The engagement of German cities with their Chinese partners has come under scrutiny recently. As cities like Kiel explore cooperation with China, questions arise about the balance between local economic interests and national security concerns.

In the first half of 2023, a revealing debate occupied the German press. The northern German port city and the state capital of Kiel had taken up talks with the northern Chinese port city of Qingdao to sign a partnership agreement. The contact between the two cities dates to 2006 when they signed a memorandum of understanding on increased cooperation in sailing sports. In the years that followed, Kiel sought closer ties with China in economic development and academic cooperation between Kiel’s Christian-Albrechts University and Chinese institutions. The city went so far as to pursue a dedicated city China strategy as part of its internationalization efforts.

Soon after the talks on the partnership agreement began, not only local politicians from the opposition conservative CDU party but also the Institute for Security Policy (ISPK) at Kiel University spoke out against the planned move. Critics focused primarily on the fact that both Kiel and Qingdao are important national centers for underwater naval warfare. On this basis, critics argued that the Chinese side could exploit the partnership agreement to facilitate the transfer of knowledge and technology to China and gain access to security-related information. As the situation made national headlines, federal politicians got involved and the local officials from the center-left SPD party ditched talks with Qingdao in mid-July.

Kiel certainly is not alone in Germany in its embrace of cooperation with Chinese counterparts. One only has to think of the Duisburg case, which revealed the risks of close relations with China in recent years. Since the relations of German municipalities with China repeatedly make headlines, it is worthwhile to evaluate their drivers and key trends.

State of Sino-German Municipal Engagement

As of now, 84 German cities cooperate with Chinese partners. Cooperation at the municipal level began in 1978 when Duisburg and the central Chinese city of Wuhan started building relations. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the development of subnational Sino-German relations accelerated at a rapid pace, with the latest additions in 2019. Currently, most German cities that carry political (e.g. Berlin as the federal capital), economic (e.g. Frankfurt am Main as the EU’s financial center), or military (Düsseldorf as the headquarters of important weapons manufacturers) significance cooperate with Chinese partners.

Municipal forging policy in Germany dates back to the 1950s, with the original goal of reconciliation in Europe. Consequently, the municipalities focused mainly on activities such as student exchange programs to foster international contacts and enhance intercultural understanding. More recently, activities such as administrative exchanges and the establishment of cultural, scientific, and business networks have also emerged. Starting in the late 1970s, the focus of German municipalities shifted from Europe to the Global South, where they increasingly engaged in humanitarian aid and development activities.

German municipal relations with China, on the other hand, were a special case from the beginning, as the case of Duisburg shows. The contact between Duisburg and Wuhan was established on the basis of the business interests of the Mannesmann, Krupp, and Thyssen companies, which were active in Wuhan at the time. Thus, in contrast to the municipal cooperation based on culture and humanitarian aid, Duisburg’s China ties developed with a focus on business and revolved around economic interests right from the start.

Most of the partnership agreements between German and Chinese municipalities were concluded around 2003. For Sino-German relations, the early 2000s were a particularly eventful period. Germany, then plagued by slow growth and high unemployment, had found in China an important economic partner to revive its economy. Consequently, then-Chancellor Gerhard Schröder (SPD) pursued a very China-friendly policy, which meant also siding with China in its disputes with the European Union, such as on the issue of the arms embargo. In the years that followed, the volume of German-Chinese trade multiplied, and the China business of German companies made the German economy much more resilient than its European counterparts in the crisis years after 2008.

After Schröder left office in 2005, former Chancellor Angela Merkel (CDU) largely continued Germany’s business-oriented China policy. It was not until the 2020s that public discourse on Germany’s China policy began to shift from a viewpoint focused purely on economic benefits and business opportunities to the inclusion of German security interests. It is this context that has driven the debate on the Kiel and Duisburg cases and the German-Chinese municipal cooperation in general.

German Business Interests vs. Chinese Geopolitical Strategy?

Most German municipalities share a similar challenge: A severe lack of resources leading to an investment backlog. Thus, city officials are always on the lookout to attract cash injections into the local economy, e.g. in the form of foreign investment. Considering this, engagement with partners in China offers plentiful economic opportunities. Thus, even as the federal government is adopting a more cautious approach in its China policy, German municipalities might have an entirely different set of interests.

This separation between the municipality and the federal government is supported by Article 32 (1) of the Basic Law (German constitution), which assigns responsibility for shaping foreign policy primarily to the federal level. Thus, municipalities are not allowed to formulate foreign policies that run counter to the political goals pursued at the federal level. However, because local governments often lack the staff and expertise to critically examine relations with China and the federal government does not micro-manage the policymaking of its local governments, there is no top-down control to make sure municipal and federal foreign policy is aligned.

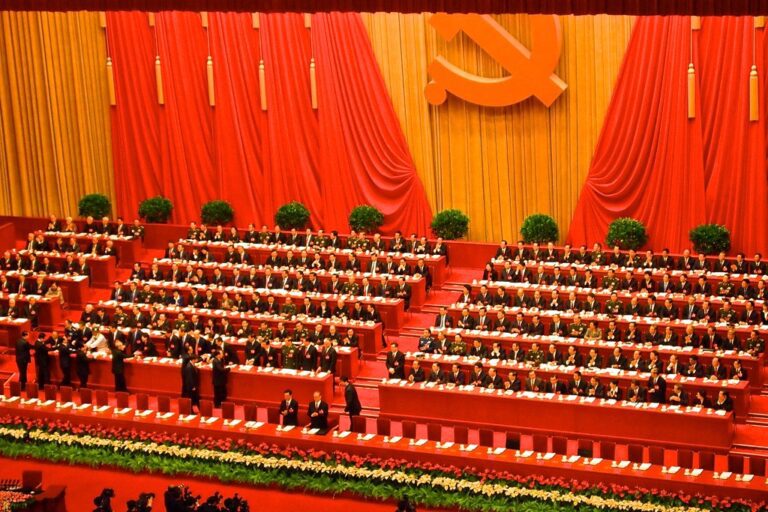

On the Chinese side, municipal cooperation is proactively promoted by Beijing as part of subnational diplomacy. Chinese regions and cities are actively approaching their European partners to complement the national level policy. In recent years, China has used the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as an instrument to attract German municipalities with economic benefits.

Sino-German inter-municipal relations are thus characterized by a strong asymmetry. First, Chinese cities and regions are much larger than their German counterparts. Second, China has a highly centralized system and municipal cooperation is geared toward a centralized Chinese foreign policy. The German landscape is much more decentralized. Third, there is a mismatch of interests, as the German side is primarily focused on economic benefits and business opportunities, while on the Chinese side, the promotion of national interests by the local actors plays a much more significant role.

In pursuing economic interests, foreign direct investment and projects under the BRI are used to expand China’s economic base, while cooperating with universities is employed to boost China’s quest for leading technology. To advance Chinese political interests, political actors at the subnational level, such as city majors, are pressured to conform to Chinese political demands, e.g., with the “One China” Policy. An important part of the Chinese strategy is to expand Chinese soft power through image control and narrative dominance. This is done, for example, by funding Confucius Institutes or cooperating in the field of sports on the local level.

Enhancing Municipal Capacities to Navigate a Multipolar World Order

Against this background, the question arises whether German municipalities should engage in cooperation with China at all. Within the context of the new German security strategy as well as the China strategy, there have been several proposals and initiatives urging German municipalities to be more circumspect in their dealings with China. In a similar vein, the federal government called on German universities to critically examine and ideally end their cooperation with Confucius Institutes, just as discussions around banning the use of Huawei technology in Germany’s push to catch up in digitalization are taking place.

However, the German government should refrain from excessive interference in local affairs, as Germany’s federal system must be respected. Moreover, cooperation with China should not be seen only from a security angle. China remains an important economic partner for Germany and improving international contacts and intercultural understanding via local connections remain an important task, especially in the emerging multipolar world order.

A better solution than introducing a top-down system is to define a common agenda, improve dialogue between the municipal and federal levels, and build municipal capacity. With the national security strategy and the China strategy, the federal government has taken major steps toward well-rounded German security and foreign policy. To achieve greater political coordination between the federal government and municipalities, the latter should be involved in setting the respective security policy agenda. When it comes to municipal interests, the municipalities must be heard in the policy-making process. Ideally, municipalities should be enabled to evaluate their international cooperation in light of the guidelines of German foreign policy and act accordingly on an independent basis. Funding and capacity building are needed to achieve this goal. Municipal officials, such as mayors, need to be trained in risk awareness and acquire foreign policy expertise to promote municipal resilience against hybrid threats, while continuing to work towards more international cooperation and intercultural understanding.

Written by

Tim Hildebrandt

Tim Hildebrandt is a Ph.D. candidate in political science and economics at the University of Duisburg-Essen and a Research Associate at the Ruhr West University of Applied Sciences. His research focuses on the intersection of politics, economics, and geography.