Education and student exchanges have long been central to the West’s engagement with China, with hundreds of thousands of Chinese students studying in Western institutions each year. In parallel, China has actively sought to engage overseas institutions and students through initiatives like Confucius Institutes (CIs). However, as tensions between the United States and China have intensified in recent years, suspicion toward academic collaboration with Beijing, particularly concerning the CIs, has grown. In response, China has initiated a rebranding exercise to mitigate rising concerns while shifting its focus to more receptive regions, including, to a certain extent, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and the Western Balkans.

Confucius Institutes function as nonprofit public institutions and are a flagship of China’s cultural soft power. The institutes are usually found at universities or colleges, nonprofit organizations, and occasionally at K-12 schools (i.e. the educational system that includes kindergarten, elementary, middle and high schools). The CIs are a collaborative initiative between a host institution, a Chinese organization (mainly universities), and, until recently, the Office of Chinese Language Council International (Hanban).

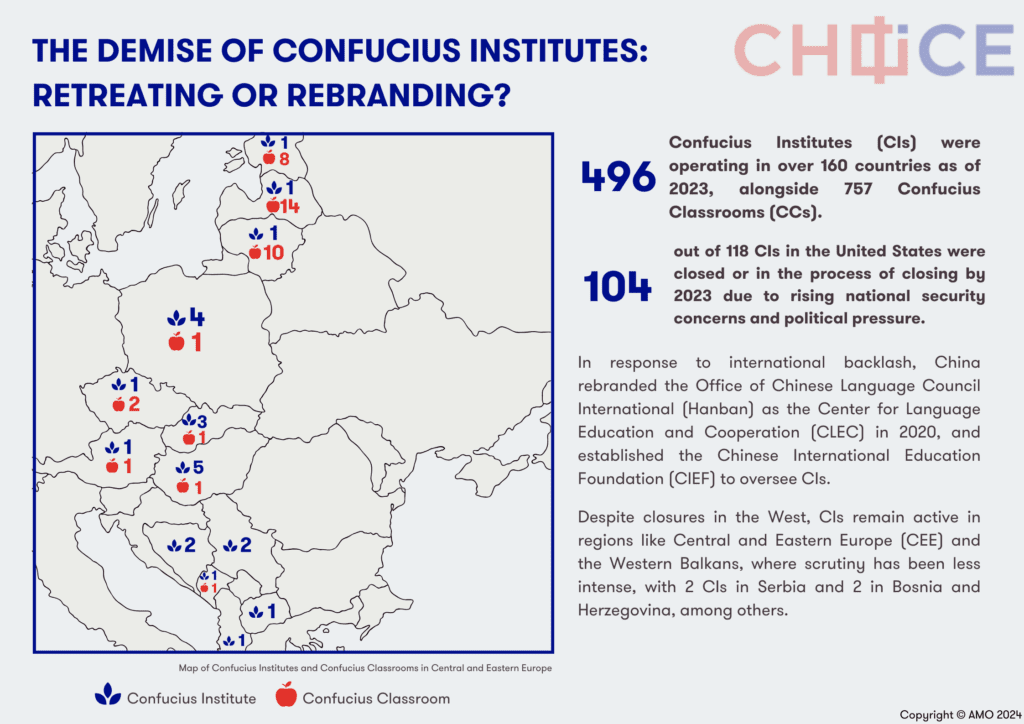

Since their inception, CIs have been operated and funded by Hanban, a branch of China’s Ministry of Education. The number of CIs worldwide has increased rapidly since 2004, with China aiming to set up 1,000 institutes by 2020. Though this goal has not materialized, by 2023, China had established and maintained 496 Confucius Institutes and 757 Confucius Classrooms (CCs) in over 160 countries.

However, following a series of scandals in the 2010s, Beijing has faced a global backlash over the alleged use of CIs as tools of Chinese propaganda. In recent years, growing national security concerns and fears of China’s influence campaigns penetrating host societieshave pushed the issue of Confucius Institutes higher up the political agenda.

Growing Suspicions

As tensions between the United States and China have intensified, CIs have faced growing criticism for their role in shaping the narrative through which China is depicted and perceived abroad. Accusations have surfaced that CIs censor discussions on issues sensitive to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), including the Tiananmen Square massacre, the Cultural Revolution, and human rights abuses in China, Tibet, and Taiwan.

Concerns have also mounted regarding the institutes’ alleged involvement in intellectual property theft, surveillance of Chinese and Hong Kong students, espionage, and the suppression of academic freedoms. A statement by Li Changchun, a former head of CCP propaganda, who in 2009 described CIs as “an important part of China’s overseas propaganda setup,” has fueled these fears and lent credibility to accusations that CIs are a tool of China’s propaganda apparatus.

The Crackdown Begins

The United States has led the charge against Confucius Institutes, with the Trump administration adopting a particularly hardline stance. During his tenure, President Trump signed a defense bill prohibiting the Department of Defense from funding Chinese language instruction by CIs or any institution hosting a CI.

In 2020, the State Department designated the Washington-based Confucius Institute US Center as a “foreign mission” of China, requiring the center to report its activities and operations to the US government. The Trump administration also pushed for colleges and universities to publicly disclose their financial ties and contracts with CIs, partly in response to a 2019 Senate subcommittee report revealing that nearly 70% of institutions receiving over $250,000 from Hanban had failed to report it to the federal government. Although the Biden administration later withdrew this proposal, Trump’s crackdown resulted in 104 of the 118 CIs in the US being shut down or in the process of closing by 2023.

Rebranding for Influence

Despite international efforts to close down Confucius Institutes, Beijing has found new ways to maintain its influence over educational institutions.According to a report by the National Association of Scholars (NAS), many of the 104 CIs that reportedly closed in the US have not entirely disappeared. Instead, most have either rebranded their CIs or entered into new agreements with their former Chinese partners, often replicating the original CI model with similar, if not identical, issues.

In mid-2020, in response to the growing international backlash and as part of China’s efforts to conceal CIs’ close connection to the government, Hanban rebrandeditself as the new Ministry of Education Center for Language Exchange and Cooperation (CLEC). It also established a nongovernmental organization, the Chinese International Education Foundation (CIEF), that now funds and oversees CIs including their replacements. CLEC is supervised by China’s Ministry of Education and receives funding from the Chinese government, thus remaining closely linked to the CCP.

The rebranding extended to the CIs themselves. NAS research indicates that many universities replaced their CIs with similar partnerships involving the same Chinese universities, opening new centers operated and staffed by the same personnel and funded by Hanban, now known as CLEC or CIEF. Some universities maintained existing CIs but relocated them to different host organizations, while others continued their partnerships with Chinese counterparts outside of the CI framework.

On a geopolitical level, education has traditionally served as a confidence-building measure between China and the United States, helping to manage tensions as their relationship ebbs and flows. A crackdown on educational cooperation, however, signals growing suspicion and escalating tensions. Notably, at the summit between US President Biden and Chinese leader Xi Jinping in San Francisco in November 2023, education cooperation featured prominently on the list of deliverables.

Yet, while much of the experts’ and politicians’ attention has centered on the closure of Confucius Institutes in the West and China’s superficial rebranding efforts, Beijing has increasingly redirected its focus to more receptive regions. This strategic shift includes expanding influence in countries across Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East.

Zooming In on the Western Balkans

Unlike the United States and other parts of Europe, the situation across CEE and the Western Balkans remains more varied but relatively stable, with no significant changes in the number of Confucius Institutes (CIs). Furthermore, public debate in these regions has largely avoided the controversies surrounding the institutes that have emerged elsewhere.

In the Western Balkans, CIs remain active in all countries except Kosovo, which China perceives as “an autonomous province” under Serbian sovereignty. Serbia hosts two CIs, primarily offering Mandarin classes. Since 2011, Mandarin has been available as an elective subject in over 60 public schools, and some language schools now teach it as a compulsory subject, with Beijing funding scholarships for those demonstrating proficiency.

Bosnia and Herzegovina hosts two CIs, one in Sarajevo and another in Banja Luka. The internal divide between the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, based in Sarajevo, and the Republika Srpska, based in Banja Luka, provides China with opportunities to exploit these divisions in implementing its soft power strategies. Of the two, the CI in Banja Luka appears to be more active.

In Montenegro, China’s soft power has gained significant traction despite operating only one CI and one CC. In 2019, the CI’s courses attracted 5,000 participants, including over 100 civil servants who took part in exchange programs—a notable success for China. Conversely, in North Macedonia, Beijing’s soft power seems less successful, with only one CI established and little public interest. However, those who participate in CI exchanges may eventually become key decision-makers, potentially influencing the country’s China policy.

Lastly, Albaniaopened its first and only CI in 2013, but China’s soft power efforts there have been less effective. The success of these efforts has largely depended on cooperation agreements with Albanian media, and overall, Beijing’s influence seems to remain limited as Albania continues to align itself with Western-oriented goals, aspiring for deeper integration into Western-led security and economic frameworks.

Suspicion in CEE countries

In the Baltic states, each country hosts one CI, with CCs operating in 10 Lithuanian, 8 Estonian, and 14 Latvian schools.

Although still active, CIs have come under increased scrutiny in these countries following the release of the NAS report. In February 2019, Lithuania’s annual national threat assessment highlighted China’s influence operations, particularly regarding sensitive issues like Tibet and Taiwan. Latvia’s security services have also identified potential intelligence risks associated with CIs, while Estonia’s intelligence services, though initially muted, raised similar concerns in their 2021 International Security and Estoniareport, emphasizing that”the rebranding of CIs did not mitigate the security threats they pose.”

In Slovenia, China opened one CI in 2010 and a CC in 2022. It has seen a largely positive reception for its CI, particularly at the School of Economics and Business, where it serves as a hub for academic and business communities by organizing cultural and business events.

Meanwhile, Hungary has expanded its CI presence, largely due to the lack of scrutiny and PM Viktor Orbán’s favorable relationship with Beijing, with the country opening its fifth CI in 2019 and continuing to host one CC.Slovakia still operates three CIs and one CC, despite growing concerns among experts and academics about Beijing’s influence and propaganda activities in Slovak universities.

In contrast, Poland and the Czech Republic have begun cracking down on CIs. Poland closed two of its six CIs between 2022 and 2024, and the Czech Republic shut down one of its two CIs in 2023. However, the impact of these closures remains unclear. Similar to the findings in the NAS report, Czechia’s Palacky University terminated its CI contract but replaced it with a different agreement with Beijing Foreign Studies University, a key institution behind CIs in Europe. Additionally, two CCs continue to operate in Czechia and one in Poland. This continues to be the case despite the Ministry of Interior’sand civil society organizations’ continuous effortsto protect the Czech academic community from falling into the traps of China’s malign influence.

Overall, while concerns about China’s influence on academic institutions are rising globally, CEE and the Western Balkans have been slower to implement thorough crackdowns on Confucius Institutes. The issue has arguably attracted less attention in these regions compared to other parts of Europe, such as Sweden, which had closed all its CIs and CCs by 2020.

The Future of Confucius Institutes

Despite appearing to retreat from public view, the rebranding of Confucius Institutes is making their network more decentralized, complicating governments’ efforts to monitor their activities and funding, continuing to pose a threat to host countries.

Although the US has led the crackdown, Confucius Institutes continue to thrive in other regions, including the Middle East, Africa, and Southeast Asia. In regions like the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), high levels of Chinese investment, trade, development aid, and the accessibility and affordability of Chinese goods have tilted local perceptions in Beijing’s favor. Southeast Asian countries, too, are less likely to criticize or alienate China, prioritizing the protection of their interests. Additionally, for many in the Global South, learning the Chinese language and culture is seen as a pathway to economic growth and prosperity, with China viewed as a successful model, despite its non-democratic governance.

As geopolitical realities shift and China’s relations with the West become increasingly strained, the West will likely continue to monitor, scrutinize, and limit Chinese-led initiatives, including Confucius Institutes, whether rebranded or not. Consequently, China’s soft power efforts may increasingly target regions where local populations are more receptive to the Chinese narrative, and where governments are prioritizing economic gains rather than security concerns.

Written by

Dominika Urhová

DUrhovaDominika Urhová is a China Analyst at AMO, specializing in China's foreign policy, Cross-Strait relations and China's influence in the Middle East and the Western Balkans. In the past, she contributed to the Middle East Policy Journal and to the research outputs of the Observer Research Foundation. Dominika holds a Master's degree in Security Studies and Diplomacy from Tel Aviv University and a Bachelor's degree in Development Studies with a concentration in Economic Development from Lund University in Sweden.