The following article represents a first pilot attempt by the Women Insight on China (WiCH) initiative to audit gender representation in Europe’s China discourse.

Public debates about China policy matter – not only because they shape Europe’s collective understanding of Beijing’s actions, but also because they decide whose experience and voice defines that understanding. Yet, looking closely at who actually speaks about China in Europe’s think tanks, conferences, and podcasts, a clear gender imbalance appears.

The Sound of Silence: Who Speaks to Europe on China?

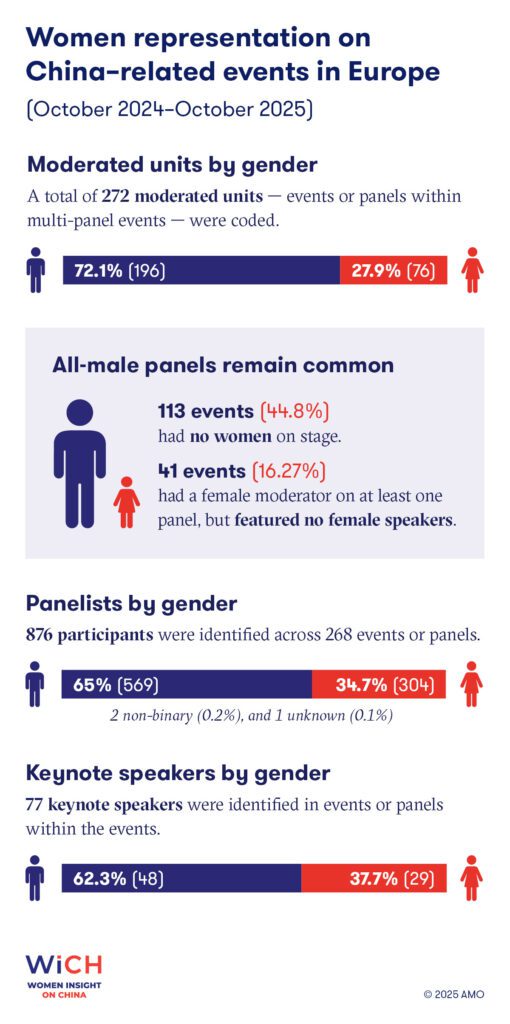

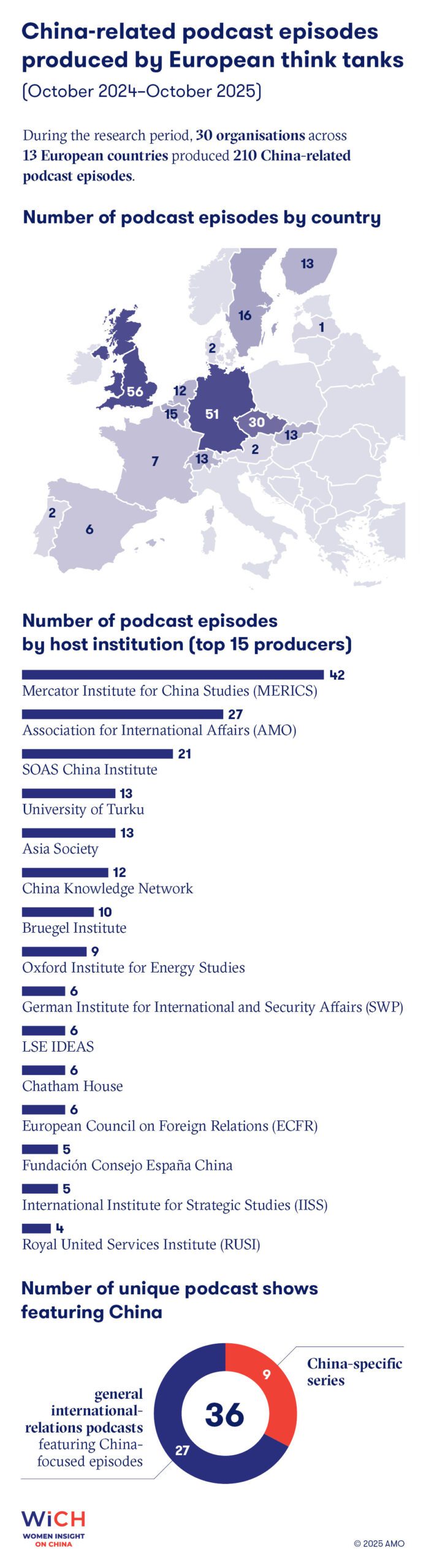

Between October 2024 and October 2025, Women Insight on China (WiCH) initiative tracked gender representation across 268 events and 210 podcast episodes organized by 63 European think tanks. The results are as revealing as they are sobering: men made up roughly two-thirds of all speakers, while women accounted for just 34.7 percent. Two participants identified as non-binary, and one preferred not to disclose gender identity.

Despite growing awareness of ‘manels’ (all-male panels), they remain stubbornly present: 44.8 percent of all China-related events in Europe featured only men. Another 16 percent included a woman moderator but no female speakers. In total, nearly two-thirds of all moderated sessions had no woman in a speaking role at the stage.

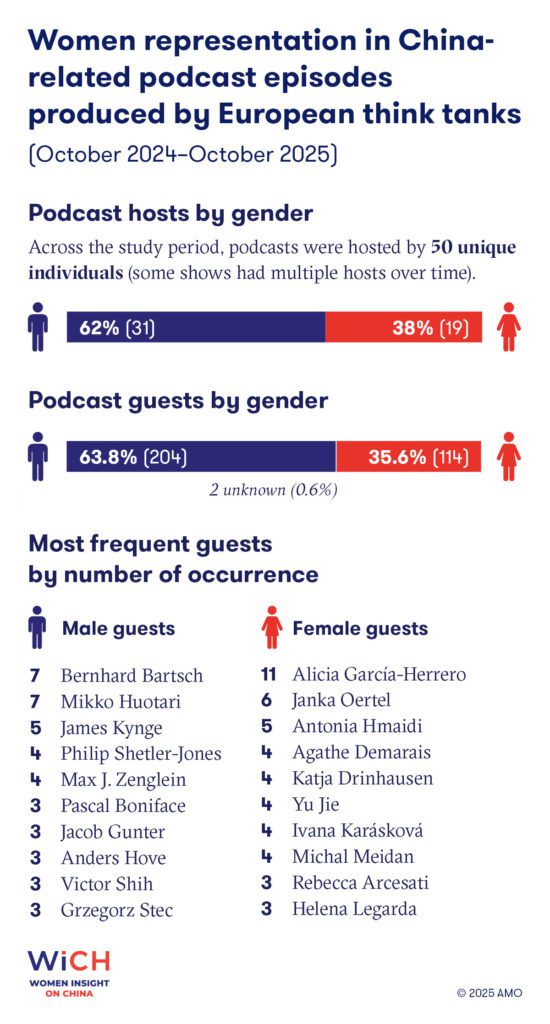

Podcast episodes produced by renowned think tanks and universities leading the China research in Europe were not better: 63.8 percent of guests and 62 percent of hosts were men.

So, to borrow (and lightly reimagine) Bob Dylan’s famous refrain: where have all the China girls gone?

The Missing Middle: From Lecture Halls to Empty Chairs

Anyone familiar with European universities knows that China studies is not a particularly male-dominated subject. Lecture halls in London, Berlin, Prague, or Warsaw are full of young women dissecting China’s political system, studying Mandarin, and producing essays on Chinese foreign policy, economy, security or society. Yet somewhere between the lecture hall and the public stage, many of these women quietly disappear from view.

Some pursue other careers – in diplomacy, the private sector, or international organizations. Others relocate or start families. And some simply decide not to enter the fast, competitive, grant-driven, and high-visibility environment of European think tanks. But there is likely something deeper at play. Once in the policy ecosystem, visibility is often determined less by what you know and more by who you know. Informal networks, reputation within specific research communities, and personal confidence all shape who gets invited to speak. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle: if few women are visible as keynote speakers, panelists, podcast hosts or moderators, they are less likely to be invited again.

This imbalance isn’t about ability. It’s about structure. The think tank world rewards agility, networking, and the capacity to operate in fast-paced media cycles. Those who hesitate or lack access to established circles risk being overlooked, regardless of expertise. In such an environment, confidence sometimes counts as much as competence. Women – especially those early in their careers – may be less inclined to self-promote or to assert authority in a public forum, leading organizers to default to the familiar and already-visible names, who are often male.

The data suggest that differences in gender representation are not primarily geographical but rather reflect distinct institutional cultures and event-planning habits. Across Europe, well- and poorly-performing organisations can often be found within the same country – and sometimes even within the same city. Some institutions have managed to ensure at least partial gender balance, while others continue to feature programs or podcast line-ups dominated almost entirely by men. These discrepancies point less to national context than to how individual organisations approach visibility, expertise, and inclusion when deciding who gets to speak about China.

Moderation is the role showing the most disparity (even though women were in 41 instances moderating manels) with only 27.9 percent of women moderators. This result is even more striking when examining the individuals featured most frequently as moderators: the top five male moderators collectively moderated 29 sessions, compared to just 14 sessions for the top five female moderators. In other words, male China experts are twice as likely to be invited to lead discussions than their female peers.

While podcasts might seem a more flexible and accessible format than events, the WiCH data reveal another structural quirk. The most frequent female voice in Europe’s China-related podcasts, Alicia García-Herrero, owes her prominence largely to co-hosting Bruegel’s own China-focused show. Out of her eleven podcast appearances during the research period, ten were on her own platform. A similar pattern emerges elsewhere: MERICS experts such as Rebecca Arcesati, Katja Drinhausen, Antonia Hmaidi and Helena Legarda appeared almost exclusively (within the constraints of the chosen methodology, i.e., focusing on Europe only) on their institution’s in-house podcasts, while Ivana Karásková, founder of CHOICE, featured primarily on her own initiative’s channels. In other words, female analysts are most frequently heard when they – or their institutions – control the microphone. So if you want to be heard as a female China analyst, the best way may simply be to join an institution that produces China-focused podcasts – or start your own.

It generally seems that institutions which invite less women on their events stage keep them even further away from the podcast microphones. One institution notably featured 20 percent of female speakers in their events; its podcast series on China merely included three women out of its 21 guests (incidentally two of these women spoke about a female writer, and the third talked about gender in China). WiCH analysis of think tanks’ podcasts and their guests further confirm that representation of women’s voices seems to be related to institutions’ inner culture.

WiCH’s team quietly noted which organizations consistently performed worst in terms of representation. The initiative plans to reach out to some of these institutions in the coming months to offer data-driven feedback and support on how to improve inclusivity in future programming. The aim is constructive: to help think tanks reflect on how speakers are chosen and how talent pipelines might be broadened. Some organizations have already responded positively, asking for recommendations.

Closing the Loop: Make the Stage More Welcoming

Public-facing panels and podcasts are not just communications tools; they are gateways to influence. Speaking at an event or being quoted on a podcast translates into recognition, citations, and media visibility. These are the currencies that shape whose expertise ultimately matters.

If women are underrepresented in these public platforms, the result is a narrower discourse – one that inadvertently sidelines half of the intellectual potential available to Europe’s China-watching community. And that, in turn, limits the diversity of insights that inform European policy thinking toward China.

Importantly, the data do not imply that institutions are deliberately excluding women. Rather, they point to patterns, deeply embedded in professional culture, of who is remembered, recommended, and re-invited. Organizers under time pressure often default to the “usuals.” Editors and moderators look for guests who are quick to respond or known to them. In such a system, visibility becomes self-perpetuating. The absence of women on panels is not always intentional, but it is still consequential.

The gender gap in China policy debates is not rooted in a lack of female expertise, but rather in the lack of recognition. WiCH audit shows that dozens of highly qualified women across Europe are producing excellent work on Chinese politics, economy, security, society and technology. Ensuring they are part of the public expert conversation simply requires intentionality and perhaps a small adjustment in how think tanks curate their stages.

WiCH would like to follow with several practical suggestions which could help. Compiling databases of experts, committing to “no manels” policies, or including early-career analysts as discussants are small interventions that can have outsized effects. Some institutions have already shown that deliberate inclusivity does not compromise quality. It enriches the debate by bringing in perspectives that would otherwise remain unheard.

Beyond the numbers, one question remains: how can Europe make sure that the women who once filled its China studies classrooms find reasons and opportunities to stay in the field?

Next year, when this mapping is repeated, we may find that the picture looks a little different – perhaps a little fairer and a little more balanced – thanks to the awareness this first audit will have sparked among institutions and organizers. Otherwise, we will be left wondering as Dylan might have put it: when will they ever learn?

The WiCH infographics are available below for download. Institutions that recognize themselves in the data are encouraged to reflect, engage, and, where possible, lead by example.

WHERE ARE

EUROPE’S WOMEN

CHINA EXPERTS?

November 2025

by WiCH

Written by

Ivana Karásková

ivana_karaskovaIvana Karásková, Ph.D., is a Founder and Lead of CHOICE & China Projects Lead at the Association for International Affairs (AMO) in Prague, Czech Republic. She is a an ex-Fulbright scholar at Columbia University, NYC, a member of Hybrid CoE in Helsinki and European China Policy Fellow at MERICS in Berlin. She advised the Vice-President of the European Commission, Věra Jourová, on Defense of Democracy Package.

Emma Belmonte

Emma Belmonte is China Projects Analyst at AMO, specializing in Beijing’s influence on European political discourse, Chinese security and law enforcement activities in Europe, and Taiwan-Europe cooperation. Emma has been working as a reporter specialized on Chinese speaking regions, has conducted on the ground reporting in both Taiwan and China and written multiple feature articles for publications including GEO magazine, Figaro Magazine, Asialyst, the Green European Journal. She holds a Master’s degree in Modern Chinese Studies from the University of Oxford and a Bachelor’s degree in Philosophy from the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Lyon.