Xi Jinping’s call for the “normalization” of politics in Xinjiang does not signal the end of the repressive policies in the northwestern province. Instead, it marks a shift from the “strike hard” campaign to the next phase of assimilating Uyghur culture into a CCP-approved version of a unified Chinese identity, intended for external propaganda. The narrative is simple, but effective: by emphasizing development achievements and showcasing the improved living conditions of Uyghurs and other minorities under CCP leadership, China aims to promote its own model of human rights to the world.

This August marks the one-year anniversary of Xi Jinping’s most recent visit to Xinjiang. During this second trip since his rise to power, Xi praised the “hard-won social stability” and called for the “normalization” of politics, emphasizing the need to tell a better story of Xinjiang to both domestic and international audiences. This seems to signify a major shift from the previous “strike hard” campaign, which imposed hard punishments and repressive measures on Uyghurs and other minorities in the Muslim-majority region. The long-term plan for Xinjiang continues to focus on three core objectives: maintaining social stability, advancing development, and forging a unified Chinese identity.

China’s Narrative for Xinjiang

Xinjiang is at the center of human rights debates between China and the West. Activists and Western governments have long criticized the CCP’s repressive policies as violations of human rights, which the Chinese government has consistently denied. Instead, state media and officials highlight Xinjiang’s economic development as evidence of the success of past policies, promoting a Chinese concept of human rights that prioritizes the right to development and survival as fundamental. The CCP views development as a pre-condition for the realization of human rights and has become increasingly pro-active in sharing and promoting China’s approach to the international human rights system, with Xinjiang serving as a key example.

The economic development in Xinjiang is undeniable. In July, during the 8th China-Eurasia Expo in Urumqi, trade contracts worth $16 billion were signed as part of the promotion of the newly introduced China (Xinjiang) Pilot Free Trade Zone (FTZ). Xinjiang is home to the world’s largest solar farm, produces 20% of the world’s cotton, and has recently became a key research hub for China’s food security, with significant funding directed toward rice and wheat farming projects. Xi Jinping described Xinjiang as the “gateway for China’s westward opening up.”

While these economic successes are tied to improvements in the general living conditions in the region, it remains questionable how much Uyghurs and other minorities genuinely benefit from these projects and what the true cost of this development is.

The CCP’s focus is on showcasing the achievements of China’s approach to human rights through the promotion of development, with Uyghurs increasingly highlighted not only in the context of poverty alleviation, but also as representatives of a minority group benefiting from Chinese development policies and as symbols of a unified Chinese identity.

Tourism merges economic development with the narrative of “social stability,” playing a central role in promoting a more favorable story of Xinjiang. In recent years, the Chinese government has sought to paint a positive image of Xinjiang by showcasing Uyghur heritage and culture as a major attraction for tourists. Uyghurs are often depicted dancing, celebrating Muslim festivals, and wearing their traditional clothes. This portrayal serves to present the region’s diverse culture and development achievements to both domestic and international audiences, aiming to convince them that all is well in Xinjiang.

Assimilation of Uyghur culture

While the display of cultural heritage is prominently featured in the portrayal of Xinjiang’s development, Uyghur culture is clearly subordinate to Chinese culture. As Pan Yue, director of the National Ethnic Affairs Commission, states, Chinese culture serves as the binding element to create a unified Chinese identity, with ethnic minorities seen as “contributors to Chinese culture.” When officials describe Chinese identity as an inclusive umbrella term, it actually refers to a tightly controlled portrayal of ethnic minority cultures, limited to showcasing the success of a unified Chinese nation. This is not only achieved through external propaganda but (unsurprisingly) also through repressive policies aimed at assimilating and Sinicizing ethnic minorities.

In the case of Xinjiang, multiple reports and articles depict efforts to sanitize Uyghur culture to align with the CCP narrative. While Chinese state media showed images of Uyghurs celebrating Eid al-Fitr (the end of Ramadan), the reality has been that Muslims could not freely practice their religion. Officials organized festivals, such as art events, during the day and provided free food to encourage dancing and entertainment, rather than prayer and fasting. Schools and training institutions were prohibited from offering religious services to students. They were also required to distribute surveys asking students about their family’s habits, including whether they fast. Lectures on maintaining social order and stability, as well as health-related topics emphasizing regular meals, were scheduled during the hours of breaking the fast. These measures and restrictions were not only directed at Uyghurs, but also targeted Muslims in other provinces, such as Gansu. Furthermore, no Uyghur from Xinjiang participated in the hajj pilgrimage, which, like fasting during Ramadan, is one of the Five Pillars of Islam.

These measures extend beyond religion, affecting other cultural aspects that hinder complete assimilation, such as the Uyghur language. Children are separated from their families and forced to attend boarding schools, where classes are taught exclusively in Mandarin. The names of hundreds of villages have been changed, removing references to Uyghur culture, religion, and history, replacing them with terms aligned with CCP ideology and unified Chinese identity, such as “happiness” and “harmony.” In one case, a village was renamed “Unity Village”.

The result of these policies is not only the maintenance of “social stability,” but also the creation of another CCP-approved narrative of “happy dancing minorities” that serves as an image booster and proof of the supposed successes of the Chinese model.

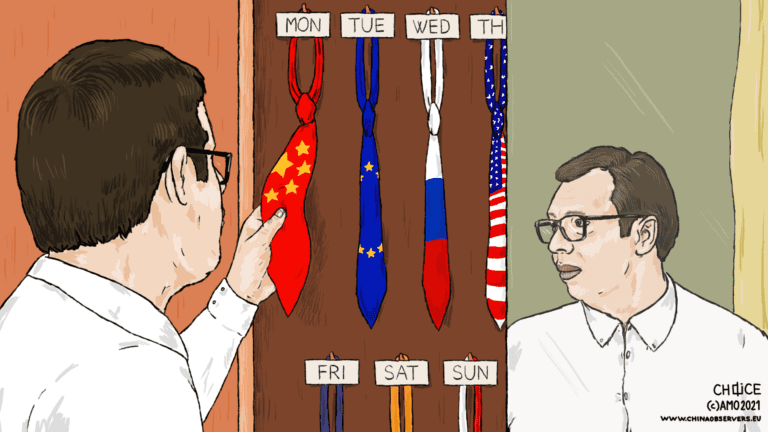

Promoting the Chinese Model

Beijing invites journalists, politicians and researchers from various countries to “see Xinjiang with their own eyes” on carefully orchestrated tours designed to internalize and spread images and stories of improved living conditions and the preservation of Uyghur heritage to an international audience. As the Chinese government faces reputation damage from allegations of human rights violations in Xinjiang, the portrayal of a flourishing economy alongside a pro-active construction of a unified Chinese identity acts as a strategy to win the “hearts and minds,” particularly in Arab countries and the Global South. This narrative aims to project a message of a rapidly developing, diverse yet united Xinjiang under CCP leadership, contradicting Western accusations and presenting an alternative model to Western concepts of human rights and development.

Political decision-makers in Europe and beyond should be mindful of the intertwined reality of economic development and forced assimilation when addressing the situation in Xinjiang. What the Chinese state media share in hundreds of articles as a success story of human rights in Xinjiang is, in fact, a CCP-approved narrative. This narrative selectively preserves certain cultural aspects to showcase the success of China’s concepts and values, particularly emphasizing the prioritized role of the right to survival and development as central to human rights. Recipients of this narrative should recognize that the concepts of “normalization” and “maintaining social stability” for development primarily serve the interests of the CCP, not those of the Uyghurs and other minorities. Ultimately, they only benefit from Xinjiang’s development as long as they conform to the image that the CCP crafted for them.

Written by

Janina Mansel

Janina Mansel recently completed a master’s degree in Chinese studies from Freie Universität Berlin. She also holds a bachelor’s degree in Sinology from the University of Leipzig and spent three semesters studying abroad at Peking University and Henan University in China. Her research interests focus on China's foreign policy, soft power construction, and party-state ideology.