China’s Narrative Warfare in Africa: Influence and Mechanisms

This article is based on a research report titled ‘Strings attached: China’s narrative influence in Sub-Saharan Africa’ originally published on January 30, 2025, by Hybrid CoE.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is frustrated that its economic and military power has not translated into significant political influence on the international stage, which it attributes to the West’s narrative hegemony and its impact on global governance, values, and norms. As a result, China acknowledges the strategic importance of narratives in shaping global perceptions and enhancing its image, as encapsulated in the concepts of “narrative warfare” and “narrative power,” the latter referring to the ability to shape the global order to one’s advantage by promoting an alternative vision of this very order.

Unable to confront the West directly, China has sought to erode its narrative hegemony by gaining influence in the Global South. The CCP deploys narratives to manipulate the information environment in support of its broader agenda – a strategy elevated to a top priority in Xi Jinping’s 2013 speech on national image building. These narratives frame global events as a rivalry between traditional and emerging powers, the former portrayed as colonial actors that have harmed and continue to exploit the Global South, and the latter, including China, as fair and loyal partners. They also emphasize economic partnerships through themes of “mutual benefit,” “non-interference,” “South-South cooperation,” and “win-win cooperation,” constructing a façade of positive development while promoting authoritarian governance norms and anti-democratic sentiments.

Beijing’s narrative warfare operates across multiple domains, each employing specific mechanisms to foster an environment conducive to the adoption of Chinese narratives while discouraging open opposition. The goal is to achieve perception dominance – the ability to influence and control how situations, events, and narratives are interpreted by others.

Political Influence and Party-to-Party Relations

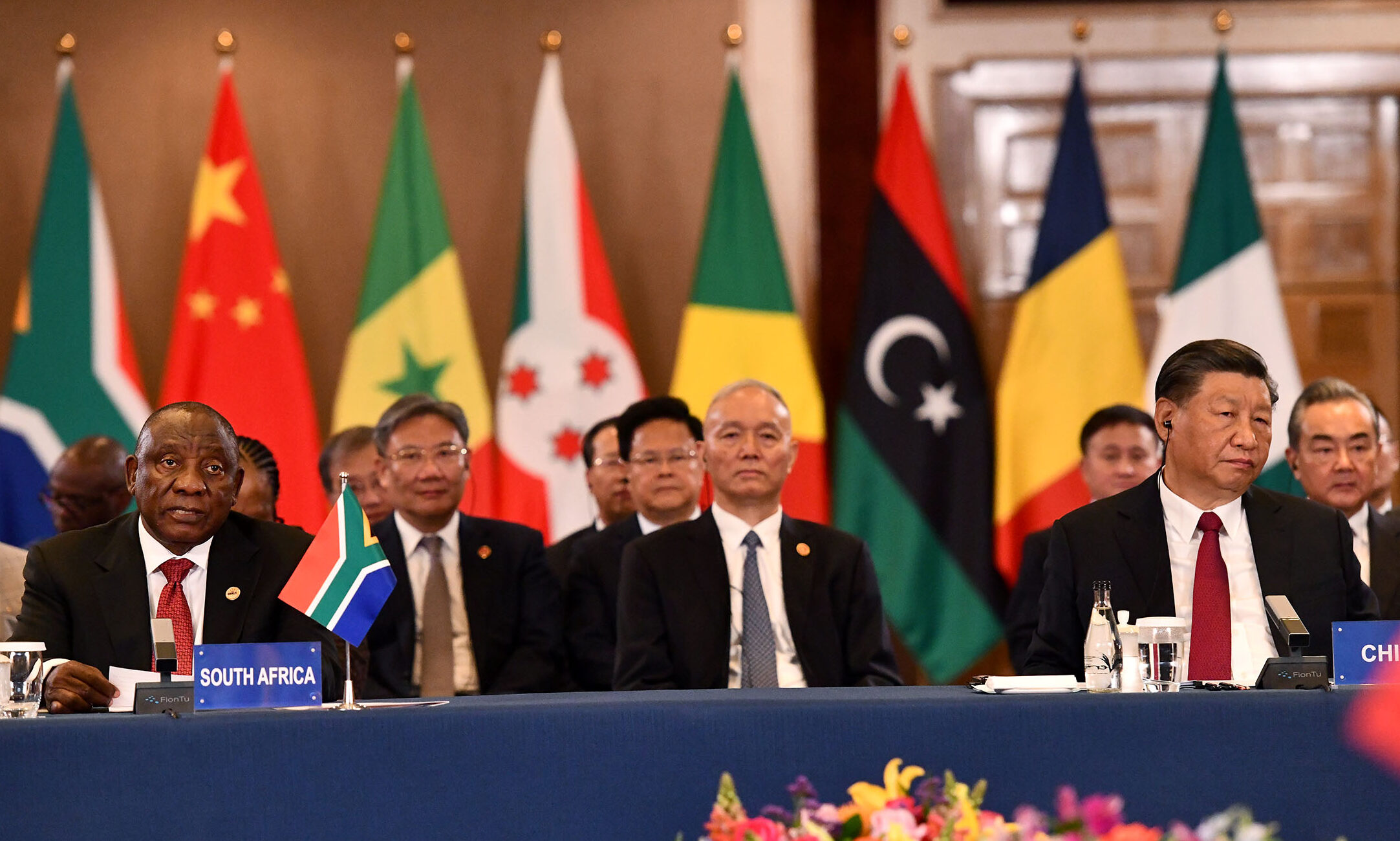

A key aspect of China’s strategy is its political engagement, where the CCP promotes its governance model through party-to-party exchanges. The International Liaison Department of the Communist Party (ILD) has conducted over 600 exchanges with more than 60 (mostly ruling) political parties in Africa, including bilateral and multilateral engagements, cadre training, and the provision of material and expertise support.

Multilateral exchanges enable the CCP to position itself as a “central node” within China’s African networks, encouraging a “group-think” mentality among the participating political elites. The CCP also trains over 2,000 African political cadres and several hundred local government officials annually, aiming to familiarize local political elites with China’s approach to economic development and political governance.

Additionally, the CCP funds and constructs government and party buildings, hospitals, and schools. A notable example is the $40 million construction of the Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Completed in February 2022, the school serves as a hub for disseminating China’s governance model and political ideology among African elites.

Media Expansion: Shaping Perceptions

Chinese state media in Africa counter pro-Western narratives by promoting a positive view of China’s presence on the continent. Through partnerships with African media houses and journalists, China integrates its perspectives into local media markets while acquiring stakes in key news outlets to influence their editorial practices. Beijing’s strategy includes ownership and control of media and ICT infrastructure, as well as journalists training programs. The Chinese media presence in Africa is also strategically calculated and ideologically driven, aimed at persuading locals to adopt Chinese perspectives on global affairs while capitalizing on a nascent domestic disinformation ecosystem, often using local influencers who communicate in native languages.

In addition to promoting political, diplomatic, economic and security partnerships, particularly in Francophone West Africa, China deploys a narrative influence strategy that weakens the public perception of France and the United States. Given that journalism does not always provide a sustainable income, some local journalists may also accept funds from Chinese sources, increasing the likelihood that they will follow and disseminate Chinese narratives while self-censoring on topics that undermine them.

Two primary types of Chinese actors operate in this sphere: CCP cadres posing as professional journalists and actual journalists. The role of CCP cadres is to evaluate content from a political point of view. They are frequently tasked with making editorial decisions while overseeing the work of both Chinese and African journalists and determining which content is suitable for public dissemination and which should be reserved for government and party actors.

Content produced in Beijing and disseminated in Sub-Saharan Africa is another mechanism through which Chinese actors spread the CCP narratives. Many countries, including Kenya, South Africa, Zambia, Ghana, Nigeria, and Zimbabwe, have signed media cooperation and content-sharing agreements with Chinese state media agencies, facilitating the proliferation of Chinese political narratives within these countries. In some cases, Chinese state media outlets disseminate content in Africa that could be easily classified as misinformation or disinformation, as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In effect, Chinese actors have developed the ability to appeal to African audiences. For instance, in South Africa, there are not only state media agencies but also media operations run by Chinese residents, which focus on narratives tailored for local audiences. Even local media outlets sometimes publish copies of news from Chinese sources, which criticize Western elites. Moreover, Chinese officials strengthen the capacities and local credibility of African journalists through fully funded trips, workshops, immersion seminars, and scholarships for degree programs in China, with the participants expected to communicate narratives favorable to China upon their returns.

China is engaged in narrative warfare against the West, which makes top-down information control crucial not only in China but also in Africa. Criticism of Beijing is thus not allowed in China and should likewise be avoided in Africa. Journalists and media companies that disseminate information unfavorable to Chinese narratives and officials are targeted by the state-controlled media. In this way, Chinese authoritarian practices are gradually spreading in Sub-Saharan Africa, driven by the rapid expansion of Chinese state-controlled media. In Kenya, the Chinese embassy and companies have pressured local media outlets over what they deemed as reporting critical of Beijing. And while most newspapers have withstood such pressures, many individual journalists are reluctant to jeopardize their relationship with Chinese officials, who offer sponsored trips, gifts, and other incentives. China’s influence in Africa thus facilitates the export of repressive practices that undermine freedom of speech, expression, and access to information, particularly to countries with authoritarian regimes and weak democratic institutions.

Digital Expansion: Controlling the Information Space

Another mechanism through which Beijing fosters local conditions for the acceptance of its strategic narratives is the export of Chinese information and communications technology (ICT). In this way, Beijing promotes digital authoritarianism focused on the provision of digital infrastructure that can be used to suppress freedom of expression and dissent. Chinese technology, combined with governance norms, enable the control of information space through online censorship, including website blocking and Internet shutdowns during elections or other political events.

China is thus promoting political illiberalism not only through investments in digital infrastructure, but also the use of legal frameworks and censorship techniques designed to establish a technology-enabled authoritarian governance. Beijing’s digital expansion also involves manipulating ideas, political perceptions, and electoral processes, with policies like data localization playing an increasingly important role in building narrative power. The proliferation of connected mobile devices and digital media provides opportunities for Chinese narratives to reach an ever-growing number of news consumers.

The provision of sophisticated ICT is a key selling point for partnerships between African and Chinese news media organizations. Moreover, expanding the presence of Chinese state media and diplomatic accounts on social media platforms has become a priority for Beijing as part of its efforts to counter information unfavorable to Chinese narratives on issues such as human rights, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the COVID-19 origin. In Kenya, for example, Chinese diplomats have used social media to promote disinformation and label factual yet unfavorable information about China as misinformation. While Beijing’s strategy primarily focuses on issues tied to its core interests, its narrative power on social media is based on propaganda, disinformation, and censorship.

The Digital Silk Road, announced in 2017, is a response to the perceived Western dominance in global ICT infrastructure, which the Chinese leadership equals with “network hegemony” of the US. As a consequence, the ICT industry is frequently mobilized to enhance China’s national power by creating a new tech infrastructure favorable to Beijing, believed to be critical for maintaining Chinese core values and controlling its strategic narratives.

Economic Influence and the Belt and Road Initiative

China’s presence in Sub-Saharan Africa challenges the EU and the US by offering an alternative to their liberal democratic development models. By providing African countries with an alternative approach to economic development, China has created ample opportunities for disseminating narratives that capitalize on existing anti-Western sentiments while arguing that liberal democracies are economically ineffective. Indeed, China has been able to offer a vision of development that is attractive on multiple levels: not only does cooperation with China reduce global pressures to adhere to liberal democratic norms, but it also promises swift results while maintaining a peacekeeping presence.

Moreover, acceptance of Chinese narratives can lead to various economic benefits for relevant states, including access to soft loans, quick service delivery, affordable goods, and funding for peacekeeping operations. Beijing thus integrates economic and political objectives into its narrative warfare through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and telecom companies. Initially focused on trade and investment, people-to-people exchanges, and financial cooperation, the BRI has increasingly emphasized infrastructure development, which in turn facilitates trade, investment, cultural exchanges, and public diplomacy programs.

Cultural Influence and the Promotion of Chinese Culture

China’s cultural engagement in Sub-Saharan Africa is driven by narratives promoting CCP-defined Chinese culture to gain perception dominance and undermine the liberal democratic worldview. Key mechanisms include education programs and cooperation, most notably through Confucius Institutes.

Chinese officials view education as a means to promote China’s model of economic development among African students studying in China, expecting them to act as cultural ambassadors upon their return, thereby creating cultural bridges between Beijing and Africa. In parallel, Confucius Institutes and Classrooms serve as central platforms for Chinese language-based cultural diplomacy, which makes them vital tools in China’s narrative warfare.

Security Cooperation and the Dissemination of CCP’s Narrative Power

In the defense domain, the CCP’s narrative power is largely accomplished through security and defense cooperation, namely through different hierarchical and vertical networks such as local civic and police cooperation centers. These serve as platforms for interpersonal and ideological exchanges, creating opportunities to shape the security information space. Indeed, security cooperation has become a key aspect of China’s presence in Africa, often involving private security companies.

Beijing’s security engagement is linked not only to narrative power, but also to political influence and military professionalization. Chinese Civic and Police Cooperation Centers – also known as Chinese Community and Police Cooperation Centers or Chinese Safety and Civil Cooperation Centers – have expanded across Africa since 2004, when the first such center was established in South Africa. Several Sub-Saharan African countries also engage in cooperation and police engagement with Chinese security officials, which has narrative implications. The schools and centers are marketed as public welfare organizations designed to support local governance, law enforcement, and local people by fostering economic growth, to which end they also promote Chinese norms and narratives about the Chinese governance model.

Implications for Africa and the West

China’s strategic narratives seek to justify its presence in Sub-Saharan Africa. These narratives are disseminated across multiple domains through various mechanisms, including state media, infrastructure projects, cultural diplomacy, and security cooperation. For instance, Chinese state media activities in the information domain interact with and reinforce the activities of Chinese actors in the economic, political, cultural, and educational spheres. And while these activities may appear fragmented, they ultimately form a coherent and holistic effort to advance Beijing’s narrative warfare.

China’s growing narrative influence in Africa has implications for both the continent and the Euro-Atlantic community. By undermining liberal democratic norms and facilitating the proliferation of its authoritarian governance model, Beijing fosters hybrid threats that extend beyond Africa. China strategically exploits cultural similarities between African and Chinese civilizations to build feelings of reciprocity, mutual optimism, and acceptance of Chinese narratives, which are then used to increase its economic, political, and security footprint in Africa. It also uses anti-Western sentiments to prevent local populations from perceiving benefits in cooperating with the US and the EU.

Ultimately, China’s political influence is deeply intertwined with its economic, cultural and security engagements. BRI projects enhance public diplomacy efforts, whereas Chinese state media organizations promote perspectives favorable to Beijing and its growing international influence. Moreover, while publicly framed as fostering regional peace and long-term stability, a major goal of the expanding security cooperation is to counter any interference from outside.

Written by

Daouda Cissé

Dr Daouda Cissé is a researcher and lecturer specialized in China studies and Africa-China relations. He is currently affiliated with LASPAD (Laboratoire d’Analyse des Sociétés et Pouvoirs / Afrique Diasporas; in English: Centre for the Analysis of Societies and Powers / African Diasporas), Gaston Berger University, Saint-Louis, Senegal. He was a senior researcher at the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS), and an associate at Megatrends Afrika from April 2022 to March 2023. In 2021, he was a visiting scholar at National Chengchi University, Taiwan. Prior to that, he worked at the China Institute, University of Alberta, Canada, and the Centre for Chinese Studies (CCS), University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. He holds a PhD in economics from Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, Wuhan, China.

Marko Pihl

Marko Pihl is a doctoral researcher at the Centre for East Asian Studies at the University of Turku, specializing in China’s foreign policy. His research focuses on the CCP’s party-to party diplomacy in Africa and its role in shaping political alliances and strategic partnerships.