Speaking in July 2018, then European Commissioner for Enlargement Johannes Hanh referred to Balkan countries that were the recipients of Chinese infrastructure financing, like Serbia and Montenegro, as China’s potential Trojan horses among future EU members. The logic of the Trojan horse appears salient for Serbia these days, as Belgrade is breaking its tradition of staying neutral on significant international issues and is now backing China diplomatically. However, this is opportunistic behavior that will not last indefinitely.

The Story Behind the Relationship

Ever since the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) reached the Balkans, the idea of the Trojan horse has been circulating. This notion implies that the countries covered by the BRI project would either accumulate unbearable Chinese debt, through so-called “debt trap diplomacy”, or they would be more susceptible to Chinese political influence. That way, these countries would not only be friendly towards China, but they would also increase the number of Chinese allies in the EU and dilute the EU’s ability to implement a more assertive China policy.

While there is undoubtedly some truth to this hypothesis, this is not a prevalent Chinese calculation regarding Serbia, as China already has friendly countries from Southeast Europe within the EU. Over the years, Greece has vetoed the EU’s efforts to condemn China on human rights and the law of the sea. Chinese financing for a Budapest-Belgrade railway has built influence in Hungary as well. For China, Serbia and the Balkans are of interest primarily due to the strategic geography that puts Belgrade and its neighbors at the crossroads between Europe and wider Eurasia. Nevertheless, Serbia is still a nice, small point for Beijing to score in expanding the list of countries that do not condemn China internationally.

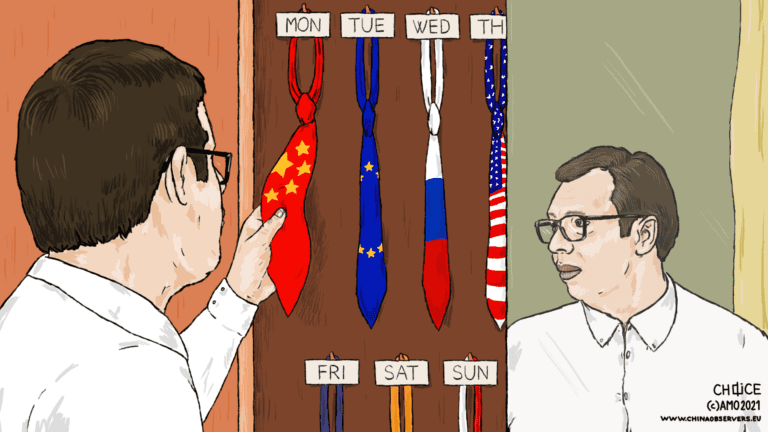

The Serbian story began in 2008 with Kosovo’s independence, when Serbian foreign policymakers started to create a separation between countries recognizing an independent Kosovo and those that did not. Encouraged by both Chinese non-recognition of Kosovo and in search of commercial opportunities after the global financial crisis, Serbia signed a strategic partnership agreement with China, while calling China “the fourth pillar of Serbian foreign policy” alongside the EU, Russia and the US.

In 2010 out of solidarity with China, Serbia boycotted the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in Oslo honoring Chinese human rights advocate Liu Xiaobo. Yet, after being the only EU candidate that wanted to abstain from the ceremony, Serbia changed its position due to EU pressure and sent Ombudsman Saša Janković to attend. In other cases, Serbia avoided articulating a clear stance on major international issues fearing that it would endanger its Kosovo policy. The most famous example of flying below the radar and avoiding taking a clear stance is the Serbian decision not to introduce sanctions against Russia for the annexation of Crimea and consequently, not to join the EU in its Russia policy.

Up until now, the only countries for which Serbia has changed its foreign policy tendency of flying ‘under the radar’ have been Israel and China. In March 2020, Serbia decided to open “an official state office” in Jerusalem, after years of Serbian diplomacy laying low on the Israel and Palestine issue. This move still did not represent a 180-degree turn for Serbia as it has not joined the few countries to open embassies in Jerusalem.

Where Others Failed, China Succeeded

However, with China, things are different. In December 2019, Marko Đurić, the director of the Office for Kosovo and Metohija and the vice president of the ruling Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), provided an interview to Xinhua, the Chinese state press agency. Đurić expressed support for the Chinese policy on Xinjiang as he described the policies targetting minority groups as a fight against terrorism and extremism in the region. Đurić also lauded the protection of minority rights in Xinjiang while accusing the West and its media of hypocrisy.

Now there is an even more brazen change in Serbian policy. In an open letter to his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, the Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić expressed support for the controversial national security law for Hong Kong that endangers the “one country, two systems” principle. In the letter, Vučić wrote that “As an independent country, Serbia is against any interference with internal affairs of a sovereign country.” The letter also stated that “Serbia and China are committed to respecting international law globally” and that Serbia “condemns any attempts at undermining the reunification” of China.

More recently, Serbia was also the only European country alongside Russia that signed a joint statement issued by the Permanent Mission of Belarus at the 44th session of the UN Human Rights Council. The signatories “urge refraining from making unfounded allegations against China based on disinformation”, while complimenting China’s work to improve living standards and human rights in the region while combating terrorism and extremism.

Nothing Lasts Forever

Why is Serbia so eager to support China? There are three reasons. First, Serbia is replacing Russia with China as its primary partner in the East. The only thing maintaining the special relationship between Moscow and Belgrade is the Kosovo dispute, even though the two sides do not trust each other and have different strategic interests. As both the EU and the US are impatient to resolve the Kosovo dispute, Serbia will keep China close by, although it is hard to expect that China will suddenly become active in the dispute. Second, Serbia’s EU path is a difficult process with an uncertain future. The roadblocks on the journey will make China an important partner, particularly when it comes to investment and infrastructural loans. Ultimately, the ruling SNS is using China to promote itself domestically and taking credit for developing the partnership with China and bringing in Chinese capital into the country. We have seen this from the way Serbian leadership enthusiastically embraced China’s “mask diplomacy” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This new trend in Serbian foreign policy is not permanent realignment, but a case of opportunism pursued as long as Serbia has leeway for it, and as long Serbia is not paying a high price for its partnership with China. Serbia cannot give up on EU accession as the country is dependent on the EU. However, given that EU membership is a long-term prospect, in the short and medium term, Serbia will try to extract as much benefit as it can from doing business with China and other geopolitical players. In the past, Serbian leadership would give up on some of its initiatives as soon as it became too risky for Belgrade, as in the case of the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize ceremony. In 2018, under EU pressure, Serbia canceled its visa-free regime with Iran as Iranians were abusing the visa-free regime to relocate to Europe. In another case, in December 2019, Serbia decided to stop buying weaponry from Russia in order to avoid US financial sanctions. Therefore, Serbia will continue on its current trajectory as long as there is no risk attached. The moment it becomes too hot, Serbia will step back. As it usually does.

Written by

Vuk Vuksanovic

v_vuksanovicVuk Vuksanovic is a PhD Researcher in international relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), an Associate of LSE IDEAS, LSE’s foreign policy think tank, and a Researcher at the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy (BCSP).