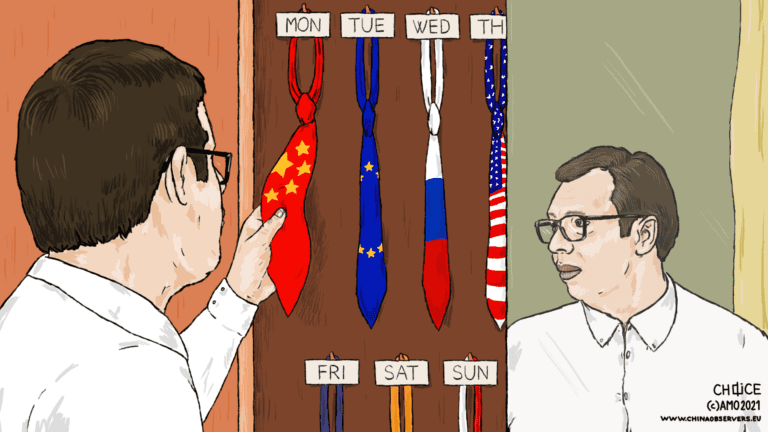

For years, concerns in Brussels and Western European capitals about the security of southeastern Europe have centered on the threat posed by Putin’s Russia. But behind these fears the question of China looms large.

Russia’s efforts to expand its influence in the Balkans have caused concern among analysts and politicians in the West in recent years, and worries Russia might double-down on efforts to destabilize the region have lately deepened with a French veto of EU membership talks for North Macedonia and Albania.

But while concerns about Russia remain crucial, they should not distract from what is now the central challenge for the EU’s dominance in the Balkans: China.

Russia has largely been a spoiler power in the Balkans, with some leverage on issues such as Kosovo dispute and energy politics. Its policies, however, have been unsuccessful, as showcased by Montenegro’s membership in NATO and resolution of Macedonia’s name deal, both of which Moscow opposed.

China, on the other hand, is a newcomer whose economic clout and promised financing through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), as well as other forms of engagement, present a real challenge in terms of short and medium-term alternatives, potentially diminishing the appeal of the EU model.

Reality Checks

When assessing the relative challenges posed by Russia and China, we need first to have a clearer view of Russia’s strategic capabilities. In fact, Moscow is neither capable nor interested in offering an alternative to the EU and Western institutions, and this fact conditions the Russian approach to the Balkans. Instead, Russia tries to obstruct Western players in the region, but even in this objective, Moscow has proven largely ineffective, as evidenced by two major policy failures – Montenegro’s successful NATO membership in 2017, and the pending addition of North Macedonia to the security alliance, which should be formalized in December.

A strong case can be made that Russia is overestimated within the European policy community as a strategic force in the Balkans. One example cited in support of the idea of Russia at a strategic power in the region is the failed coup attempt in Montenegro back in 2016, which some have interpreted as an example of Russian hybrid warfare. Others have questioned Kremlin involvement, citing a history of such affairs in Montenegro.

Earlier this year, several opposition politicians and alleged Russian agents were sentenced to jail terms for their involvement in the coup attempt, but it is still not at all clear that Moscow played a primary role[DB1] . Maxim Samorukov, an expert at the Carnegie Moscow Center, has noted a number of inconsistencies in the indictment against the alleged conspirators, adding that if there was a Russian involvement in the country its intent was to organize anti-government protests, not to stage full-scale coup. American journalist Valerie Hopkins has similarly highlighted problems and inconsistencies in the “murky tale” surrounding the alleged coup attempt.

Despite these lingering questions, the case has fuelled the sense that Russia is a rising strategic menace in the region, and perhaps the key threat to EU interests. However, regardless of all the conflicting interpretations of the Montenegro coup, one thing is for certain. The fact that Montenegro did join NATO in the end, shows limits of Russian power despite the sense that Russia has its finger in every crisis in the region.

During the political controversy surrounding resolution of North Macedonia’s long-standing dispute with Greece over its name, which was key to paving the way for North Macedonia’s closer alignment with the West (including its NATO membership), Russia was again portrayed as a primary threat.

The view of Russian interference was of course not essentially wrong. An aggressive disinformation campaign on social media was documented, including the proliferation of pro-Russian content during the referendum on the Macedonian name deal, leading to understandable speculation of Russian involvement. In August 2018, Greece expelled Russian diplomats, who faced accusations that they had communicated with opponents of the deal in Greece in an attempt to sabotage the agreement with Macedonia.

But despite this disruptive nature of these activities, the Russian approach to North Macedonia is perhaps better understood as a reaction to local opportunities, as opposed to a long-term strategy or geopolitical plan. The exact level of Russian involvement in Montenegrin and North Macedonian dramas can be debated, but one conclusion is certain: Montenegro’s NATO membership and North Macedonia’s pending NATO membership and closer engagement with the EU constitute a failure of Moscow’s policy in the region.

The Balkans and Southeast Europe remain outside the reach of Russian military power capabilities. Most of the countries in the region are already NATO members, and those that are not, including Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, are physically encircled by NATO countries. The sole exceptions are Bulgaria and Romania, which are, as Black Sea littoral countries, affected by growing Russian military capabilities in the Black Sea.

Russian power in the Balkans is also constrained by economic limitations given the stagnating state of the Russian economy. Russia’s economy, which was smaller in GDP terms in 2018 than that of the US state of Texas, logged a growth rate of just 0.9 percent in the second quarter of 2019. A 2018 report by the Center for the Study of Democracy, a Bulgarian think tank, showed that Russian foreign direct investment (FDI) stock as a share of GDP among Balkan countries was negligible, with the exception of Montenegro. Figures for Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia were below five percent.

This leaves energy as the only domain of economic power where Russia has a genuine strategic footprint in the Balkans, given the regional dependency on Russian gas supply. This does not, however, make the region unique compared to the rest of Europe. Finally, while the Kosovo dispute remains a cornerstone of Russian influence in Serbia, a country central to the Balkans region, and has an impact on wider regional diplomacy, this point of pressure can be expected to disappear once Serbs and Kosovo Albanians have reached an agreement.

In a Different League

This is where the story of Russian influence ends and the story of Chinese influence starts. Chinese interactions with the Balkan region have historically been limited in terms of real geopolitical and economic substance. However, the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), introduced in 2013, has enabled China to become a more conspicuous and assertive player in the region.

The BRI and its broader vision of connectivity and economic and political engagement potentially puts China in a position very different from that of Russia in the Balkans. As I said previously, Russia has not been able to offer an alternative geopolitical vision to the Balkans, and has limited its activities to disruption of the strategic visions of the EU and the West.

The same cannot be said for China. Under the leadership of Xi Jinping, China has presented its own integral vision of the international system – a vision of the Eurasian continent unified under China’s strategic, political, infrastructural and economic patronage. These promises have come with the concerted re-branding of China as a benign, rising global power that is returning itself and the world to past glories. The message to smaller nations, like those in the Balkans, is that they can have a piece of the action if they sign up to this vision, accepting its premises.

Under this vision of the new global order, the Balkans is told that it has a special place, thanks to its geographical location where Europe meets wider Eurasia and extends into the Middle East and North Africa. For the countries of the Balkans, this vision potentially has more appeal than being abandoned to the European periphery, an anxiety that seems a present reality in light of the deadlock in the EU over the enlargement process.

China does not necessarily seek to derail the Balkans’ path towards integration with the EU, considering that increased connectivity with Europe is one of the core elements of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Nevertheless, Beijing’s growing involvement in the Balkans is potentially worrying news for Europe in light of the strategic disorientation of the EU, and against the backdrop of the uncertain state of European relations with the United States. The danger is the Europe might become, without strong leadership and consensus, what Henry Kissinger called a mere “appendage of Eurasia,” dominated by China and its economic and broader strategic vision.

The fact that China, quite unlike Russia, has both a strategic vision and the economic weight and willingness to invest in the Balkans region is a serious challenge that complicates Europe’s position.

As Bulgarian political scientist Dimitar Bechev, one of the most astute observers of affairs in the Balkans, has noted: “While Russia is good at playing the Slavic brotherhood card and loves to talk tough against the West, it lacks the economic heft to present a credible challenge. China, with a GDP of more than $12 trillion, is in a different league.”

Big Ambitions

China’s economic presence can be felt right across the Balkans. This reality is most pronounced in Serbia, geopolitically the most important country in the region. The country’s minister of infrastructure, Zorana Mihajlović, publicly flaunted the fact earlier this year that Serbia received 5.62 billion US dollars in Chinese investment financing and loans. “Ongoing Chinese (infrastructure) investments,” she told the Reuters news agency, “are almost 5 billion euros.”

China’s outreach has of course extended to other countries. A centrepiece of its strategy in the region has been its purchase of the port of Piraeus on the coast of Greece, which China has envisioned as a key gateway into the Western Balkans. Further up the Adriatic coast in Montenegro, China has provided a loan for the construction of a highway connecting the port city of Bar with the Serbian capital of Belgrade. The project, which bears a total cost of 1.3 billion Euro, has gone ahead despite two feasibility studies concluding that it is economically unviable. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, China has provided a loan to finance the construction of a thermal power plant in the city of Tuzla. While Bosnian officials have argued that Chinese upgrades at Tuzla will reduce pollution levels in one of the most polluted areas of Europe, critics argue that Chinese involvement has committed Bosnia to decades of coal consumption even as the EU is moving in the opposite direction.

The European Union remains the primary economic partner in the Balkans. What makes Chinese investment and engagement different, however, is China’s strategic focus on critical sectors of national infrastructure, as evident from the projects cited above – just a glimpse of China’s larger ambitions. China’s infrastructure financing is premised on the urgent need in the Balkans for improvement of core infrastructure, and China is capitalizing on the fact that the EU funds such as the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA) can be difficult to access either owing to enlargement deadlocks or to bureaucratic procedures and concerns about transparency standards.

For the local political elites in the Balkans, the Chinese offer can be too tempting to refuse. The non-transparent projects and contracts implemented by the Chinese in the Balkans under the auspices of BRI are for many local elites far preferable to the cumbersome compliance demands of the EU. China has also recognized how attractive the promise of swift financing can be in light of local political cycles, with infrastructure loans or investments from China offering politicians in the Balkans opportunities for self-promotion ahead of elections.

Chinese leaders have stressed that Beijing does not seek to export its development model, but BRI, even without offering systematic innovation, is a strategic alternative with implications for the EU’s open and transparent model.

The EU’s ability to set standards in the Balkans has already been impacted by Chinese financing. The highway project in Montenegro, for example, was initially rejected by the EU and international institutions including the IMF on the grounds that the project inflated the country’s national debt. The new Chinese financed coal-fired power plant in Bosnia and Herzegovina was criticized by EU officials on the account of its environmental impact. But China, which seeks strategic footholds in the region, has no such compunctions about debt implications, project viability or social and environmental impact. This has diminished the leverage the EU has with countries in the Balkans, which now see a Chinese alternative.

China’s direct leverage over the region has also become a question of some urgency. A report from the Munich Security Conference this year raised concerns about the implications of increased reliance on Chinese loans. “While Beijing supports EU accession of the region, its activities have raised suspicion within the European Union that China may exploit its economic heft for political gains,” the report said. “In addition, Chinese projects do not necessarily conform to EU standards of sustainability or transparency. China’s economic outreach thus poses risks to the region, notably in terms of debt, because much of the investment comes in the form of loans.”

China’s direct leverage over the region has also become a question of some urgency. A report from the Munich Security Conference this year raised concerns about the implications of increased reliance on Chinese loans. “While Beijing supports EU accession of the region, its activities have raised suspicion within the European Union that China may exploit its economic heft for political gains,” the report said. “In addition, Chinese projects do not necessarily conform to EU standards of sustainability or transparency. China’s economic outreach thus poses risks to the region, notably in terms of debt, because much of the investment comes in the form of loans.”

A European Commission communication in May this year called EU enlargement a “geostrategic investment in peace, stability, security and economic growth “ for all of Europe, and noted the risks posed by China’s unique form of engagement in the region. “China’s business and investment activity in the Western Balkans has been on the rise and can in principle offer opportunities for the region,” it said. “[H]owever, these investments very frequently neglect socio-economic and financial sustainability and EU rules on public procurement, and may result in high levels of indebtedness and transfer of control over strategic assets and resources.”

Certainly, some EU officials have recently spoken up about the changing geopolitical realities in the Balkans. In March 2019, Johannes Hahn, the now outgoing EU official in charge of enlargement, remarked: “Maybe we have overestimated Russia and underestimated China.” With the formation of a new European Commission, there is now talk of a “Geopolitical Commission,” with a much greater focus on ensuring that “external action becomes more strategic and coherent.”

This could mean a shift in the EU’s approach to the Balkans. But this would require action, not just rhetoric. The EU needs to invest time and resources, on the one hand, in a more concerted information campaign to win the hearts and minds of citizens in the Balkans. Beyond this, it will need to mobilize funding for key infrastructure more effectively, with fewer administrative and legal delays, demonstrating to Balkan countries that the EU is committed to the region’s development.

Most important of all is the accession process for the region. It is still true that in the long term, EU membership remains the best hope for the Balkans. But politicians and citizens in the Balkans can hardly be expected to sit on their hands, awaiting an end to the political and bureaucratic deadlocks in Brussels and European capitals – not, at least, while Chinese promises dangle so closely within reach.

This article has been originally published at Echowall and is republished here with permission with slight changes.

Written by

Vuk Vuksanovic

v_vuksanovicVuk Vuksanovic is a PhD Researcher in international relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), an Associate of LSE IDEAS, LSE’s foreign policy think tank, and a Researcher at the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy (BCSP).