Recycling: A Pothole in the Great Sino-European Electric Vehicle Race

Electric vehicles are becoming a hot-button issue in EU-China ties. Next to component manufacturing and supply chain stability, there is a third critical component of the electric vehicle competition: recycling.

This article is part of a series of articles authored by young, aspiring China scholars under the Future CHOICE initiative.

Last month, in her State of the EU (SOTEU) address, President Ursula von der Leyen announced an anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese electric vehicles (EVs) entering the EU market, citing increasing European concerns about China’s growing presence in the sector. Chinese EVs, buoyed by substantial government subsidies and easier access to critical materials for their production, are on average €10,000 cheaper than their European counterparts. China has expressed its dissatisfaction with the investigation, asserting it lacks adequate evidence and contravenes World Trade Organization Rules.

Among EU Member States, reactions vary, with some, chiefly France, already implementing similar national policies, while others, such as Germany, have shown more reticence, given the vulnerability of their automakers to potential Chinese retaliations.

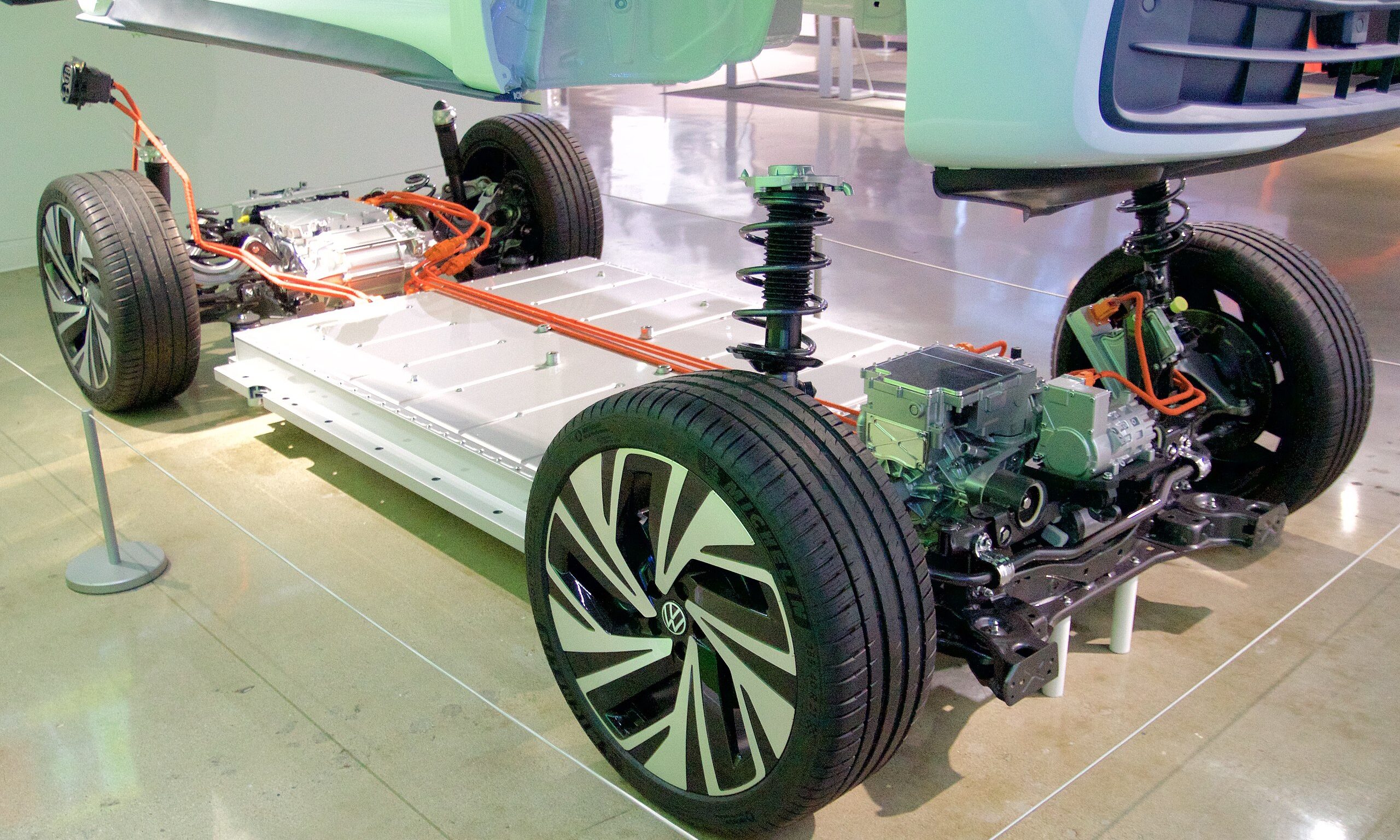

Sino-European tensions over EVs have prompted discussion around EV development and manufacturing policies. Recycling, a critical aspect of achieving electric vehicle strategic autonomy, emerges as a third dimension. Ensuring EV circularity is increasingly seen as crucial for environmental transition programs such as the EU Green Deal, as well as a way to reduce the cost of EVs and foster penetration in markets across the world. Most EV components, such as polymers, metal and electric parts, can be processed using existing recycling systems, but other components such as batteries and the critical metals they contain, are sparking recycling revolutions. How have the EU and China tackled the recycling challenge?

Fuelling Recycling: General Policy Frameworks

The EU has been a first mover in the area of regulation of recycling. The EU’s end-of-life (EOL) vehicle framework, based on Directive 2000/53/EC introduced in 2000, seeks to impose reusing and recycling quotas on materials and to limit, if not avoid, the use of hazardous materials in the manufacturing of vehicles. The set quotas were rather ambitious: manufacturers were required to ensure that at least 85 percent of a new vehicle’s weight was reusable and/or recoverable and that 80% of its weight was reusable and/or recyclable. These quotas were raised in 2015 to 95 percent and 85 percent respectively. This framework has seen limited evolution over two decades, although an instrument was passed in 2023 to allow exceptions on some hazardous materials to be used in specific cases.

A new Regulation, proposed by the EU Commission in July 2023 aims to rectify four overarching problems of current EOL policy: the lack of integration between circularity and production, sub-optimal treatment of materials vis-a-vis their potential contributions, the outsourcing of recycling processes to third countries with more lenient environmental standards, and the absence of further policy outside the current framework which is limited to passenger vehicles and trucks under 3.5 tonnes. The main benefits of the new Regulation are supposed to be environmental, as it is expected to reduce CO2 emissions by 12.3 million tons by 2035, as well as contribute to the resilience of the automotive sector and lead to “long-term energy savings.”

Moving from Brussels to Beijing, China’s approach to EV recycling has primarily been directed by the government to stimulate EV adoption, meet decarbonization targets, reduce reliance on imports of key metals, and tackle long-term critical material price challenges.

China’s main EV framework includes two plans for 2012-2020 and 2021-2035, but lacks explicit references to recycling. The 2018 Guiding Opinion on Accelerating the Promotion and Application of New Energy Vehicles included a single commitment to promote recycling of EV batteries by developing policies and establishing an ad-hoc system, but did not mention recycling efforts for other EV components. Further recycling guidelines and policies have been published on a component-specific basis, with EV batteries receiving particular attention.

All Roads Lead to Recycling Batteries

EV battery recycling has largely been hindered by three obstacles. First, battery collection schemes are largely inefficient or even nonexistent. Second, the process of dismantling the battery to retrieve its components is very expensive. Third, because of the aforementioned reasons, there are only small amounts of materials that can be recycled, which is seen as insufficient to warrant the necessary investment in recycling facilities.

When it comes to collection, both the EU and China attribute the responsibility to the car manufacturers. The Chinese Provisional Measures refer to national standard WB/T 1061-2016, which outlines the responsibilities of automakers but sets no specific collection standards. The previous EU battery directive did set concrete targets for the collection, but the newly approved one lacks targets for EV batteries, indicating that specific targets should be set via a review clause after the collection rate calculation methodology is defined. Thus, at their current stage, both policies lack enforceable battery collection standards, leaving it instead to automakers.

Regarding battery dismantling, both the EU and Chinese regulation attribute the responsibility for covering the costs to EV producers. They also highlight metals of particular interest, with the EU Directive providing specific targets for a few. The Chinese policy does not, instead repeatedly emphasizing that manufacturers should provide tracing and dismantling information to simplify the disassembly of EOL batteries into their components.

However, this approach is limited, as the Chinese recycling industry is bifurcated into a small group of whitelisted companies with enormous recycling capacity, and a myriad of informal, illegal workshops, that often do not uphold environmental standards. By processing materials in the informal market, these workshops deprive the central government of important resources that can be reused for the production of EVs.

The EU and Chinese policies differ in their approach to the issue of investment in recycling. The EU directive argues that a more stable regulatory framework will lead to an increase in investment certainty. While the Chinese policy does not mention the topic of investment in recycling facilities, actual investment in EV battery recycling has recently risen, whereas in the EU most investments still focus on battery-making facilities.

Putting the Pedal to the Metal: Recycling Critical Minerals and REs

A shared key driver in the recycling of EV batteries, engines, and other components is securing a supply of critical minerals they contain. Critical mineral policies around the globe pay particular attention to cobalt, lithium, nickel, and manganese, which are found in EV batteries, platinum used in fuel cells, and rare earths in engines and some types of batteries.

The recently proposed EU Critical Raw Materials Act promotes recycling as one of the pillars of the bloc‘s strategy to reduce critical raw material (CRM) dependency, setting a goal of 15 percent of the EU’s annual consumption of CRMs coming from recycling by 2030, as well as introducing requirements to track the amount of recycled CRMs contained in EV components.

On the Chinese side, mineral security was elevated to a national strategic issue for the first time in the 2021-2025 National Security Strategy, an expected development given China’s heavy dependance on lithium, cobalt and nickel imports to produce EV batteries. However, larger mineral companies in China have acknowledged that while recycling is projected to gain weight in the industry over time, it is unlikely to substantially replace mining in the short term.

Is Anyone Winning the Recycling Race?

Current trends, not the least of which is the securitization of EV policies, signal that recycling will likely become a key policy focus for both the EU and China. Both parties are in the process of developing structured systems to recover precious materials through circularity to reduce resource dependency and enhance environmental benefits.

Whether and to what extent recycling can contribute to these goals in the EU remains a significant unknown. While the plans on the table align with current environmental objectives, their capacity to autonomously support the EU’s EV production is uncertain. Additionally, concerns have been raised regarding whether the increasing emphasis on security in policies fostering EV component recycling could impinge on its environmental benefits.

The implications for EU-China relations and the ongoing EV investigation are unclear. On one hand, reducing dependency may mitigate the EU’s previous concerns about China being a ‘security threat.’ Considering the current over-reliance on Chinese materials and technology, an embargo or an export restriction, such as what happened with Japan in 2010, would have a considerable impact on the EU EV industry.

All things considered, recycling is a path that the EU could follow to lessen its dependency on Chinese materials, especially given that the Union seems, at least on paper, to be a few steps ahead in the race in policy development in this particular area. However, it remains to be seen whether EU efforts will prove to be sufficient or not and, in any case, China still retains its predominance in key sectors such as critical raw material extraction and processing, making the Union a challenger rather than a leader of the EV sector.

Written by

Valeria Fappani

choooseurnameValeria Fappani is a PhD student at the School of International Studies of the University of Trento researching EU-China relations from a comparative law perspective. Her research interests include business due diligence and corporate social responsibility, micro-level analysis of Chinese laws and policies, and EU-China trade and FDI relations. She also has extensively participated in and engaged with youth-led initiatives about the EU, China and their relations.

Blanca Marabini San Martín

BlancaMSMBlanca Marabini San Martín is a PhD student at the Centre for East Asian Studies of the Madrid Autonomous University (CEAO – UAM), in Spain, as well as part of the China Horizons Research Consortium. She has collaborated with the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS, Leiden), the Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies (Ministry of Defense of Spain), and the Spanish Chinese Policy Observatory. Her research interests center around the climate, environmental, and green tech dimensions of China’s foreign policy, particularly within the framework of EU-China relations.