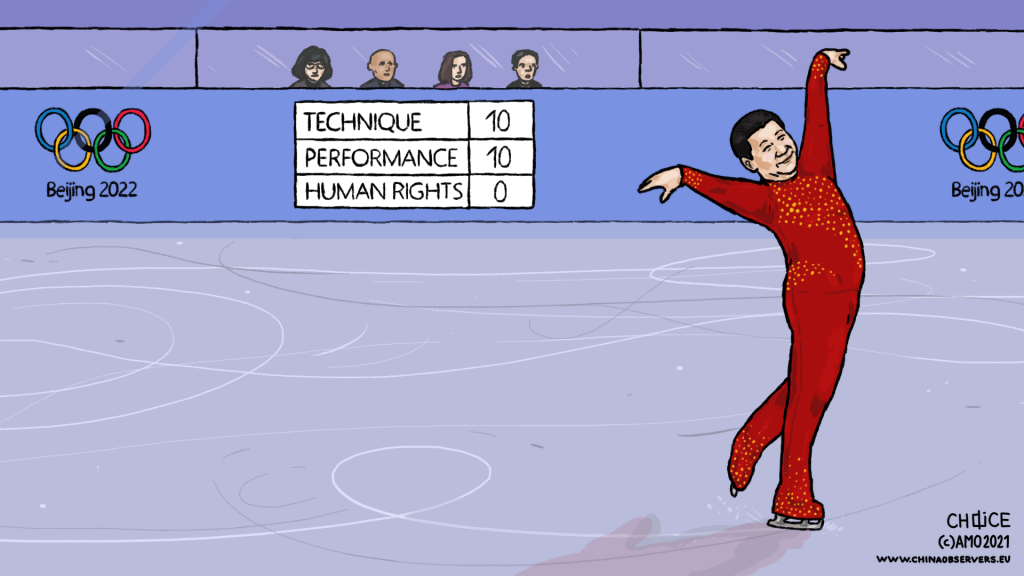

The Olympics Controversy

The recent controversy was caused by the interview of the Czech ambassador to Beijing, Vladimír Tomšík, for Chinese media in December. In the interview, Tomšík said that he had been entrusted by President Zeman to fully support the Olympics, should the President not be able to attend personally – which turned out to be the case.

In their reporting, Czech media even implied that Tomšík said that “everyone” (i.e. the Czech government included) supports the Olympics. However, this seems to be a misreading of the original statement as quoted in the Chinese media.

In any case, Ambassador Tomšík, who was previously supported for the post by the President, seems to have strayed from his mandate. As was to be expected, Czech Foreign Minister Jan Lipavský reprimanded the Ambassador, imploring him to refrain from making similar statements going forward so as to not undermine the new government’s plans of reconsidering its China policy.

In part, Tomšík’s statements were made possible by the lack of clarity on the Olympic boycott provided by the Czech government. Prior to formally taking office, Fiala’s government signaled it would decide on the issue within the cabinet, implying a formal announcement to be made prior to the games. In earlier statements, both Lipavský and Fiala indicated they would be partial to announcing a diplomatic boycott.

However, in the end, no formal decision was announced. Instead, Minister Lipavský claimed that a formal decision was not needed, as there was a tacit consensus among members of the government that was broadly understood. Separately, the Senate previously passed a largely symbolic resolution calling on the government to boycott the Olympics.

Nonetheless, the lack of an official statement appears to have offered Tomšík just enough leeway to step out of line on the matter.

Nevertheless, this was not the only incident that brought the lack of coordinated approach on the issue to the daylight. Just when the controversy seemed to be ebbing, President Zeman, in his statement to the delegation of Czech athletes to the Olympics, panned the idea of a diplomatic boycott.

“I am resolutely against misusing the Olympic idea for political aims,” Zeman declared. “Frankly said, If some political buffoons won’t [attend] the Olympics, nothing terrible will happen.”

A Dual-Track Policy?

Despite recent uncertainties about Zeman’s health, including almost a month-long stay in an intensive care unit, the president now seems likely to complete his second presidential term in 2023. His place atop Prague Castle will surely make the new government’s position on China policy harder to implement. Potentially, the division might even lead to a dual-track policy, wherein Zeman undermines the government’s efforts in a fashion now visible in the case of the Olympic boycott.

Indeed, Zeman’s desire to diminish the standing of the government, and the new foreign minister, in particular, are nothing new.

Zeman made it clear from the very beginning that he was opposed to the nomination of Lipavský from the Pirate party to the post of foreign minister. A major point of contention brought up by the President was the allegation that Lipavský lacked sufficient academic credentials to hold the post. Yet, many observers have termed the objection as a weak cover for his disagreements with the Pirate party and Lipavský’s previously stated stances on various foreign policy issues.

While Zeman eventually relented and withdrew his objections to Lipavský’s appointment, the President has made it quite clear that he will not respect Lipavský. In fact, it appears that he will diligently attempt to drive a wedge between key actors in the new coalition government.

For example, Zeman stated that he had no plans to revive the traditional meetings of the highest constitutional representatives (president, prime minister, heads of both parliament chambers) and the foreign minister on foreign policy. Instead, Zeman said he plans to discuss foreign policy issues with Prime Minister Fiala only, openly dismissing the foreign minister.

In any case, Zeman’s moves confirm his willingness to promote his own foreign policy line, while trying to ostracize his opponents from the presidential bully pulpit.

His tactic in this regard is not without precedent either. Zeman already excluded Senate president Miloš Vystrčil from the foreign policy coordination meetings due to his visit to Taiwan in autumn 2020.

In China, state media quickly jumped on the decision, portraying it as a sign that Vystrčil’s Taiwan visit went against the majority line in Prague. In the case of the Olympics, Zeman’s break with the government has once again proved popular in Chinese media.

Lipavský, on the other hand, has tried to strike a conciliatory tone with the President. The foreign minister has stressed that the President also has his role in foreign policy that needs to be taken into account. For example, Lipavský lifted his former objections to the previously planned nominees for ambassadors, some of whom are personas close to Zeman. So far, the President is not returning the charity, indicating coexistence will remain a difficult order.

Challenges Ahead

Yet, bigger challenges for the new government await. One of them is undertaking a full-scale revision of ties with China, promised in the government manifesto.

Czechia and China have officially been strategic partners since 2016, but the actual ties have remained dormant for the past few years. A major guarantee for the continuation of the status quo was President Zeman himself and the previous government of Babiš – although personally uninterested in China, the embattled prime minister was ready to give the ground on the pet issue of China policy to Zeman, lest he loses his political support. In any case, there was no appetite for making any initiative on China by the previous administration.

Now, with the new government, the opportunity to channel the actual reality of mutual relations and the gained experience into a new realistic concept of ties has finally emerged. Importantly, it remains to be seen whether some positive content can be found for bilateral relations with China and whether the new concept will go beyond managing risks, from misuse of investments for political goals to China’s propaganda efforts in the country.

Moreover, there is a question of Czech policy towards Taiwan, which also features in the government manifesto as one of the democratic partners for Czechia in the Indo-Pacific. However, Lithuania’s current predicament might discourage Czechia from following in its footsteps, for several reasons.

First of all, the internal power dynamics with the President standing against the government’s policy in Lithuania mirror the situation in Czechia. Vocally promoting ties with Taiwan might create an open “war” with the president, which China would be able to use to its advantage. Such a tactic would certainly not be alien to Beijing.

Moreover, the Chinese use of coercion against Lithuania has shown that the usual underestimation of China’s leverage by focusing solely on direct economic links that could be weaponized is no longer valid. Indeed, Czechia might be even more vulnerable to Chinese coercion via international supply chains than Lithuania, if Beijing chose to pressure German companies.

Finally, the lackluster response from the European institutions to China’s pressure on Lithuania shows that relying on a joint European position might be wishful thinking. At a minimum, Vilnius’ experience makes a case for a more measured approach on Taiwan.

In any case, troubled coexistence with President Zeman will be only one of the challenges for charting a new course of Czech policy on China. So far, the Czech policy has been rather insular in its dealings with China, not devising its approach within a larger frame of EU-China relations and its challenges. The upcoming Czech presidency of the EU in the second half of this year will be a test for whether there is actual ambition in formulating China policy also on the European level.

That is, if the current government can overcome attempts to undermine national policy by its own president in Prague Castle.

Written by

Filip Šebok

Filip Šebok is an analyst at CEIAS. He was a China Research Fellow and Project Manager at the Association for International Affairs (AMO) in Prague, Czech Republic.