Bucharest has abandoned the erstwhile drive to improve relations with China due to shifting geopolitical alignments and unmet economic expectations, with the bilateral ties now on auto-pilot.

A historic moment comparable to Romania’s entry into the EU and NATO. Those were the words that then-Prime Minister Victor Ponta used to describe the hosting of what was then the 16+1 summit in Bucharest in 2013.

Fast forward to 2023 and it becomes clear there was no “historic moment,” as the interest to engage with China disappeared without much trace. As Romania is the EU’s sixth largest member state, understanding what happened over the past decade can uncover broader shifts underway in China-EU relations.

Origins of the China Pivot

While Victor Ponta is generally seen as the most significant contemporary promoter of stronger relations between Romania and China, his predecessor, Emil Boc, also played the Chinese card. The Boc government approached Chinese companies for a possible investment in the Cernavodă nuclear power plant, which would later become a key Chinese project under Ponta. Romania was also an enthusiastic early participant in the China-CEE cooperation mechanism, with right-wing governments negotiating Romania’s hosting of the 2013 summit later organized by the left-wing Ponta government.

But it was Ponta who was the real driver behind improving relations with China, aiming to transform Romania into its “closer friend.” Personal affiliations and interests played an important role – Ponta visited China numerous times during his career and in 2006, he even got married in Beijing. After ascending to a leadership role in the government, he turned out to be maverick, frequently circumventing the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and engaging directly with Beijing. But the intensity of his personal involvement also meant that after his resignation following the tragedy of a deadly fire in a club in Bucharest in 2015, Romania’s relations with China have not been the same.

The numerous ‘revolving-door’ prime ministers who succeeded Ponta never engaged so much in promoting ties with China. On the contrary, some of them, like Sorin Grindeanu (2017) or Florin Cîțu (2021), were very reluctant to deal with Beijing.

Only Viorica Dăncilă (2018-2019), from the same left-wing party as Ponta, tried to pick up where Ponta left off in terms of the China policy. But her actions were in vain, as the political landscape (presidential elections in 2019 and the EU and the US recommendations) did not allow for the emergence of a new momentum for improving Romania-China relations. On the contrary, caught in the whirl of the presidential campaign, in 2019, Dăncilă signed an MoU with the US regarding civil nuclear power cooperation, which would later set the stage for the process of canceling the Chinese involvement in Cernavodă nuclear power plant, which she had tried to revive just months earlier.

Skeptical Shift

If 2013 marked a positive milestone in Romania-China relations, then 2019 brought about a significant shift in the opposite direction. Not only did Romania sign an MoU with the US regarding civil nuclear power cooperation, but also took the lead as the first country in the world to subscribe to an MoU designed to ban Huawei’s involvement in its 5G network, signaling a firm position in the emerging US-China conflict.

Thus, Romania showed that the initial enthusiasm regarding China was exaggerated and mostly due to the persona of Ponta. Bucharest understood that the project MoUs signed in 2013 with China were not so easy to negotiate or implement, and if it had had to choose between those project promises and the West, it would always opt for the latter, rather than waiting for Godot.

And Romania did prove to be a staunch ally. Not only did it ban Huawei from its 5G network and force telecom providers to remove the Chinese tech giant’s equipment from their existing networks in a few years, or cancel the Chinese involvement in the Cernavodă Nuclear Power Plant, but it also restricted Chinese companies from taking part in public tenders, especially in infrastructure, downgraded its participation in the China-CEE summit in 2021 to a ministerial level, and implemented a tough screening mechanism for non-EU investment.

At the parliamentary level, things went even further, such as a proposed bill intending to force public universities to close their Confucius Institutes by threatening to cut all their government funding, or closer engagement with Taiwan by some MPs.

Despite all these actions, at the government level, Romania has never engaged in direct criticism of China or its behavior, even when it came to the subject of human rights. At the same time, neither did China exercise any type of wolf warrior diplomacy in Romania. Interestingly, the deterioration of relations had no discernible effect on the Chinese ambassadors to Romania, who have a tendency of ascending to higher positions after leaving Bucharest, with the last three ambassadors promoted either to CEE envoys or assistant ministers of foreign affairs. Thus, Bucharest and Beijing successfully managed to avoid diplomatic conflict that has plagued the ties between China and Lithuania or the Czech Republic.

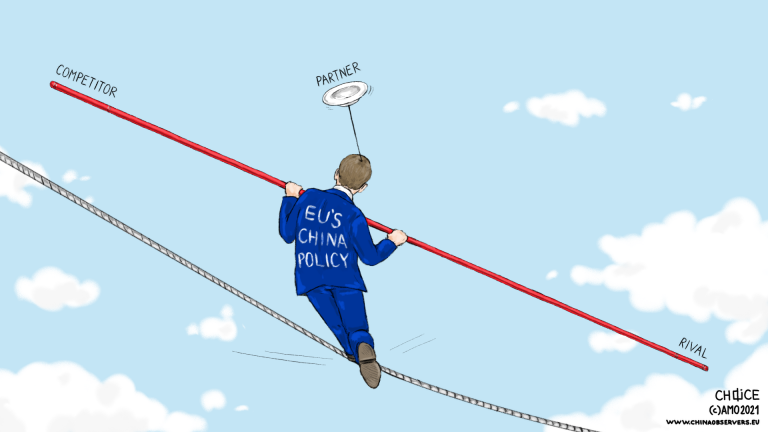

But while the Romanian government officially continues to claim that relations with China remain a priority, in fact, they are on auto-pilot. Over the past four years, Romania has not made any active steps to improve ties with China, with most government moves being restrictions. This approach is a consequence of both the larger geopolitical trend of blocks of power forming around the US and China, and Romania taking the US side, but also disappointment with China’s economic promises and the economic benefits of relations for Romania.

Most of this disappointment concerned projects proposed at the China-CEE summit in 2013, which was meant to start a new era of relations. According to an answer received by the author from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, over the years, Romania conducted an assessment of the format multiple times, concluding that it “did not see any concrete or substantial outcomes coming from this platform.” For Romania, the mechanism was supposed to be “a cooperation platform led only by an economic drive, which should not have political or ideological tones and should be used beside [the bilateral] Romania-China relations, which remain a priority for Bucharest.” Also, the ministry argued that the government prefers to prioritize engaging with China on a bilateral basis and on the EU level, instead of within the China-CEE format, as many fields included in the format pertain to EU competences. All these factors are highlighted by the recent nomination of the new Romanian ambassador to China, an economic official from outside the Foreign Ministry, who had extensive experience from his posting at the Romanian representation to the EU in Brussels, but lacks any experience regarding China.

To Leave or Not to Leave

Romania’s initial enthusiasm for China and the ex-16+1 format did not last long. In 2017, the Romanian prime minister skipped the Budapest summit without any concrete reason or explanation, while Bucharest hosted its first and only important sectorial cooperation forum within the format, the Ministerial Conference on Energy Cooperation, without much fanfare. Romania had been chosen to lead cooperation in the energy sector, a logical choice considering that several energy agreements worth almost $10 billion were signed at the 2013 Bucharest summit. While these agreements failed to materialize, Romania also displayed no interest in promoting energy cooperation within the China-CEE framework.

Romania’s skepticism regarding the China-CEE cooperation format was spurred by China’s lack of understanding of and involvement in the region. Ten years ago, China came to the CEE region as a dream-seller disguised as a keen investor. Many countries received only promises, instead of projects, thus leading to disappointment after some years. In Romania, China promised investment in numerous projects but also cooperation in areas like IT, green energy, infrastructure, or transportation. None of these projects came to life and the political mood towards China soured accordingly.

All in all, Romanian prime-ministers missed three China-CEE summits out of nine (2015, 2017, 2021), with the last absence being an intentional one, meant to send a signal. Today, there is a perception that Romania might be the next to leave the 14+1 format, but, according to a source familiar with the matter, for the moment, Romania does not intend to stop its participation altogether, but will further downgrade its activities. This trend has already started in 2021 when Romania sent its minister of economy instead of its prime minister or president to the 16+1 video-summit hosted by Xi Jinping. Not only was it perceived as a snub by all of Europe, but China also interpreted it as such.

In 2022, when China celebrated a decade of its cooperation mechanism with the CEE region in Beijing, Romania was not among the countries invited to the event. Curiously enough, according to the Romanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, such an event never happened at all. Romania has also not been very active at lower levels of cooperation within the China-CEE cooperation format. For example, Romania did not send any official delegation to the recent China-CEE Expo in Ningbo, while the Chinese side invited former prime-minister Viorica Dăncilă, who no longer plays any important political role after leaving the party she had led in government, which did not include her in its list of MP candidates.

While China still calls Romania an “old friend,” in reality, the relations between the two are cold and only live from the memories of the communist times and Ponta’s prime-ministership. Today, Romania is quite skeptical of engaging with China, mainly because of the geopolitical tensions between Beijing and the West and because, economically, China has failed to prove that it is a trustworthy partner. In this context, whether Romania stays in what is now the 14+1 mechanism or not does not matter much, as in practice it will continue to keep its distance from China while following the EU’s lead and remaining a firm US ally.

Written by

Andreea Brinza

AndreebrinAndreea Brînză is a Vice President of The Romanian Institute for the Study of the Asia-Pacific (RISAP). Her research focuses on the geopolitics and geoeconomics of China and especially on the Belt and Road Initiative.