Comparative Analysis of the Approach Towards China: V4 and One Belt One Road

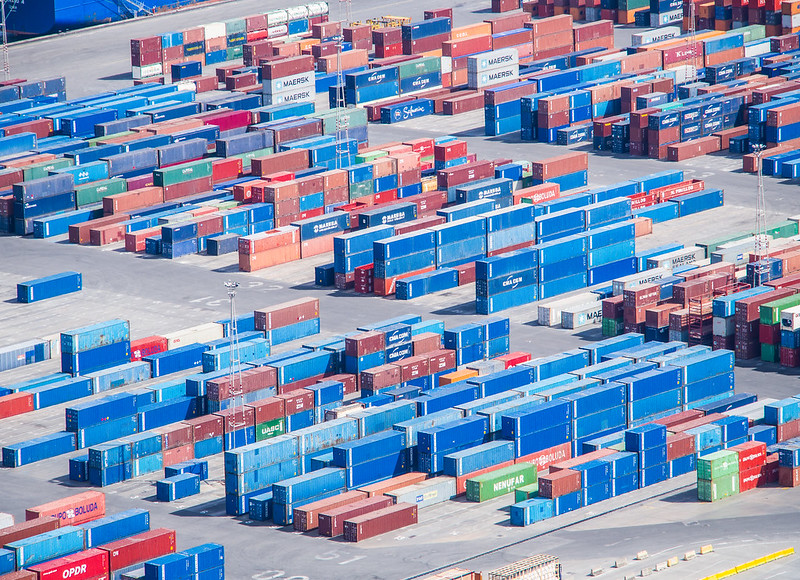

China’s emergence over the last two decades as one of the world’s major economies has had a transformative impact on international economic relations. Its rise as a global economic power has shifted the geographical concentration of financial capital eastward and forced firms across nearly all countries and spheres of production to compete with Chinese exporters, with often significant effects on their national economies. In 2013 China announced its “Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)”, a global infrastructure project intended to link markets around the world together in a China-centric trading network, comprised of overland and sea transport routes. Practically speaking, the core strategy of the project appears to be improving market access for Chinese exporters, as well as expanding China’s influence in the countries involved. But at a symbolic level the project has become a bid for rivalling the US-EU-centered global economic order. The countries of Central Europe are expected to play an important role in the European element of the BRI strategy, given both their own expanding consumer purchasing power and the fact that they hold the key to overland routes connecting China to its largest export markets in Europe, including Germany, France, and the Netherlands. Central Europe might be perceived as a relatively underdeveloped region eager to attract new sources of growth, as well as one composed of small states with little claim to bargaining power in the face of an economic behemoth like China. This narrative would predict few obstacles to China becoming a dominant actor in the region.

The aim of this volume is to show that it is not all so simple as that. This comparative analysis of economic relations between China and the Visegrád countries + Serbia reveals that while China’s role in each of their economies has grown over the last decade, developments have been anything but homogenous, and that concerns about China’s impact on national security will be a critical factor in the success of the project. Using a common analytical framework across each of the chapters, these countries’ relations with China are reviewed in terms of recent bilateral trade and financial data, major investment projects, and the impact of national investment screening activity. A complex overview of bilateral dynamics emerges out of this framework. The variety of results suggests that no matter the disparity between China and its partners in economic power or the financial incentives it may be able to offer, realizing the BRI is dependent on the quality of China’s relations with each of the individual sovereign nations involved. Taken together, the results of this volume suggest that China cannot take anything for granted.

Ágnes Szunomár of the HAS Centre for Economic and Regional Studies and Tamás Peragovics of the Institute of Economics begin our volume with their insightful chapter on Hungary’s relations with China. Hungary has arguably emerged as China’s most enthusiastic partner among the Visegrád countries, but the authors point out that much of the relationship continues to hinge on decisions made by a handful of key corporations and thus the future remains difficult to predict.

Bruno Surdel of the Centre for International Relations (CIR) in Warsaw show the importance of modest expectations in his thorough review of Polish-Chinese relations. Initially treated with great fanfare by both governments, Poland’s presumptive role as China’s key Central European partner has largely failed to materialize. Disillusionment with the gains achieved so far has left Poland without a clear vision for its future dealings with China.

Bringing important perspective on BRI activity in a country in the Central and Eastern Europe region but outside of the EU, Stefan Vladislavjev of the Belgrade Fund for Political Excellence (BFPE) provides the details of Serbia’s rapidly-evolving partnership with China. The recent rollout of high-profile investment and infrastructure projects has endeared China to the Serbian government and the public, but whether the substantial debt Serbia has incurred along the way will justify itself is yet to be seen.

The Institute for Asian Studies (IAS) gives us Matej Šimalčík’s convincingly-argued chapter on Slovakia’s cautious relations with China, which are tempered by both Bratislava’s focus on continued integration with Western Europe and by its security concerns surrounding increased ties to China. This chapter’s review of the significance of investment screening in this context is particularly instructive.

Finally, Jakub Tomášek of the Prague Security Studies Institute (PSSI) examines the state of Czech-Chinese economic relations. In-depth case studies of several Chinese firms’ experiences illustrate the obstacles they face despite the Czech government’s apparent support for deepening ties. The chapter emphasizes the importance of the distinction between official rhetoric and actual economic outcomes, as well as the role of negative Czech public sentiment towards Chinese business in limiting China’s potential role.

Text was edited by Zack Kramer.

Conclusion

The character of each of the Visegrad countries + Serbia countries’ economic relations with China are fairly similar. Each recognizes China as a potentially important partner due to the size of its economy and expanding FDI portfolio, but faces security concerns about granting a foreign power too much influence in its domestic affairs and skepticism about China’s long-term intentions. In addition, none of these countries are willing to alienate their European partners in pursuing deeper relations with China, as the other EU countries in general and Germany in particular remain primary economic partners for all of them. Each country is forced to strike a balance between creating favorable conditions for China to drive economic growth and preserving an independent voice in negotiations and overall national security.

It is in their particular approach to this balance that most of the variation in these countries’ relations with China is found. To summarize this volume’s findings, Hungary was the first in the region to sign on to the Belt and Road Initiative and since then has taken a relatively welcoming approach to Chinese activity in the country. Poland expressed initial interest in working with China, but has been disappointed by the persistence of limits on its access to the Chinese market and lower-than-expected investment levels. Serbia looks set to play a critical role in the BRI infrastructure and has high hopes for its partnership with China. Slovakia’s relationship with China remains limited and characterized by concerns about Chinese respect for Slovak sovereignty and security. And finally, the Czech Republic’s politicians showed strong interest in a greater role for China in the country’s economy, but for a variety of reasons it has so far mostly failed to materialize.

It would be a great oversimplification to say that the variation in these countries’ approaches to relations with China could be explained by a single variable. But it is worth noting that there does seem to be a strong negative correlation between recent national GDP growth and the extent to which strong economic ties between these countries and China have materialized. According to the World Bank, between 2010 and 2017 Hungary averaged GDP growth of 2.1%, while in Serbia growth over the same period averaged just under 1%. Compare this with Poland (3.5%) and Slovakia (3.1%), and it seems that a country’s willingness to agree to the terms on which China wants to do business may largely be a function of the health of its underlying economy. In other words, countries with relatively weak prospects for growth may be those most willing to yield to Chinese terms. The Czech Republic grew 2.2% per year over this period, but with the highest level of GDP per capita in the region it may also be considered a relatively strong economy.

While it may seem obvious that those countries lacking other prospects for growth would be those most interested in opening up to Chinese interests, this nonetheless has important implications for our understanding of China’s role in the region. Overall, it suggests China’s influence may remain concentrated in Europe’s more peripheral economies, rather than the more robust markets in which China holds the strongest long-term interest. But perhaps more importantly, it suggests that, given a fairly high degree of economic security, the countries of Central Europe and possibly elsewhere may prefer not to have much to do with China after all in order to preserve their national autonomy and security. Judging by the casestudies in this volume, investment from China on Chinese terms appears to be more of a last resort than a truly appealing prospect. Ultimately, this illustrates the importance of continuing Central and Eastern Europe’s integration with the Western European economic core of the EU, a process that may be aided by the emergence of a cooperative framework for investment screening mechanisms. And finally, it shows us that there is nothing “set in stone” about the form the BRI project will take in this region; the grand transnational logic of reviving the ancient “Silk Road” will inevitably have to be reconciled with the present-day reality of a world of legally equal sovereign states representing their own diverse interests.

The summary is published based on permission from the Prague Security Studies Institute (PSSI). The study in full can be downloaded here (pdf).

Written by

Prague Security Studies Institute (PSSI)

PSSI is a non-profit, non-governmental organization established in early 2002 to advance the building of a just, secure, democratic, free market society in the Czech Republic and other post-communist states. http://www.pssi.cz/