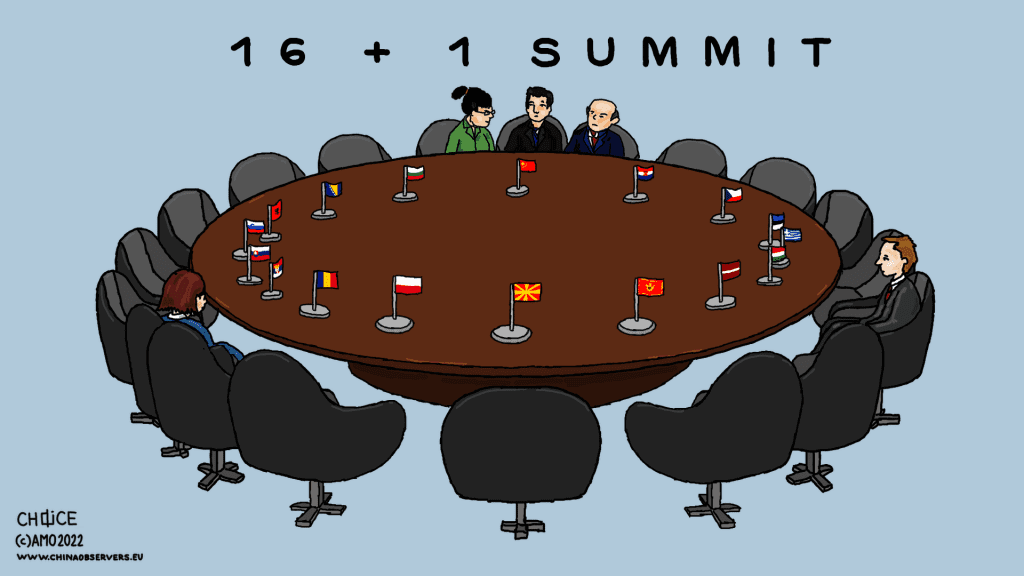

When Will the Czech Republic Exit the 16+1?

After the new Czech government was formed last December, one of the pending questions was when the country would leave the China-led format for cooperation with Central and Eastern European countries, known as the “16+1.” Indeed, over the past months, a more China-skeptic approach was manifested in bolstering cooperation with Taiwan and reinvigorating the focus on human rights in Czech foreign policy. Still, the government has not yet announced the long-expected exit. Why?

The domestic political backdrop plays a key role in understanding the current Czech government’s policy on China. A decade ago, when China started courting Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), the Chinese interest was initially met with enthusiasm from the Czech political elites. Petr Nečas’s government (2010-2013) perceived China as an economic alternative to the western markets, still recovering from the effects of the global financial crisis. As the Czech Republic lacked previous direct experience with and elaborate current knowledge of China, it tended to consider the country to be yet another Asian investor, on par with Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, all of them long present in the Czech economic space by then.

Pipe Dream of Chinese Investment

Misunderstanding the political motivation behind China’s economic policy towards the region, the Czech government emphasized only attracting Chinese FDI to the country and perceived economic opportunities for Czech companies in the Chinese market. The following Social Democratic government (2014-2017), backed on this issue by President Miloš Zeman, went even further and initiated a so-called “restart” of the Czech policy towards China. Leading politicians claimed that the previous governments’ focus on human rights (a mainstay of the Czech China policy since 1989) damaged Czechia’s economic prospects. Instead, a new “pragmatic policy” was proposed, prioritizing economic benefits over human rights concerns.

Not much changed in this regard when the government was replaced in 2017. New Prime Minister Andrej Babiš was indifferent to China and let the Social Democrats, a coalition partner ruling the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and President Miloš Zeman effectively run China affairs.

When it comes to the 16+1, past Czech governments perceived it as a tool for keeping China interested in the region. The participation in the format should have ensured access to the top echelons of the Chinese power and enabled Prague to play a prominent role as “China’s gateway to Europe.”

However, there was a price to pay. Outside the region, the remaining EU members and the European Commission considered the format a Chinese Trojan horse. They accused it of undermining the EU’s (sometimes rather imagined and ephemeral) unity on China. On the Czech domestic front, the opposition found the non-transparent dealings with an authoritarian regime in China not only morally problematic but also pointed out the fact that the alleged benefits of intensified bilateral ties had not translated into promised economic benefits.

Moreover, the Czech Republic’s counterintelligence service has repeatedly warned of China’s growing influence on domestic politics, policies, and politicians. Civil society organizations and investigative journalists have documented cases of China’s manipulation of media discourse, penetration of the academia and think tanks, and attempts to spread China-positive narratives through Czech mainstream and alternative media and social media.

It became clear that an actor with allegedly strictly economic interests was apparently active in other areas as well.

Should I stay or Should I Go Now?

While in opposition, the members of the center-right coalition SPOLU and the centrist coalition of the Pirates and the Mayors and Independents (STAN) were quite critical of China and vouched to change the course of Czech China policy when in power. However, criticizing a policy while in opposition and changing a policy course when in power are two different things. Any substantive move which may be interpreted as unfriendly towards China can go directly against the wishes of President Miloš Zeman, who allegedly – at one point of time – considered the “restart” of Czech China policy his biggest foreign policy achievement.

If the president feels aggrieved by the government’s ‘dismantling’ of his political legacy, he may well become uncooperative in domestic legislative processes. This may not be convenient for the ruling political parties, especially when preoccupied with preparations for the Senate and municipal elections to be held in September and presidential elections in January 2023.

Moreover, Zeman has already shown on other occasions that he is willing to divert from the country’s policy on China as defined by the government and charge his own course, including issuing instructions to the Czech Ambassador to Beijing contradicting the government’s wishes, communicating directly with the Chinese president or not following the talking points prepared for him by the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The government would thus not only risk a direct confrontation with the president on the issue of limited practical importance but it could be also embarrassed at the end of the process. For example, in a hypothetical scenario, President Zeman could attend a gathering of the 16+1 format even after the Czech government announced it no longer participates in it.

Ironically, the exit from the 16+1 may not be welcome by the EU either. The Czech Republic currently presides over the European Council in the rotating presidency which it will hold until December. The situation is already complicated by the war in Ukraine, looming energy crisis, and rising inflation in Europe. A ‘radical,’ unilateral action of an EU member state towards China – that some in the European Commission and European capitals may fear, having in mind the case of Lithuania’s spat with Beijing – would add a rift with a major economic power to the list of EU immediate problems. At the least, such a development would further deteriorate already sour EU-China relations.

New Roadmap: Exit in 2023

As a result of domestic politics and international concerns, the Czech government’s moves towards China have been cautious, largely confined to the personal initiative of Jan Lipavský, Minister of Foreign Affairs (Pirates) and former Vice-Chair of the Czech Parliament’s foreign and defense committees during his time in opposition.

When asked about China by the media, Lipavský emphasized the human rights issues over business interests and called for closer relations with Taiwan. In April 2022, he met with Penpa Tsering, the leader of the Tibetan government-in-exile. Symbolically, he also opened a Prague exhibition of Badiucao, a Chinese political artist, despite a protest from the Chinese Embassy.

Yet, when it comes to the exit from the 16+1 format, the minister’s actions seem more wary. In mid-May, the parliament’s foreign affairs committee passed unanimously a resolution asking the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to explore ways of exiting from the 16+1 format. Needless to say, the minister does not need to be tasked by the parliament to contemplate leaving the format. Nor has the parliament any say in the Czech Republic’s decision to stay or leave. The format has a loose structure, so exiting would in practice mean stopping to show up at the 16+1 gatherings. But President Miloš Zeman might not be persuaded by a resolution of the parliament’s committee and if invited by the Chinese hosts, he may do as he pleases.

As Miloš Zeman’s second term comes to an end in March 2023, it appears more strategic for the government to simply wait for the president to leave the scene before setting a different course on China. The parliamentary committee’s resolution can be read as a safe way of introducing the topic of the 16+1 exit to the political arena, testing the reaction of the president, and signaling intentions to both the Czech allies and China.

The current political climate in the Czech Republic undoubtedly favors leaving the 16+1 format. It is no longer a question of whether the country should stay or leave, but when it goes. And the date is drawing near.

Written by

Ivana Karásková

ivana_karaskovaIvana Karásková, Ph.D., is a Founder and Lead of CHOICE & China Projects Lead at the Association for International Affairs (AMO) in Prague, Czech Republic. She is a an ex-Fulbright scholar at Columbia University, NYC, a member of Hybrid CoE in Helsinki and European China Policy Fellow at MERICS in Berlin. She advised the Vice-President of the European Commission, Věra Jourová, on Defense of Democracy Package.