This article was originally published with Taiwan Insight and is republished here with the permission of the author. The article is part of an ongoing collaboration between Taiwan Insight and CHOICE.

The automotive heartland of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) stands at a crossroads. As Chinese battery and electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers increasingly localise their production in the Visegrád Four (V4) states – Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, and, to a lesser extent, Czechia – these countries are witnessing a surge in investment that advances their green and digital transitions while simultaneously raising concerns about European competitiveness, strategic autonomy, and local value creation. In contrast, the construction of a semiconductor foundry in neighbouring Germany – majority-owned by Taiwan’s TSMC – appears more closely aligned with the EU’s goal of technological sovereignty and its broader de-risking agenda.

The region thus faces a fundamental question: will it remain locked in the role of an automotive assembly line, or can it finally break free from its semi-peripheral status? The answer lies not only in the factories being built but also in understanding how global production networks and value chains shape the foreign policy options available to small states and middle powers – and how Taiwan’s chip diplomacy may offer an unexpected pathway forward, especially if it succeeds in integrating the very supplier networks strained by the EV transition and the influx of Chinese capital.

Vanguards and Outliers

Since 2019, when Ursula von der Leyen became President of the European Commission, declaring the geopolitical nature of her first College of Commissioners, there have been several shifts – though largely rhetorical – in EU-China and EU-Taiwan relations. Many of these were preceded, if not spurred, by developments in CEE-China and CEE-Taiwan relations. A notable example is the European Commission’s 2022 request for WTO consultations with China, prompted by Beijing’s economic coercion of Lithuania. At the same time, it was preceded by the adoption of key trade defence tools, such as the Foreign Subsidies Regulation, the Anti-Coercion Instrument, and the International Procurement Instrument, reflecting the EU’s evolving view of the intersection between economic policy and security. China’s sanctions on Lithuania were themselves triggered by the opening of the Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius, which came shortly after Lithuania’s withdrawal from what in its earliest form was known as the 16+1 framework of cooperation between China and CEE.

Post-COVID 19 relations between China, Taiwan, and CEE have been marked by two major developments. First, CEE countries once criticised for their ties to China have become vocal critics of the EU’s China policy, which – contrary to claims of a paradigm shift – remains largely issue-specific rather than holistic. Second, several CEE states have begun pursuing closer ties with Taiwan, especially Czechia, Lithuania, Poland, and Slovakia, which have emerged as ‘vanguards’ in not just CEE’s but the EU’s political and economic engagement with Taiwan. Hungary, on the other hand, emerged as the main V4 outlier, and is often regarded – alongside Serbia – as Beijing’s closest European partner. With both Lithuania and Czechia electing governments that pledged to pursue values-based foreign policies, political elites in these two countries have acted as ‘norm entrepreneurs’ at the EU level, pushing for more substantive changes in the bloc’s China and Taiwan policies.

Chinese Greenfield Investment Influx

Hungary has become Europe’s top destination for Chinese EV investment, attracting 44 percent of all Chinese FDI in Europe in 2023. CATL’s €7.3 billion battery plant in Debrecen and BYD’s €5 billion EV assembly facility in Szeged are the largest Chinese greenfield investments not only in Hungary but in the entire region. At first glance, this influx appears to align with the ambitions of the European Green Deal, helping CEE countries transition from internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) to electric mobility. Yet, beneath the surface, a troubling pattern emerges: most Chinese investments focus on low-value assembly operations, with inputs largely imported from China.

This model mirrors that established by German automakers that have dominated the region since the 1990s – characterized by limited technology and knowledge transfer – but with Chinese industrial strategies and broader (geo)strategic goals making it even more pronounced. The result is a deepening of the region’s semi-peripheral (or rather ‘integrated periphery’) status, with the V4 continuing to produce finished vehicles for export while remaining dependent on Chinese suppliers for the most valuable components. Compounding this, most regional employment is concentrated in component manufacturing – a sector already threatened by the EV transition, as EVs require fewer parts than ICEVs.

The Chip Opportunity

Enter Taiwan’s TSMC and its €10 billion foundry in Dresden – a potential game-changer for regional dynamics. While Czech (and other V4) officials initially expressed disappointment with the decision to locate the plant in Germany, its focus on automotive chip production creates several opportunities for CEE suppliers. Unlike the headline-grabbing 2-3nm chips, automotive semiconductors rely on older ‘legacy’ technologies – an area where European firms like Infineon, NXP, and Bosch (each holding a 10 percent stake in the foundry) excel.

Not only do Chinese EVs themselves remain reliant on European automotive chip suppliers, but this investment aligns closely with the EU’s de-risking and strategic autonomy agendas – particularly the Chips Act, which seeks to double the EU’s share of global semiconductor production from 10 percent to 20 percent by 2030. It also opens new avenues for industrial upgrading in the V4, where the automotive component suppliers are already deeply embedded in German production networks.

While Czechia has attracted far fewer (low-value) Chinese investments than its neighbours, it is particularly well positioned to benefit from (high-value) Taiwanese investments tied to the German semiconductor hub. There is already a robust R&D cooperation in semiconductors between Czech universities and Taiwanese companies (including TSMC). Initiatives such as the Chip Academy at the Czech Technical University in Prague, the Advanced Chip Design and Research Centre in Brno, and the Supply Chain Resilience Centre at Charles University highlight this synergy at an institutional level. Czechia is also increasingly emerging as a tech innovation hub within the EU, with several of its companies, such as Braiins (developer of cryptocurrency mining chips) and Advacam (designer and manufacturer of radiation detection sensors, including for space exploration) being both TSMC customers and major contributors to the bloc’s efforts to build Europe-wide semiconductor supply chains. Foreign firms like Analog Bits, which designs and develops mixed-signal IP blocs, also maintain (high-value) operations in the country.

Between Global Structures and Local Elites

The V4 countries’ differing responses to Chinese and Taiwanese investments illustrate how geo-economic structures – particularly state positions within macro-regional and global value chains – interact with elite agency in shaping foreign policy. Hungary under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has fully embraced Chinese investment as part of his Eastern Opening Policy, treating economic pragmatism as paramount regardless of geopolitical concerns. The government’s National Battery Industry Strategy 2030 does little to alter Hungary’s semi-peripheral position in global value chains or reduce its dependence on foreign capital. This approach runs counter to the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda and constrains domestic efforts to foster industrial upgrading, as it effectively limits opportunities for value chain transformation to geopolitical or structural shifts; the former induced by the broader external environment and the latter by foreign firms and multinational corporations in host countries.

By contrast, Czechia under Prime Minister Petr Fiala has adopted a values-based foreign policy that prioritizes ties with Taiwan and other democratic partners over engagement with China – even at the expense of short-term economic gains. While this approach could change after the October general election, precedent suggests that any reversal would be limited. Former Prime Minister Andrej Babiš, whose party currently leads the polls, was more accommodating of China than Fiala but still more cautious than his counterparts in Hungary and Slovakia.

These diverging approaches underscore how the integrated periphery status of the V4 can be either passively accepted or strategically leveraged, especially when it comes to Taiwanese actors – particularly those involved in the country’s chip diplomacy – who see the region as an entry point for deeper engagement with both CEE and the EU. Nonetheless, Taiwanese elites face several challenges of their own. Chief among these are labour shortages and a lack of skilled workers – factors that have already affected the TSMC’s projects in Japan and the United States.

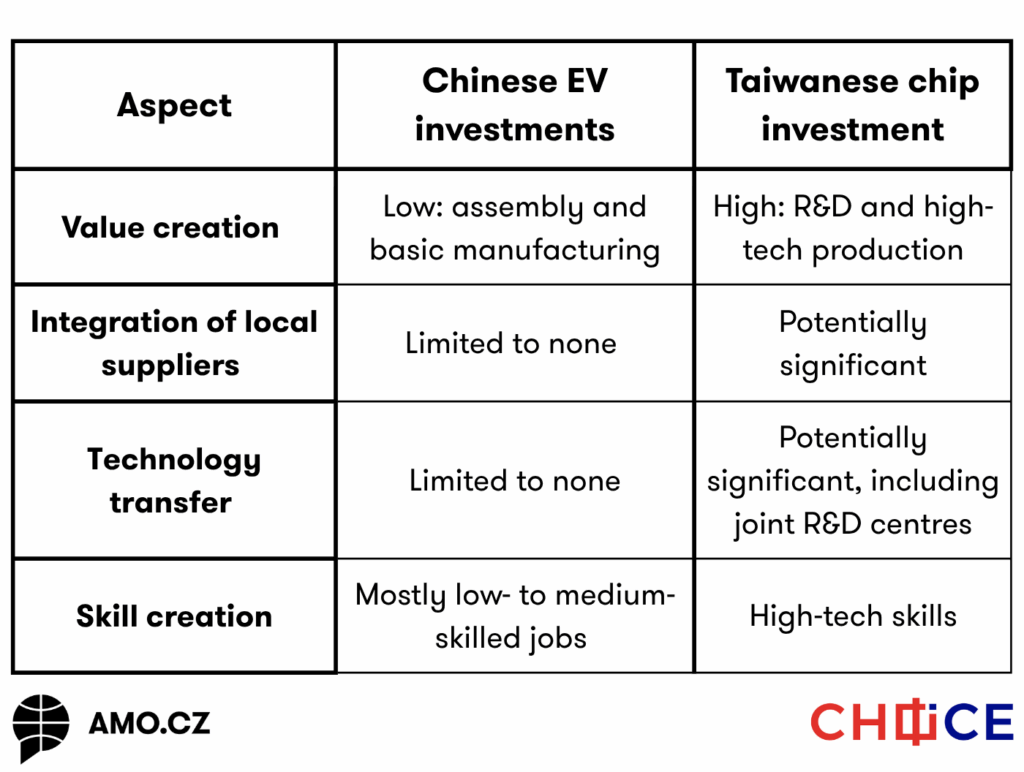

In response, the Taiwanese government is increasing the number of semiconductor scholarships available to Czech students. This focus on R&D collaboration (and thus potential technology transfer) and human development is precisely what distinguishes Taiwanese investments from their Chinese counterparts and enhances their potential to drive (or at least contribute toward) industrial upgrading in the V4 states (see Table 1). Another challenge is the misalignment between the interests of political and economic elites. Taiwanese firms’ investment decisions are not necessarily driven by political considerations (or diplomatic goals), as evidenced by Hungary’s long-held position as the leading V4 recipient of Taiwanese FDI. This disconnect, however, may be narrowing, as shown by the increasingly deep engagement between the two countries’ political elites and the newly announced investments that imply a growing synergy between political objectives and economic realities in Taiwan’s engagement with Czechia.

Table 1: Potential contributions of Chinese and Taiwanese investments to the V4

The Way Forward

Three key insights emerge from this intersection of (geo)economics and (geo)politics. First, CEE countries’ positions in global value chains significantly constrain their foreign policy options – yet agency, though limited, still matters. Czechia’s values-based approach entails short-term costs but creates space for strategic opportunities, which, while also available to its more pragmatic neighbours, are constrained by the pro-China orientation of their political elites (and, in the case of Hungary, also the increasing convergence between the interests of its political and economic elites). Second, Taiwan’s chip diplomacy offers potential for capability upgrading in CEE – provided it is backed by sustained R&D cooperation and human capital development. Scholarship programs and research partnerships may prove more transformative than factory announcements.

Third, the broader implications extend beyond individual investments to the region’s industrial future. CEE countries that succeed in attracting high-value semiconductor activity could position themselves as critical nodes in global technology supply chains. Those that remain focused on low-value automotive assembly risk being squeezed between US-Chinese competition (especially the former’s technology and the latter’s critical mineral controls) and Germany’s slow automation.

The automotive transformation in Central Europe is far from over. Whether the region escapes its semi-peripheral status or becomes even more dependent on external actors will depend largely on strategic choices made by its political and economic elites in the coming years. The intersection of Chinese EVs and Taiwanese chips offers both risks and opportunities – the challenge for CEE is to seize the latter while avoiding the former.

Written by

Dominika Remžová

DominikaRemzovaDominika Remžová is a China Analyst at AMO, specializing in Chinese economy and industrial policy, supply chains, critical raw materials, electric vehicles and, more generally, Chinese foreign policy. In the past, she contributed to Taiwan Insight and The Diplomat, among others. Dominika is pursuing her PhD in Political Science and International Relations at the University of Nottingham. She earned her Master's degree in Taiwan Studies from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London and her Bachelor's degree in Chinese Studies from the University of Manchester.