It’s been only a short time since a press release by the Technical University in Košice (TUKE) appeared, claiming that the university would soon establish a joint center for artificial intelligence research in cooperation with the Chinese technology giant Huawei.

Although research cooperation with Chinese entities may be beneficial for Slovak science and research in certain circumstances, the partnership between TUKE and Huawei is an example of cooperation that brings more risks than potential benefits.

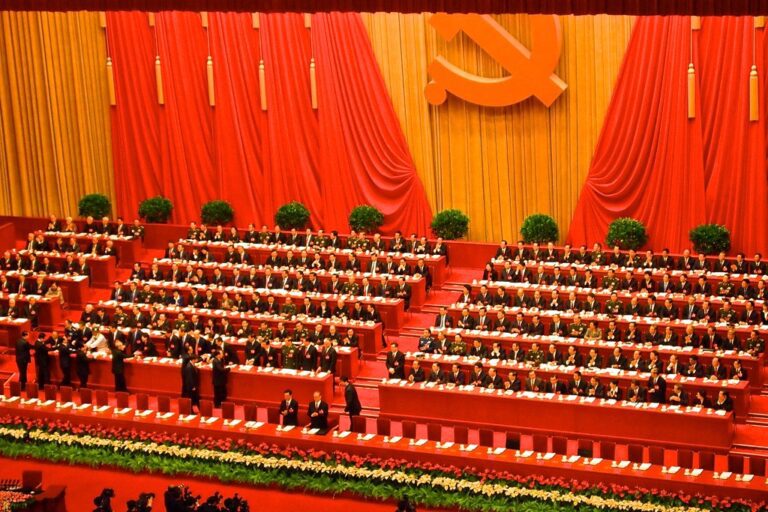

China’s Intense Interest in Technology Research

TUKE is far from the only Slovak university that maintains ties with problematic partners from China.

Research by the Central European Institute of Asian Studies found that 23 public universities and the Slovak Academy of Science (SAS), including its 26 research institutes, maintain up to 113 formal and informal links with Chinese universities and other Chinese entities. The vast majority of the cooperation is focused on the field of natural and technical sciences.

Interest in cooperation with Slovak universities has been noticeable mainly since 2012 when Slovakia became part of the 17+1 platform (then 16+1), a grouping of China and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Currently, the Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava has the most partnerships (up to 17, including hosting the Confucius Institute), followed by the aforementioned Technical University in Košice (12 links) and the top three are closed by the SAS Institute of Experimental Physics (10 relationships).

Although most of these ties do not pose a major risk, there is a group of relations that deserve more detailed attention due to the Chinese partner’s involvement in flagrant human rights violations in China, especially its Uighur population from the Xinjiang Autonomous Region, or links to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

Uyghur Racial Profiling

Huawei is one of the Chinese organizations involved in human rights abuses in Xinjiang. Recently, information came to light that in 2018 Huawei applied for registration of a patent for facial recognition technology that can apparently, among other things, recognize the ethnicity of an observed person, specifically noting an explicit ability to distinguish between Uyghurs and the Han ethnic majority. For this purpose, Huawei uses artificial intelligence (specifically machine learning technology), on the development of which it wants to cooperate with TUKE.

In addition to TUKE, the University of Žilina and the SAS Institute of Materials Science in Košice also cooperate and conduct joint research with Huawei. The supposedly “exceptional partnership” of Huawei and the University of Žilina deals with research in the field of so-called “Safe Cities”, which includes technologies aimed at recognizing faces and other objects, crowd monitoring, collecting data, or monitoring social networks.

However, Huawei is not the only Chinese company involved in mass human rights abuses in Xinjiang. In 2018, the Slovak Alexander Dubček University in Trenčín signed a memorandum of cooperation with a branch of the Chinese company Dahua. The company is mainly engaged in the development and production of surveillance equipment. Dahua has won contracts worth over $900 million from local authorities in Xinjiang to build surveillance systems. Dahua’s systems, as in the case of Huawei, are also used to recognize Uyghurs. In 2019, the US imposed sanctions on the company for this reason.

Problematic Ties to the Chinese Military

In addition to relations with Chinese companies involved in human rights abuses, relations with several Chinese universities cooperating with the Chinese military have been flagged as problematic. There are up to 25 such ties, more than half of which are with high-risk Chinese universities that possess high-level security clearances or have been involved in commercial espionage in the past.

A special place among them is occupied by relations with the so-called Seven Sons of National Defense. These are universities under the Chinese Ministry of Industry and Information Technology that focus on military technology research, with more than 30% of their graduates working for the military or defense industries.

One of the Seven Sons of National Defense – the Beijing Institute of Technology (BIT) – has relations with the aforementioned Technical University in Košice as well as the University of Žilina.

Since 2015 the Slovak Academy of Sciences has been cooperating with the Northwestern Polytechnical University (NWPU) in Xi’an. In 2019, they even agreed to set up a joint research center.

Thirdly, it is necessary to mention the Nanjing University of Natural Sciences and Technology (NJTU), which cooperates with the Technical University in Zvolen. Their joint research was even supported by a grant of almost 250 thousand euros from the Slovak Research and Development Agency.

Both the international and Slovak security communities have been drawing attention to the risks of cooperating with Chinese universities for a long time.

Last year, for example, the Slovak Information Service (Slovakia’s civilian intelligence and counterintelligence agency) publicly informed that Chinese intelligence services operating in Slovakia are trying to obtain information in the field of information and telecommunication technologies. A similar problem is described in the Security Report of the Slovak Republic for 2019, which is prepared annually by the Security Council.

Transparency Lags Behind

The mere existence of a link to a high-risk Chinese entity does not automatically mean that it will be abused. However, universities need to be vigilant in such cases and take adequate measures to minimize the likelihood of abuse of the relationship.

Currently, Slovak-Chinese academic relations suffer from a very low degree of transparency. Since 2011, the Slovak laws oblige public institutions (including universities and SAS) to publish all concluded contracts in the Central Register of Contracts. In practice, however, more than half of the agreements and memoranda concluded between universities and SAS with Chinese partners are unpublished. This also applies to cooperation with high-risk entities with a connection to the Chinese military. For example, the agreement of the SAS with Northwestern Polytechnical University on the establishment of a joint research center, or the recently signed memorandum of the Technical University in Košice with Huawei, are missing in the registry.

Even if contracts are indeed published, the quality of publication sometimes does not allow one to learn much, if anything, about cooperation. For example, the contract between Huawei and the Institute of Materials Research of the Slovak Academy of Sciences is published in such a way that its key parts are completely redacted. At the same time, the two institutions signed a Non-Disclosure Agreement regarding their cooperation.

However, ensuring transparency of these relations is not enough. It is merely a necessary first step. The most important tool that universities should implement is a systematic risk assessment before establishing relations with a Chinese entity (or any entity originating in an authoritarian country).

None of the public universities and SAS institutes carry out systematic due diligence on potential partners. The already mentioned Technical University in Košice even replied to our FOIA request that, “the risk [of cooperation] is first that we do not reach their [i.e. Chinese] level in the areas of teaching and research and there will be no interest in cooperation and support from the Chinese side.”

This quote points to the distressingly persistent perception that China is too far away to pose a relevant security risk and is more of an opportunity for Slovakia to develop. However, the recently adopted Security Strategy of the Slovak Republic indicates that the security apparatus is beginning to register these risks.

The risk assessment itself must also end in the form of taking concrete measures to prevent possible abuse. An example could be the exclusion of dual-use technology research from joint activities. However, if the risk examination reveals that a potential partner is involved in human rights violations, cooperation should not be established at all, as this is behavior in absolute opposition to the constitutional values of the Slovak Republic, which should be upheld by academia.

In truth, the appeal for a responsible approach to academic cooperation with China should come mainly from the academic community itself. The Ministry of Education and other state bodies can provide consultations and help set up a standardized risk assessment system, but unless there is adequate interest among university administrators in tackling this problem, any “top-down” regulation will be just another bureaucratic burden rather than a real solution.

Written by

Matej Šimalčík

MatejSimalcikMatej Šimalčík is Executive Director of the Central European Institute of Asian Studies, a think tank based in Slovakia, and a European China Policy Fellow at MERICS. He is a member of MapInfluenCE, a regional initiative aimed at monitoring China’s economic and political influence in Central Europe, where he acts as an analyst for Slovakia.