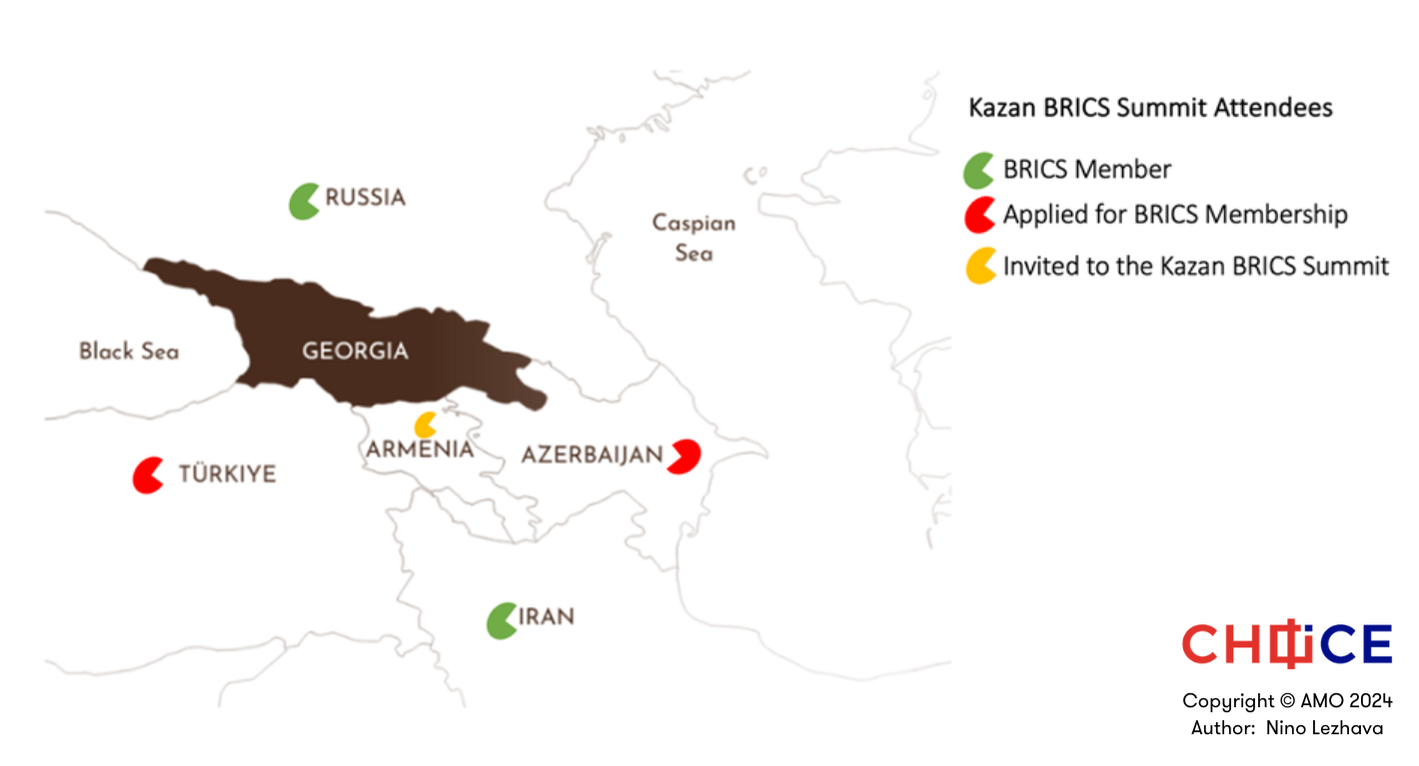

At the 16th BRICS summit that took place in Kazan from October 22 to October 24, 2024, leaders from the Black Sea and the South Caucasus regions highlighted their broader geopolitical and geo-economic ambitions through alignment with China’s global development agenda. With Türkiye and Azerbaijan having formally applied for BRICS membership, and Armenia receiving an invitation from Russia, Georgia was the only regional country absent from this growing geopolitical bloc.

Although the enlargement bid ultimately fell through, the trio’s presence at the summit signaled a significant shift in the region’s geopolitical landscape, raising critical questions: What does this mean for the South Caucasus and the Black Sea, especially as China’s influence within BRICS continues to grow? Will this advance Beijing’s grand strategic objectives in these two regions? And if so, how?

Map I – Caucasus and its Wider Neighborhood

Türkiye’s Next Move

Among both BRICS members and candidates, Türkiye stands out due to its status as a NATO ally and an EU candidate country. Ankara’s bid to join BRICS reflects its desire to diversify its economic partnerships and reduce dependence on the West. Indeed, Türkiye’s application to join the bloc, which came as no surprise, aligns with the country’s long-standing frustration with its stalled EU membership process and pressing financial needs, with Ankara seeking greater strategic autonomy and market diversification in the face of these challenges.

Erdoğan’s foreign policy has always been a balancing act, positioning Türkiye between competing spheres of influence, although the BRICS membership would have implications beyond this delicate balance. Türkiye’s position as the second-largest military force in NATO, coupled with its near-exclusive control over the Black Sea under the Montreux Convention, provides it with significant leverage.

And while Türkiye’s application was rejected at the Kazan summit, this setback does not preclude Ankara from re-applying in the future. Beijing recognizes the strategic potential of cooperating with Türkiye, which could further enhance China’s influence (including its economic leverage) not only in the Caucasus and Black Sea but also in the Balkans, Middle East, and Central Asia, while undermining US and NATO influence. However, Beijing is in no rush to include Ankara, as the two already share a vision “for a fairer global order,” which puts the unity and the reputation of NATO under question.

From an economic perspective, Türkiye is an important member of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), accounting for approximately 1.3 percent of total BRI investments, with its involvement in the Middle Corridor being particularly attractive to China. At the same time, while China is Türkiye’s second-largest trading partner, and the two countries cooperate across several sectors like nuclear and renewable energy, mining and manufacturing (including of electric vehicles), Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in Türkiye still lags behind European investments.

Integrating Türkiye into BRICS could strengthen China’s control over this critical crossroads, further expanding its access to global markets. Nevertheless, Beijing remains cautious, aware that the timing must be right for a more substantial and deeper engagement. As for Türkiye, a BRICS membership would give it a voice in shaping global economic policies, particularly as the bloc encompasses 29 percent of global GDP, 43 percent of oil production, and 25 percent of global exports. This could, however, come at the cost of Ankara’s estrangement from the West, putting the Black Sea and South Caucasus regions under greater Chinese influence while raising concerns about Chinese economic statecraft, non-value-based partnerships, and democratic backsliding.

Unlikely Attendees

A year ago, it would have seemed improbable that the leaders from Amenia and Azerbaijan – historic adversaries from the South Caucasus – would attend a BRICS summit to discuss peace and cooperation. Yet, in Kazan, both countries participated in a discussion focused on regional stability, deemed essential for expanding their respective roles in international trade, supply chains, and transportation networks. China has successfully capitalized on this rare moment of convergence. It offered both Armenia and Azerbaijan increased investments while aligning BRICS infrastructure projects with the BRI, thus serving Beijing’s broader goal of exerting greater control over vital economic pathways.

The presence of Azerbaijani and Armenian leaders in Kazan also highlighted the growing proximity of BRICS to the South Caucasus, with China positioning itself as a key player in the region, alongside Russia and Iran. This further legitimizes the BRICS format and casts a shadow over years of Western-led efforts to resolve the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

At the same time, Armenia’s and Azerbaijan’s readiness to partner with BRICS is based on their immediate needs to diversify their export markets and improve infrastructure. Armenia is unable to pursue its foreign policy in isolation and requires pragmatic decision-making. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan – already a strategic partner of China – seeks to expand its global economic footprint, with the country’s energy resources, strategic position at the Caspian Sea, and a vital role in the Middle Corridor, making it an attractive partner for Beijing. Ahead of the COP29 summit, Baku has further emphasized cooperation in green energy, with Chinese companies already involved in the region’s renewable energy projects, including plans to power Nagorno-Karabakh with solar energy.

Future Prospects

In 2014, BRICS members Brazil, China, India, and South Africa abstained from voting on a UN General Assembly resolution supporting Ukraine’s territorial integrity following Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Today, China continues to downplay its role in the war in Ukraine, supporting Russia.

While endorsing the UN values in theoretical terms, BRICS operates as a non-ideological platform that challenges the existing international order, including the Westphalian principle of state sovereignty. Russia’s expansionist policies exemplify this stance. Neither Moscow nor Beijing, nor their allies, are likely to champion – let alone defend – the sovereignty and territorial integrity of weaker states, particularly if those states lack Western support. Considering the complex interdependencies, even the US and the EU struggle to reduce their reliance on China. In this context, smaller countries may find themselves entering asymmetric dependencies through Chinese industrial and infrastructural expansion.

Given Azerbaijan’s increasingly important role in European energy supplies, the EU is closely monitoring the Sino-Azerbaijani partnership. The same applies to the BRICS. Brussels has invested billions in the Middle Corridor to reduce its own reliance on Russia while minimizing the risks of expanding Chinese and BRICS influence. And while the EU continues to engage with individual BRICS Plus countries, sharp divergences between the two blocs – as seen in their respective stances and responses to the ongoing conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza –complicate these relations. Armenia also faces a delicate balancing act as it pivots between its desire for pragmatic multilateralism and aspirations toward the EU.

Moreover, as China’s infrastructural footprint grows in the South Caucasus, Georgia –strategically positioned with an access to the Black Sea – may soon become an additional target for BRICS cooperation. With its democratic backsliding and decline of its Euro-Atlantic aspirations, Tbilisi may eventually be drawn into the BRICS bloc. If that happens, the South Caucasus region could find itself fully surrounded by BRICS, which would most likely reshape the geopolitical landscape and potentially strengthen authoritarian regimes in the region. The West must, therefore, act swiftly and develop a tailored strategy for these two regions to prevent further erosion of its influence in this rapidly evolving industrial and ideological contest.

Written by

Nino Lezhava

NinoLezhava13Nino Lezhava is a research analyst based in Georgia, specializing in the South Caucasus and the Black Sea regions, with a particular focus on geopolitical competition, Euro-Atlantic relations, and hybrid warfare. She lectures at universities in Germany and Georgia; writes as a freelance contributor for various media outlets, including CEPA and New Eastern Europe; and contributes her expertise as a parliamentary researcher in Georgia. She has also worked at the Georgian Defense Forces, NATO and OSCE.