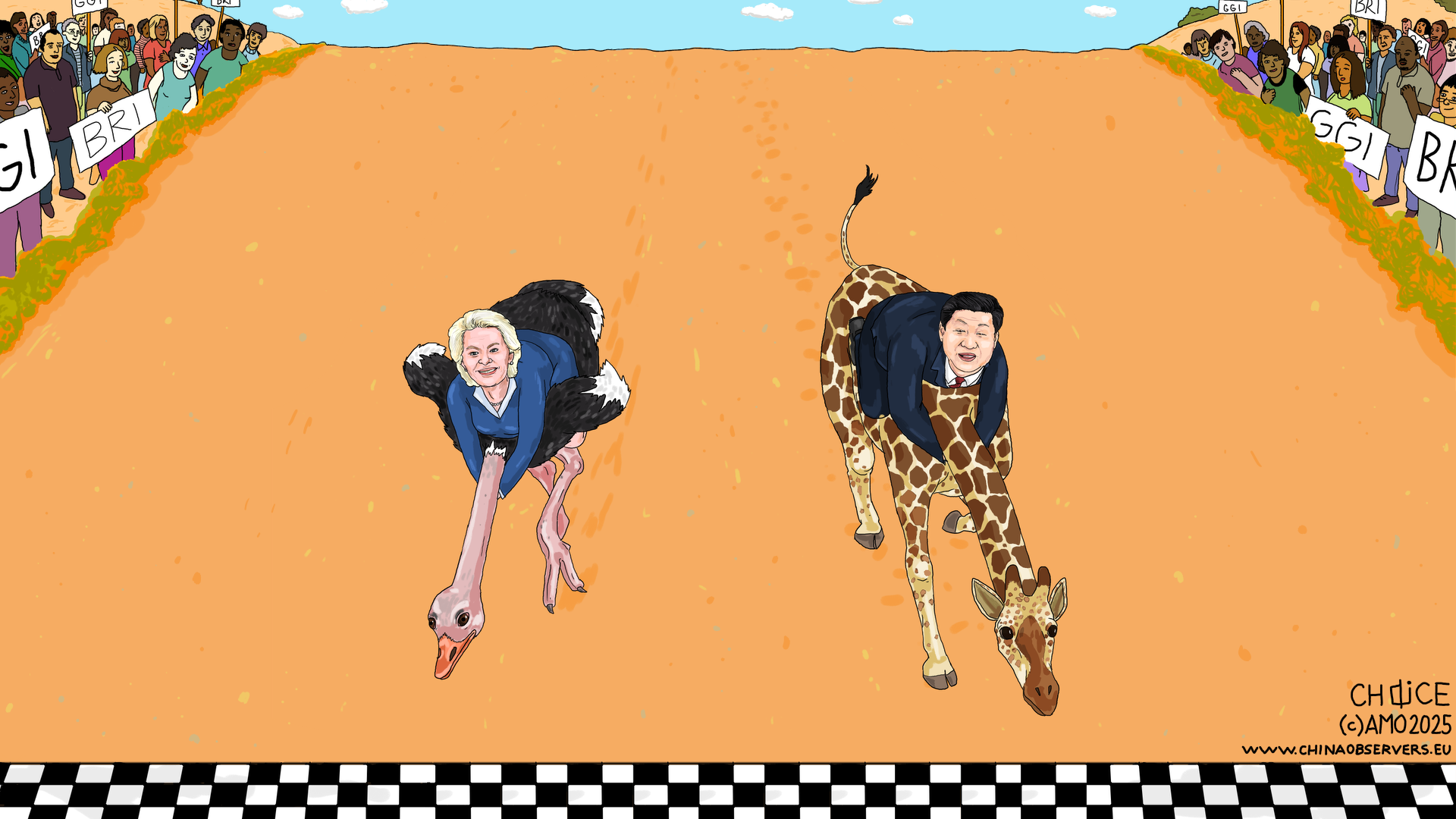

Poor Man’s BRI: The Global Gateway as a Strategic Tool?

This article is based on the research paper “Leveraging the Global Gateway Initiative to Advance the Czech Republic’s Strategic Interests” by Dominika Urhová, published by the Association for International Affairs (AMO) in March 2025.

In recent years, global geopolitical shifts – including China’s rise and escalating US-China competition – have prompted the EU to reassess its strategic stance, leading to a greater focus on strategic autonomy and diversifying partnerships. As part of this ambition to expand the EU’s global influence, the Global Gateway Initiative (GGI), a large-scale infrastructure investment strategy, was unveiled in 2021. However, while the EU has set ambitious goals, the initiative’s success will largely depend on effective implementation and leadership. In this context, the recent appointment of Jozef Síkela as EU Commissioner for International Partnerships positions the Czech Republic to play a pivotal role in bringing the GGI to fruition.

EU officials have yet to explicitly frame Global Gateway as a competitor or response to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Nonetheless, several parallels between the two initiatives, along with comments from EU officials like Ursula von der Leyen have led to the GGI being increasingly seen as a counterbalance to China’s expanding global influence. The GGI can also be seen as part of a broader and relatively recent global effort to counter the BRI, which has allowed Beijing to gain a significant foothold in various regions. This global effort has resulted in a surge of infrastructure initiatives, including the US-spearheaded Build Back Better World and the UK’s Clean, Green Initiative. Collectively, these efforts not only demonstrate the renewed commitment of the US, EU, and allied nations to addressing global challenges and reducing the widening global infrastructure investment gap but also to establishing themselves as a preferred alternative to the BRI.

It’s All About China, Stupid

While not directly stated, the wording in the GGI description reflects the EU’s ambition to be recognized as the leading partner for nations struggling with inadequate infrastructure and the widening global investment gap. Additionally, the Joint Communication from December 2021 begins by emphasizing democracies, their values, and their responsibility to address global challenges, positioning Global Gateway at the heart of today’s geopolitical landscape. This framing subtly suggests that the GGI is designed to serve as a credible alternative to China’s BRI, addressing its shortcomings and avoiding its associated pitfalls. The narrative surrounding the Global Gateway also highlights the EU’s need to strengthen its global presence and competitiveness, particularly in infrastructure development – a sector heavily influenced by China since 2013. As a result, it is difficult, if not impossible, to analyze the GGI without referencing the BRI or drawing comparisons between the two initiatives.

The GGI’s geopolitical relevance was further underscored by a leaked briefing intended for Jozef Síkela, the new Commissioner for International Partnerships. The document highlighted the EU’s need to strengthen its ties with emerging and developing economies, referencing a “battle of offers” and portraying the GGI as a tool for both defensive and offensive geopolitical objectives. The competitive undertones of the GGI were also evident in Ursula von der Leyen’s 2023 speech at the inaugural Global Gateway Forum. Without explicitly naming China, she criticized the exploitative practices of other global actors and emphasized the EU’s goal of offering sustainable and transparent investment choices. Former Commissioner Jutta Urpilainen similarly highlighted the “battle of narratives” surrounding global infrastructure investments and China’s ability to deliver tangible outcomes. These statements place the GGI at the center of shifting geopolitical dynamics, underscoring its importance in the EU’s efforts to enhance its global stature and competitiveness.

Síkela’s (Gate)Way Forward

The International Partnerships portfolio presents the Czech Republic with a significant opportunity to shape the EU’s strategic agenda. This portfolio is increasingly recognized as a cornerstone of the EU’s evolving foreign policy, which seeks to integrate economic priorities with geopolitical ambitions.

Overall, the appointment of Síkela as the new EU Commissioner for International Partnerships has the potential to elevate the Czech Republic’s image and influence within the EU. Given the scope of the portfolio and the GGI, the Commissioner will likely be involved in strategies related to artificial intelligence, healthcare, energy security, climate, and transportation. A tangible progress in GGI projects under Síkela’s leadership could thus enhance the Czech Republic’s visibility on both EU and international stages.

A key component of the GGI is its Europe-Africa Investment Package. Around half of the total GGI budget of €300 billion has been allocated to projects in Africa. The continent’s vast resource base, rapidly growing population, and developmental needs offer significant opportunities for the GGI to drive transformative change while securing access to critical raw materials (CRMs) and enhancing the EU’s geopolitical footprint. However, while the EU-Africa Investment Package plays a central role in the Global Gateway Initiative, the continent presents unique challenges for the EU. These stem from the historical legacy of exploitative and one-sided relationships established during the colonial and post-colonial periods.

Against this backdrop, the Czech Republic’s past collaborations with African nations create a solid foundation for future engagement with the region, giving Prague a stronger position than many other EU member states to rebuild trust with African countries and elevate mutual cooperation to a new level. During the Cold War, Czechoslovakia was among the most engaged socialist countries on the continent. What is more, unlike many other EU nations, the Czech Republic does not carry the weight of a colonial past. The country is also increasingly regarded as a reliable development partner that understands the specific needs of different African countries and can offer practical, affordable, and high-quality solutions. Moreover, the Czech Republic has also cultivated a reputation for foresting mutual relations based on equal partnerships, free from neo-colonial ambitions.

A Gateway to Influence or a Roadblock?

The GGI represents the EU’s ambition to influence global infrastructure investment and counteract China’s growing presence. However, for the initiative to succeed as a viable alternative to the BRI, it requires more than financial backing and strategic framing – it demands effective implementation, strong partnerships, and a distinct geopolitical vision.

The selection of Jozef Síkela as the EU Commissioner for International Partnerships brings both opportunities and challenges. If leveraged effectively, his position could enhance the EU’s global standing and boost the Czech Republic’s diplomatic and economic presence. Focusing on Africa as a major investment area reflects the EU’s broader strategic goals while revealing ongoing geopolitical tensions, especially in regions wary of Western involvement.

Ultimately, the GGI is more than just a mere infrastructure initiative – it is a test of Europe’s ability to navigate intensifying geopolitical rivalries. Should the EU fail to deliver tangible results, the GGI may be dismissed as yet another ambitious plan lacking substantial impact. Conversely, if executed with precision, transparency, and adaptability, the initiative could signify a pivotal moment for the EU’s global influence, demonstrating its ability to shape the future of global development rather than merely responding to China.

Written by

Dominika Urhová

DUrhovaDominika Urhová is a China Analyst at AMO, specializing in China's foreign policy, Cross-Strait relations and China's influence in the Middle East and the Western Balkans. In the past, she contributed to the Middle East Policy Journal and to the research outputs of the Observer Research Foundation. Dominika holds a Master's degree in Security Studies and Diplomacy from Tel Aviv University and a Bachelor's degree in Development Studies with a concentration in Economic Development from Lund University in Sweden.