Since autumn last year, many European countries have experienced a lack of medicines, ranging from children’s fever-reducing drugs to eye drops and antibiotics. Such shortages are caused by a number of factors, including fragile supply chains whose origins can often be traced to China.

Most of the world’s production of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), which represent the active and therefore key part of medicines (e.g., ibuprofen or paracetamol), are produced in India and China. Over the past two decades, production gradually shifted to Asia from Western countries due to lower production costs, including wages, and fewer regulatory burdens, especially environmental standards. The production of APIs involves processes such as fluorination and chlorination, which pose a potential risk of contamination of air, water and soil, and can generate hazardous waste during the production process.

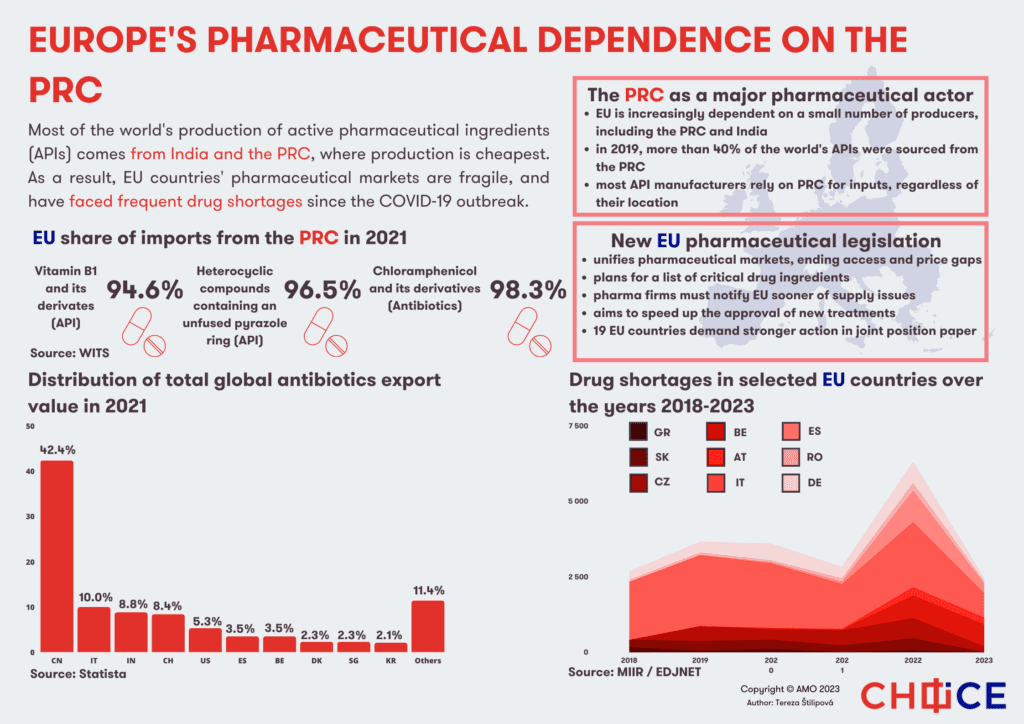

China currently produces about 40 percent of APIs, India about 20 percent, the US accounts for 28 percent, and Europe for about 26 percent, with the largest producers in Italy and Spain. Compared to their Asian counterparts, European manufacturers focus primarily on APIs that require complex manufacturing processes, higher quality or are used in low quantities. At least 93 different active substances, more than one-sixth of the substances analyzed in this study and used in Europe, are not produced by any manufacturer on the continent.

The growing influence of China and India in the production of APIs is also reflected in the granting of certification by the EU. While at the beginning of the century, the share of applications for certification by Chinese manufacturers was in the single digits percentage-wise, by 2020 China accounted for around one quarter of all applications. Indian applications make up an even larger share of the total with 40 percent, up from around 10 percent at the beginning of the century.

European Market Relies on Imports from China

The exact figures showing the dependence of EU countries on China for pharmaceuticals are difficult to quantify, but China’s dominance in the case of selected substances or vitamins is clear.

Data from 2021 show that approximately 95 percent of vitamin B1 and its derivatives imported into the EU came from China. Over 96 percent of the heterocyclic compounds with an unfused pyrazole ring, APIs used in many antibiotics, are also imported by the EU from China. An even higher dependency can be found for chloramphenicol and its derivatives, reaching over 98 percent. Chloramphenicol is a key substance for a wide-spectrum antibiotic used for severe infections that cannot be treated with other antibiotics.

Moreover, even when the active ingredients or the final drugs are manufactured in Western countries or in India, production often depends on imports of raw materials from China. For example, India imports about 70 percent of APIs from China, including those necessary for the production of antibiotics, paracetamol and drugs for diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. In fact, compared to India, China is able to produce APIs 20-30 percent cheaper, depending on the product, thanks to the availability of cheap raw materials. In addition to the production of the APIs, China is also a key supplier of excipients, meaning substances that improve, for example, the absorption, taste or physical properties of the drug.

Fragile Supply Chains

Centralizing the production of APIs in one country or region poses a major safety risk to global health. In addition, not only are the global supply chains sometimes largely dependent on one country, even within China, approximately 40 percent of APIs production registered by the US FDA is concentrated in the east coast provinces of Zhejiang, Jiangsu and Shandong. Thus, any problems in this part of China, from environmental disasters and power outages to political instability, can disrupt the production of key compounds.

For example, during the five-month pandemic lockdown in Shanghai, Indian companies feared disruptions in the supply of APIs and primary raw materials, as some of them are exported through the Shanghai port. Whereas there are no reports about these concerns materalizing, the pandemic served as a wake-up call and India has been trying to reduce its dependence on China, setting up a $1.3 billion fund in 2020 to produce more APIs locally.

In case of another pandemic or an international crisis, China and India may behave unpredictably or use their key position to their advantage. For example, India temporarily banned the export of paracetamol, antibiotics and other medicines and suspended exports of coronavirus vaccines for several months during the COVID-19 pandemic because of its own difficulties with the virus.

Meanwhile, China used the supply of both the personal protective equipment and vaccines for diplomatic purposes and to improve its image, which was tarnished after China faced criticism due to inadequate and delayed sharing of information at the onset of the pandemic. The availability of Chinese vaccines was thus determined by the bilateral relations – for example, in Latin America, all countries have purchased or received Chinese vaccines as a donation, except Paraguay, which maintains bilateral relations with Taiwan.

Importantly, Czech intelligence agencies emphasize pharmaceutical dependencies on China particularly in the context of a hypothetical conflict against Taiwan, as China could cut off the supply of medicines and APIs or use them to pressure European countries against supporting the island in the conflict.

Medicines as a Priority

China’s pharmaceutical market is currently the second largest after the US, and although most drugs produced in China are equivalent of those commonly available in the West, China is trying to move towards developing more sophisticated drugs, including biological pharmaceuticals.

With the aging population and increasing pressure on the health sector, the Chinese Communist Party needs to ensure sufficient supplies of medicines and address other health-related risks. Long-term plans define the development of new drugs and clinical medicine research as priority areas, specifically highlighting cancer treatment, cardiovascular and brain diseases.

In recent years, the Chinese government has introduced new legislation and synchronized its own regulations with international standards, including the drug testing process or the number of patients required for clinical trials. It also aims to encourage domestic companies to pursue innovations.

Inadequate Prevention of Shortages

The EU is currently preparing a new legislation to clarify and unify the pharmaceutical market and eliminate differences in availability and prices. Indeed, a number of factors are involved in the introduction of new medicines, ranging from the complicated process of drug authorization, pricing, cooperation with insurance companies and various constraints of the healthcare system. These circumstances then affect the decision of pharmaceutical companies regarding the countries which are offered the new medicine.

Besides unifying the market, the legislation also aims to prevent supply shortages. In particular, pharmaceutical companies will have to report about supply issues, planned interruptions or ending of production. Similarly, companies will have to assess the bottlenecks in their supply chains and develop plans to deal with potential disruptions.

The legislation will also include a list of critical medicines, shortages of which could lead to serious harm to patients. In their case, the European Commission will have the power to order the stockpiling of APIs or medicines.

However, the legislation avoids the issue of reducing dependence on China (and India) and does not mention the potential transfer of production to Europe. Consequently, the majority of member states are calling for stricter measures to strengthen the security of supply chains. A document reacting to the proposed legislation signed by 19 EU member states directly mentions dependence on China, and draws attention to serious security aspects – the concentration of production in a few areas and dependence on a small number of manufacturers.

Specifically, this document proposes a voluntary solidarity mechanism allowing the countries to request lacking medicines from other member states and a faster compilation of the critical medicines list. In the long term, the proposal foresees the creation of an act on critical medicines, which should be inspired by the Critical Raw Materials Act and Chips Act. This legislation should thus support the production of medicines, APIs and other substances, for which the EU is dependent on a small number of importers or a single country. As such, the efforts in this area are an important piece of the puzzle of the larger de-risking plans under the EU’s economic security strategy, which will require assessment and mitigation of risks across many different areas.

Written by

Veronika Blablová

Veronika Blablová is an analyst at CEIAS.