Despite more hawkish rhetoric from Warsaw, practical cooperation between Poland and China has remained surprisingly unaffected by the outbreak of the war.

Tensions between Poland and China had been on the rise well before the outbreak of war in Ukraine, mainly in the context of the Sino-American rivalry. This was illustrated by the arrest in January 2019 of a Huawei employee in Poland on charges of conducting espionage on behalf of China. Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has further exacerbated strategic issues directly related to the security of Poland’s national borders and put more spotlight on the role played by China.

Two Tracks

Before February 2022, a two-track approach of the Polish authorities towards China could be observed. Up until then, there was a division between the presidential office of Andrzej Duda – a strong proponent of Poland’s engagement with China – and the government of Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, which advocated for an assertive policy, or even containment of China.

However, the dichotomous division between ‘engagers’ and ‘containers’ is a generalization, as the two main strands occasionally intermingled, including on a personal level, as both centers of power originate from one political coalition led by the Law and Justice Party (PiS), which has led the government since 2015. For example, in September 2023, Jakub Kumoch, a close associate of President Duda and former head of the Presidential Office for international policy, was appointed Polish ambassador to China.

Significantly, less than three weeks before the outbreak of war in Ukraine, President Duda was the only EU country leader to attend the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympics in Beijing. The visit occurred despite the fact that many of Poland’s Western partners diplomatically boycotted the event due to human rights violations in China, especially regarding Beijing’s crackdown on the Uyghurs.

Before President Duda’s trip to Beijing, his foreign policy advisor, Jakub Kumoch, explained that it was Poland’s sovereign right to pursue “its own policy towards China,” arguing that “very friendly relations” do not conflict with Poland’s alliance with the United States. A year later, after he had already left the President’s Office, Kumoch explained that the visit to Beijing served to draw Xi Jinping’s attention to the fact that a Russian attack on Ukraine would be detrimental to China’s commercial interests and was a “dramatic attempt to bring about Chinese mediation in Ukrainian-Russian talks.” Although President Duda has become more restrained in expressing his cordial relationship with Xi Jinping against the backdrop of China’s continued support for Russia during the war, he has never publicly criticized China.

In contrast, Prime Minister Morawiecki has maintained a skeptical stance regarding Sino-Russian cooperation after the outbreak of war in Ukraine, expressing it publicly in Politico in June 2022. More to the point, given China’s support for Russia, a Chinese delegation led by Huo Yuzhen, the special envoy for the 16+1 (14+1) format, was not received in May 2022 by the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs during her visit to the region. However, despite its dissatisfaction with China’s stance, Poland assured Beijing that the country would remain in the China-led grouping, but would only selectively engage in its activities. Finally, in November of the same year, the Polish Foreign Ministry accepted Jiang Yu – Huo Yuzhen’s successor, when she visited Poland.

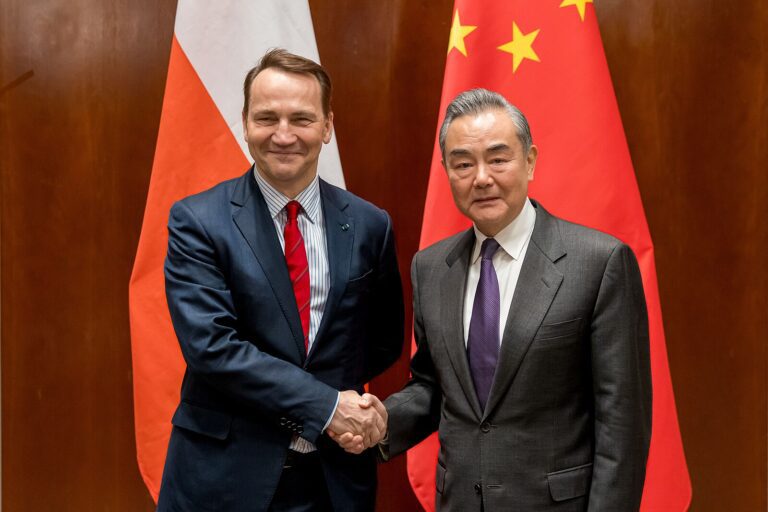

The war, and specifically China’s support for Russia, initially increased the narrative coherence of foreign policy pronouncements between the government (Foreign Ministry) and President Duda. In June 2022, Foreign Minister Zbigniew Rau spoke with his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi, indirectly drawing attention to Chinese support for Russia at the United Nations (UN) and appealing, albeit indirectly, for China to condemn Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. A month later, Andrzej Duda spoke with Xi Jinping, noting that Russian aggression was complicating trade relations between China and Central and Eastern Europe. The Polish president also pointed out that China could help restrain Russia’s attempts to trigger a global food crisis.

However, the Polish Prime Minister expressed much stronger views on China’s role in the war. Mateusz Morawiecki’s speech, delivered at the Atlantic Council in Washington in April 2023, drew sharp criticism from China’s Embassy in Poland. Having assessed that the collapse of Ukraine would prompt China’s invasion of Taiwan, the prime minister expressed the hope that China would not cross a red line by supplying arms to Russia.

The growing impatience with China’s stance on Ukraine is reflected in the position of the Polish Foreign Ministry, following a conversation between Deputy Minister Wojciech Gerwel and the Chinese government’s special envoy, Li Hui, in May 2023. While describing Beijing’s (long-delayed) initiation of dialogue with Kyiv as positive, the Polish government made it clear that China’s equating victim with aggressor was unacceptable. Furthermore, Poland expressed its firm support for Ukraine’s peace proposals. It called on China – a member of the UN Security Council and the chief advocate of the five principles of peaceful coexistence – to condemn Russian aggression and restrain Moscow’s actions.

While the position put forward by the Foreign Ministry at the time was very pertinent, articulating not only Beijing’s disregard for the legal and international situation in the face of war but also China’s selective adherence to its own foreign policy norms, it was expressed on a relatively low bureaucratic level, which limited a potential backlash from China.

One would, therefore, expect that China’s political, economic, and perhaps also military support for Russia, which has been criticized to a varying degree by the Polish authorities, would curtail the scope of cooperation between Warsaw and Beijing, especially in those areas that may be an issue for Polish national security. However, regarding practical cooperation on the ground, the war has essentially changed nothing.

Business as Usual

Despite the spying controversy, Huawei’s involvement in the Polish 5G network still remains a realistic scenario. In September 2023, the Morawiecki government once again withdrew an amendment to the law on the National Cyber Security System, without which a 5G auction cannot be held. Work on this legal document has already dragged on for three years. It is still unclear which companies will finally be included in the list of high-risk providers and in turn, whether any Chinese vendors will be allowed to compete in the Polish 5G market.

Even though Huawei has been described in the past, both by Prime Minister Morawiecki and the Head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration, Mariusz Kamiński, as an almost existential threat to national security, the Polish authorities are stalling the introduction of legislation that would restrict the scope of the Chinese telecommunication giant’s operations in Poland. The potential restrictions on TikTok’s use on government devices seem to be locked in a similar stalemate. Although the government’s action against the Chinese app has been talked about since 2020, a decision has still not been taken.

The Huawei case embodies the nature of Polish foreign policy towards China. In rhetorical terms, Warsaw’s approach is very much characterized by traditional anti-communism and declarations about the need to defend Poland and the ‘free world’ from the threat posed by China, as expressed by both Prime Minister Morawiecki and the heads of the Polish defense and internal security ministries. However, this criticism is usually voiced in media outlets or expert forums rather than through official channels. In contrast, at the official level, growing impatience with China’s stance on Ukraine is communicated mostly through lower bureaucratic channels. Furthermore, despite the overall sentiment for caution, there is a considerable number of “engagers” within the government, mainly linked to the agro-food, railway, and mining sectors, who are vying for a friendly attitude from the Chinese administration.

Poland also remains a member of China’s 14+1 format, although this has not translated into any economic benefits for Poland and has provided China with reasons to show, at least in Beijing’s eyes, that the country and 14+1 can to some extent serve as a counterbalance to the EU. Still, it should be noted that even the Czech authorities, which have been openly distancing themselves from the 14+1, have so far not decided to leave the Chinese initiative. Naturally, the motivations behind Warsaw and Prague’s persistence in the format are not necessarily the same, with the former seemingly using 14+1 to counterbalance its relations with the EU, especially with regard to Poland’s conflict with Brussels over legal issues.

Poland’s interest in the opportunities offered by the Chinese financial market, which intensified during the dispute with the European Commission over the disbursement of significant funds from the National Reconstruction Plan, seems to follow this logic as well. Both the issuance of yuan-denominated Polish bonds on the Chinese market (c. $450 million) and the loans from Chinese banks taken out in February and – already after the outbreak of war in Ukraine – August 2022 by the state-owned gas company PGNiG (a total of approx. PLN 1.77 billion), happened at a time when Warsaw was still waiting for major European funds to be unfrozen.

In turn, at the bilateral level of cooperation with China, Poland is struggling with a huge trade deficit. Between January and May 2023, Poland’s exports to China amounted to PLN 4.6 billion, while imports from China totaled PLN 72.2 billion. In addition to the limited potential of the Polish economy, this imbalance is exacerbated by the regulatory barriers with which Beijing impedes the expansion of Polish entrepreneurs in the Chinese market, and by Poland’s position in the global supply chains (as a sub-supplier to German exporters).

Nevertheless, the Polish side provides China with a stable and open business environment. This is illustrated by many road and rail infrastructure contracts awarded to large Chinese state-owned companies. This includes a consortium of Poland’s Intercor and China’s Stecol, which in August 2023 won a significant contract for extending the main railway line through Katowice. Interestingly, Polish State Railways (PKP PLK) assumed a budget of $920 million for the project. However, during the electronic auction, the Intercor and Stecol consortium almost halved its initial offer to $880 million, which probably would not have been possible without the support of Chinese state funds for the latter company.

Envisioning EV Future with China

Plans for extensive cooperation with a Chinese partner were also signaled by Piotr Zaremba, CEO of ElectroMobility Poland – a company that was established to create the first Polish electric car, the Izera, and in which the Polish State Treasury is the majority shareholder. Although it soon became apparent that the Izera would be a Chinese car under the guise of a Polish brand (based on the platform of a vehicle produced by the Chinese carmaker Geely), Zaremba suggested the Izera factory could also be used as an assembly plant for Chinese car prototypes. At the same time, Zaremba rejected criticism for cooperating with Geely, which is included on the Ukrainian list of sponsors of the Russian war, pointing out that “today all the major players cooperate with China.” Indeed, this rationale can be applied to the business-oriented approach demonstrated vis-à-vis China during the war in Ukraine by the leaders of Germany and France.

At the same time, the production of Geely cars in the Izera factory might, in practice, open up the European market for the Chinese company. It is all the more important because the European Commission has launched investigations into subsidies for Chinese and other electric car manufacturers in order to stem the flow of cheap electric cars. If Chinese cars continue to flood the European market, there is a risk that the EU’s green transition, rather than being a boost for the European car industry, could be a final nail in the coffin for the sector.

In its dispute with the European Commission, China will likely find an ally in Hungary, where factories of Chinese electric vehicle battery manufacturers (CATL, EVE, and Sunwoda) will be located to primarily meet the demand of the German car industry. Hungary is also a home for China’s BYD first electric bus factory in Europe, though the company’s first European subsidiary was established in the Netherlands.

On August 27, just a few days after the EU announced an investigation into Chinese EVs, Foreign Minister Wang Yi told his Hungarian counterpart, Peter Péter Szijjártó, that China expects Hungary to “push the EU to adopt a more open policy towards China.” In turn, Szijjártó not only asserted that Hungary was firmly against “decoupling” from China with any EU action incompatible with the principle of “fair competition,” but also thanked Beijing “for its active efforts to achieve peace in Europe.” This situation shows how China’s economic involvement may translate into political influence, or as in the case of Hungary, underpin its political clout.

Stable Cooperation or a Wider Opening?

As of Autumn 2023, Poland’s relations with China seemed to be back on a pre-war track, at least as evidenced by economic interactions. The recent developments seem to confirm that despite the economic and political support given to Russia, China remains an important economic partner for Poland. The appointment of Jakub Kumoch, a close associate of President Duda who has been an advocate of engaging with China for years, as Polish ambassador to China, seems to support the fact that China remains economically significant for Poland.

For now, however, it is difficult to assess whether the recent developments herald a deeper thaw in Polish-Chinese relations and to what extent the activity of Chinese economic entities in Poland will translate into improved bilateral relations and bring an increase in China’s political leverage.

Finally, the future trajectory of Poland’s relations with China also depends on the results of the upcoming elections. A new government might be more prone to align the assertive rhetoric with a significantly more ‘hawkish’ position towards economic and political cooperation with Beijing. At the same time, impending troubles of the Polish economy might just as well push Warsaw to tap deeper into the opportunities (real or imagined) offered by Beijing.

Written by

Bartosz Kowalski

BartekKowalski1Bartosz Kowalski is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Asian Studies of the University of Łódź, Poland, and a Researcher at its Center for Asian Affairs. His research focuses on China’s foreign policy, including relations between China and Central and Eastern Europe.