This article is based on the research paper “The Cost of Going Green: Chinese EVs and Their Local Impact in Slovakia” by Dominika Remžová, published by the Association for International Affairs (AMO) in June 2025.

As the V4 states continue to attract Chinese electric vehicle and battery investments, differences are emerging between the interests of national elites and local communities chosen to host these manufacturing (and recycling) facilities. This can be seen in the case of local opposition in the small Slovak town of Šurany, which was selected to host a major battery production facility as part of a broader industrial park complex. With the opposition group’s environmental and social concerns echoing patterns seen across similar protests in Hungary, it is important to understand these “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) sentiments, which highlight the complex task of balancing economic growth and the green transition while upholding democratic principles such as public consultations.

The battery protests reflect Slovakia’s (and more broadly, the V4’s) ongoing struggle as the region increasingly relies on Chinese (and other East Asian) capital to transition from internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) to electric vehicles (EVs), which comes at a time when the EU is actively pursuing its strategic autonomy agenda. While such investments offer short-term benefits – advancing the V4’s and EU’s green and digital transition goals represented by the 2035 zero-emissions target – they bring a host of long-term (geo)political, (geo)economic and (cyber)security risks.

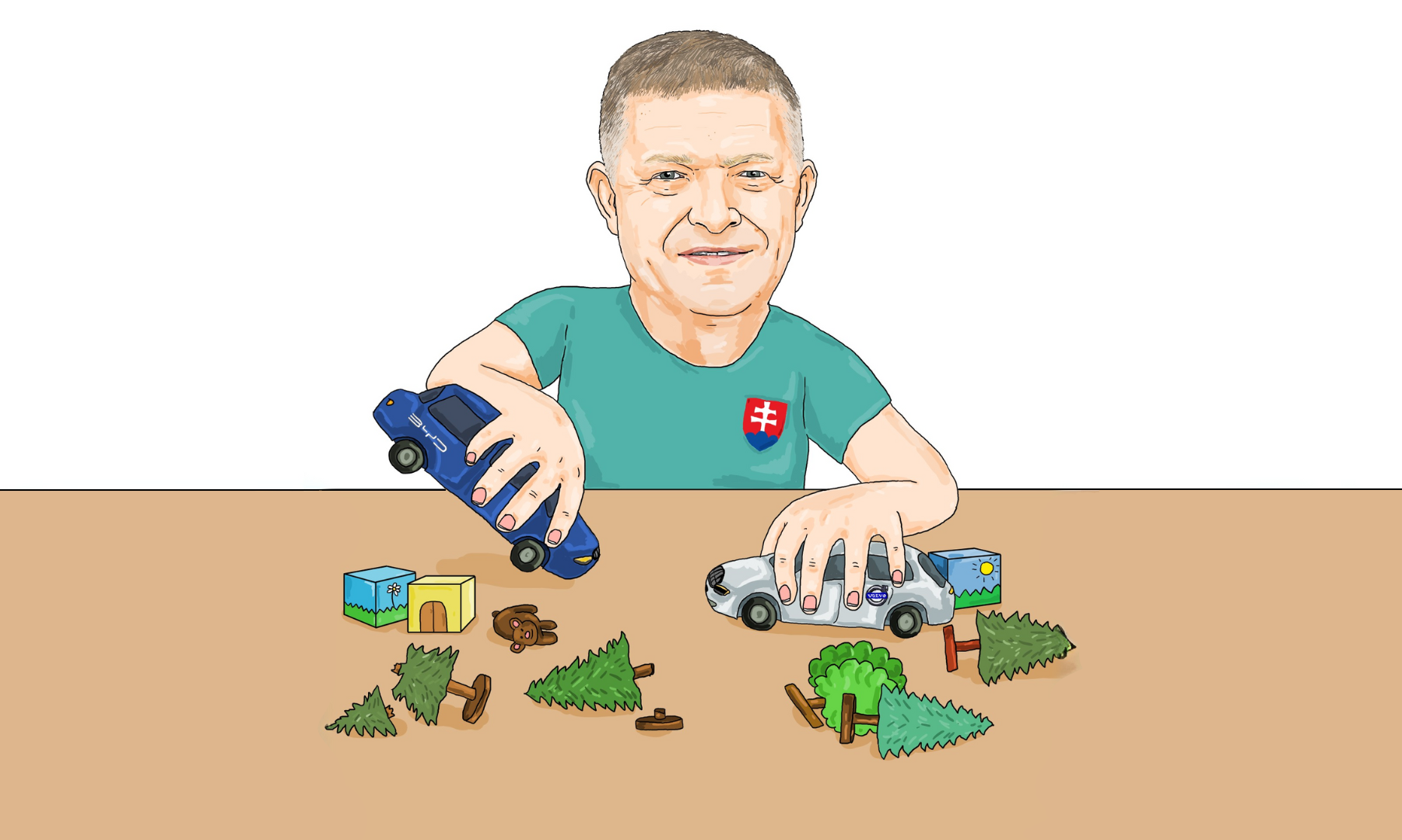

Moreover, the NIMBY sentiments underscore notable discrepancies between EU and Chinese regulatory standards. These could be further leveraged against both national and EU-wide interests, especially given the ongoing dilution of the EU’s Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) framework. At the same time, it is important to differentiate between various forms of these investments (including the nature and scope of activities involved) and their associated risks. This article explores these nuances by focusing on the €1.2 billion Chinese battery manufacturing plant in Šurany, comparing it with another €1.2 billion Chinese green tech investment in Slovakia – a Volvo EV manufacturing plant in Valaliky.

From Assembly Line to Battery Belt?

Slovakia’s automotive success story began in the 1990s, when Western automakers started outsourcing their manufacturing activities to the region, transforming it into what has been dubbed an “integrated periphery” of the European auto industry. This success, however, came with strings attached: the region became a manufacturing hub dependent on foreign capital, with high-value R&D functions retained in the home markets of the original equipment manufacturers and low-value assembly work delegated to the V4 suppliers.

Now, as the industry electrifies, Slovakia – nicknamed the “Detroit of Europe” – faces a new challenge. EVs require fewer components than traditional cars, threatening component manufacturing, which is a major sector of the broadly defined Slovak auto industry that employs over 250,000 people. More critically, batteries account for up to 40 percent of an EV’s value, making battery production (and recycling) the new centerpiece of automotive manufacturing.

Enter China. While Western automakers have been slow to adapt to the EV transition, Chinese companies have emerged as global leaders in battery technology and other key segments of the EV value chain. Across Central and Eastern Europe, Chinese investments are reshaping the automotive landscape, with Poland, Hungary, and increasingly Slovakia emerging as major battery hubs. However, most of these Chinese investments follow a familiar pattern of low-value assembly activities established by German automakers in previous decades. Slovakia stands out as the only country where a genuine “upgrading alliance” has emerged, centered around the Slovak battery start-up InoBat.

Two Towns, Different Reactions

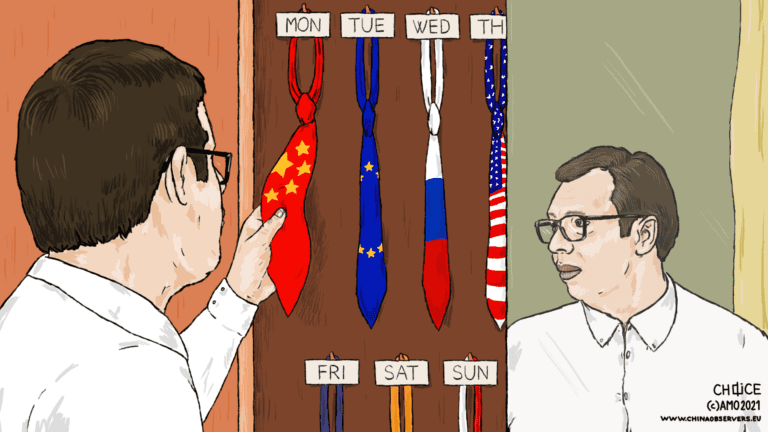

While InoBat’s joint venture with Chinese battery producer Gotion High-Tech is seen as a form of Chinese investment that could facilitate (some level of) industrial upgrading, it has also sparked local protests. The sustained opposition to Gotion InoBat Batteries (GIB) – particularly from the civil society group “Chránime si naše” (Protecting Ours) – contrasts starkly with the relative public acceptance of Volvo’s EV plant in Valaliky.

The difference is not just about brand recognition. While involvement of Chinese investors has been explicit in the case of GIB, few Slovaks realize that Volvo is owned by the Chinese manufacturer Geely. However, the extent to which this has affected local reception remains unclear. More importantly, battery manufacturing involves unfamiliar and potentially hazardous chemical processes, with the activists in Šurany citing concerns over substances like N-methylpyrrolidone solvents, which can affect fertility and cause vision, respiratory and other health problems, as well as worries about potential water contamination, soil erosion, high energy use, and pollution. All of this raises broader questions about environmental justice.

Šurany’s agricultural identity amplifies these concerns, with activists fearing the potential loss of farmland but also distortions in the local labor market, especially given the Nitra region’s low unemployment rates. This, according to the activists, directly undermines the economic arguments made by company and industry representatives as well as the Slovak government, which has declared the project a “significant investment,” exempting it from certain regulations. The lack of thorough public consultation and expedited approval processes forms another set of grievances.

In contrast, Slovakia’s long-standing success in automotive manufacturing and familiarity with this industry have fostered broader acceptance of the Volvo plant in Valaliky. The Košice region’s more diverse industrial landscape and higher unemployment rates may have also played a role in making residents more receptive to the Volvo investment, seeing it as an employment opportunity rather than a threat to existing economic activities. Importantly, the Valaliky Industrial Park was designated from the start for automotive manufacturing, avoiding ambiguities about its intended uses and providing a clear framework for transparent public consultation processes. These are some of the factors distinguishing the two Chinese investments at the domestic level.

The activists in Šurany have also drawn comparisons with other regional battery projects, notably CATL’s €7.3 billion plant in Debrecen, Hungary, which has attracted even larger opposition. These protests, however, were influenced not only by Chinese involvement but also by prior controversies surrounding South Korean battery investments, indicating broader concerns over lax ESG practices facilitated by a government that prioritizes economic development and profit maximization over local concerns and corporate sustainability – regardless of investor origin.

The ESG Clash

At the heart of these tensions lies a fundamental divergence between Chinese and European approaches to ESG standards. The EU has adopted some of the world’s most comprehensive sustainability frameworks, including the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities, the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). Amid rising concerns about the bloc’s competitiveness, recent proposals – such as those put forward in the “Omnibus package” – aim to simplify these frameworks, easing compliance by delaying reporting obligations, making them mandatory only for large companies, or limiting due diligence requirements to direct suppliers, thus significantly restricting value chain transparency.

While the EU faces criticism for aiming to weaken its ESG commitments, China has been advancing its own sustainability regulations, such as the Corporate Sustainability Disclosure Standards, which include Basic Standards, Thematic Standards and Application Guidance. These standards, however, remain voluntary for most companies until 2030, when full compliance under a unified national system is expected across a range of industries as well as small-and-medium-sized enterprises. They also lack enforcement mechanisms and reflect a different philosophical foundation, where sustainability is considered a component of national development that can be deprioritized if it constrains broader economic or security objectives. This creates practical challenges for Chinese firms operating in Europe and for EU regulators attempting to maintain consistent ESG enforcement, which is further complicated by notable discrepancies at the member state level.

Companies like Gotion High-Tech must demonstrate compliance with EU rules on mineral sourcing and manufacturing processes while remaining globally competitive, including against suppliers not subjected to such stringent requirements elsewhere in the world. The environmental dimension of ESG standards further demonstrates these divergent priorities. Despite their contribution to decarbonization, Chinese EV batteries often rely on critical raw materials sourced in environmentally and socially problematic ways in resource-rich regions of the Global South, posing further ESG concerns under European (albeit not necessarily Chinese) standards.

Strategic Autonomy or Dependency Trap?

Slovakia’s Chinese investments reflect a paradox. The GIB project is portrayed as aligned with the EU’s strategic autonomy agenda – both by the company and by researchers emphasizing the upgrading alliance that has emerged around InoBat (interpreted as the company’s strategic choice), suggesting potential for value creation beyond simple assembly. This stands in stark contrast to Hungary’s continued reliance on foreign capital (as outlined in its National Battery Industry Strategy 2030) which does little to change its value chain position or reduce dependency. This not only counters the EU’s pursuit of strategic autonomy, but also constraining the emergence of an upgrading alliance by effectively limiting the opportunity to induce value chain changes to structural and geopolitical shifts.

Yet, with Slovakia having the EU’s third-highest trade exposure to China and the highest final demand exposure among the V4, the country remains deeply exposed to potential Chinese economic coercion in both direct and indirect terms. On top of this, concerns about regulatory arbitrage – where investors exploit laxer national regulations – are rising, particularly around ESG enforcement (among other things), which, among other things, risks deepening intra-EU divisions. Indeed, Slovakia’s experience underscores the broader challenges facing EU member states as they try to balance economic development, the green transition, and national security. While Chinese EV investments promise the creation of thousands of jobs and other short-term benefits during this early period of industrial transformation, which is a key aspect the V4 elites must consider as the EV transition threatens traditional automotive employment (especially in component sectors dominating the region), their strategic implications cannot be ignored.

As Chinese investments grow in scale and strategic importance, the lack of a national ESG framework, weak regulatory mechanisms and tools for assessing FDI-related risks in greenfield projects and the automotive sector, which is not covered by the FDI Screening Act’s list of critical investments, become more pressing. Slovakia must therefore develop more sophisticated, cross-sectoral screening tools that can evaluate both brownfield and greenfield projects based on their specific characteristics and implications. The government should also ensure early, sustained community engagement to manage the social and environmental dimensions of foreign investment – especially from countries with different regulatory norms and business practices – with the adoption and implementation of a national ESG framework aligned with EU standards being another important step to consider.

As Slovakia pursues both economic growth and climate goals within the EU’s strategic framework, it must strike a careful balance: leveraging Chinese technology while upholding strong ESG standards. The resolution of these tensions will shape not only Slovakia’s economic future but also its position within the broader European and global strategic landscape.

Written by

Dominika Remžová

DominikaRemzovaDominika Remžová is a China Analyst at AMO, specializing in Chinese economy and industrial policy, supply chains, critical raw materials, electric vehicles and, more generally, Chinese foreign policy. In the past, she contributed to Taiwan Insight and The Diplomat, among others. Dominika is pursuing her PhD in Political Science and International Relations at the University of Nottingham. She earned her Master's degree in Taiwan Studies from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London and her Bachelor's degree in Chinese Studies from the University of Manchester.