When announcing the state of emergency in Serbia on March 15 in response to the COVID-19 outbreak, Serbian president Aleksandar Vučić declared the notion of European solidarity non-existent, “a fairy tale on a paper”, while praising China as the only country capable of helping Serbia. He added that he had sent an official letter to Chinese President Xi Jinping asking for assistance, calling him not only a “dear friend”, but also a “brother” of the Serbian nation. When the first airplane carrying medical supplies and personnel landed in Belgrade a week later, Serbian President Vučić himself greeted the arriving Chinese doctors and, in a gesture of adulation, kissed a Chinese flag.

His words have attracted widespread attention and sparked debate on how badly the EU had undermined its position in the region through its initial ban on exports of medical equipment beyond its borders, including to the Western Balkan countries, and whether China is in the process of replacing Russia’s prominent position in Balkan affairs – which would represent a major geopolitical shift in this traditionally fragile region.

No Seismic Shifts

Looking at Vučić’s words, some months later, it seems that the state of play in the Balkans has changed much less than many alarmed observers feared. It also seems Vučić’s grandiose statements about China themselves mischaracterized the degree to which China’s actions outpaced those of other traditional partners. Indeed, Russia, Turkey and the US became involved rather quickly and even the EU eventually stepped in, offering an unprecedented €3.3 billion to help combat the coronavirus pandemic in the region.

These tumultuous developments and shifting positions have, however, demonstrated the flexibility and inventiveness of China, Russia and Turkey (which also swiftly provided active assistance), as well as how vulnerable the region is today.

After slowing the spread of the virus in its territory, China embarked on a massive PR campaign, offering assistance and sending medical equipment and experts to various countries worldwide. The fact that this “assistance” often took the form of expensive commercial contracts and that many of the masks and other equipment provided were of poor quality and unusable was effectively covered up by the noisy PR campaign accompanying these deliveries

Indeed, the Western Balkans have received a strong dose of what has come to be known as China’s “mask diplomacy” aimed at strengthening Beijing’s regional posture, positioning China as a responsible global player and distracting from the CCP’s central role in the spread of its coronavirus outbreak.

The first supplies landed in Serbia on March 21 and smaller deliveries to other Balkan countries followed suit. Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia and Montenegro all received some Chinese medical supplies during April. Only Kosovo, which is not officially recognized by China, was left out of Chinese largesse. Despite the fact that the actual value of the assistance has generally not been disclosed and remains rather obscure, the portrayal of China as a close friend of Balkan nations was carefully crafted and promoted by Chinese embassies and media in the region, as well as by many local media outlets, in Serbia especially in Serbia the pro-government ones.

Aircraft carrying Chinese medical supplies were ostentatiously welcomed at the airports by the highest political elites of countries involved. The new narrative of “brotherly relations” introduced by Vučić was further boosted by pro-government media and powerful imagery. Billboards paid for by a pro-government tabloid Informer, for example, had a portrait of Chinese President Xi Jinping against the backdrop of a Chinese flag with the words, “Thank you, Brother Xi”.

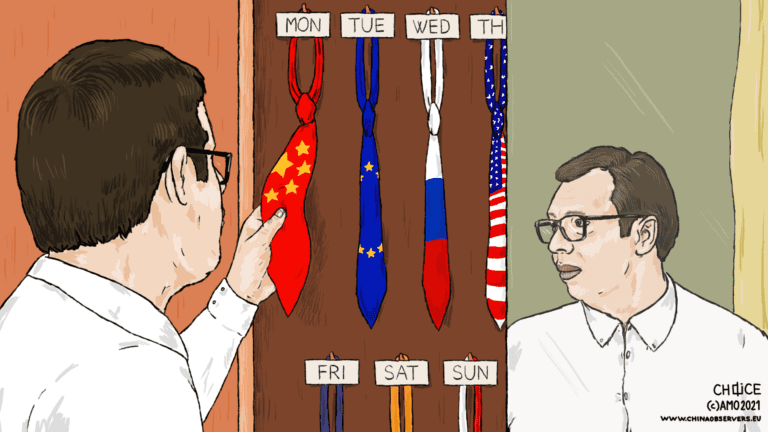

Until recently, the “brotherly” narrative of Serbia was reserved for Russia – its traditional close ally. Many commentaries have, therefore, speculated about a significant geopolitical shift in the priorities of certain Balkan states and China’s effort to usurp Russia’s leadership. Yet with the coronavirus-related battle over the “hearts and minds” of the Balkans receding and the situation largely returning to the status quo, it seems that these initial concerns were overblown.

Pro-Chinese statements of the Serbian President have been directed both at local audiences, among which China and Chinese investments are very popular, and at his EU counterparts. Political analyst Vuk Velebit suggested that China has overtaken Russia as Serbia’s greatest ally because Vučić understands that Europe takes China much more seriously. A senior Balkan expert, Dimitar Bechev, similarly asserts that the seeming shift of positions is not necessarily permanent, but rather context-dependent. Other external actors traditionally present in the region, specifically Russia, Turkey and some of the Gulf states, also promptly followed China’s chess moves and provided medical assistance of

their own to partners in the region in an effort to shore up their stakes in the region.

This analysis leads to the conclusion that the recent geopolitical developments in the Western Balkans related to the COVID-19 crisis are not resulting in any seismic shifts in the direction of the region. Instead, we are seeing the continuation of a long-term trend of the intensified efforts of external powers to strengthen their respective footholds in the region, which both geographically and politically represents a gateway to the EU. While COVID-19 made visible the rising Chinese footprint in the region (see more at balkancrossroads.com) and its potential to take center stage, it has also shown that Russia and Turkey are not yet willing to cede ground – offering their own assistance to their local allies and exploiting the situation for their own geopolitical interests.

The early welcoming gestures made by local political elites towards these external powers also confirmed another long-term and potentially hazardous trend – the rank opportunism of Balkan leaders in fostering foreign allies. Another crisis could bring different challenges and a re-ordering of positions, but it is clear from these recent events that external actors are eager to exploit skilfully every opening they see in the region to strengthen and improve their respective positions there.

The EU Missing in Action

In addition to exposing the vulnerability of this politically fragile region to foreign influence, the crisis has also revealed that delayed or reluctant EU support, and the problematic perceptions that this reinforces in the region, has the potential to complicate rapidly existing alignments with other actors and undermine the EU’s objectives in the region, including regarding the credibility of the region’s path to EU membership.

This experience should provide a strong impetus for improved European vigilance and demonstrate the need to pay close attention to all that is happening in the Western Balkans. Even when the pandemic eases in the upcoming period, the region will inevitably face the harsh and long-term social and economic consequences of months of national lockdowns. The next crisis, which could be economic and much deeper than the current one, will present another opportunity for foreign powers to exercise their influence over the region. The EU should be prepared for such a scenario and step in promptly and decisively before China, Russia or Turkey move to do so. Otherwise, it could be too late for the EU to keep this volatile neighborhood stable and more democratic than not.

This is an adapted version of PSSI Perspective 1 written as part of the project ‘Western Balkans at the Crossroads: Ways Forward in Analyzing External Actors’ Influence,’ led by the Prague Security Studies Institute. For more information, visit: www.balkancrossroads.com.

Written by

Barbora Chrzova

Barbora Chrzová is a Program Manager at PSSI. Her research interests include politics and society in the Balkans and Putin’s Russia with a special focus on the politics of identity and propaganda.

Petr Čermák

Petr Čermák is a project coordinator for the Prague Security Studies Institute, a PhD candidate in International Relations at the Faculty of Social Studies of Masaryk University in Brno, and junior researcher at the Faculty of Social Sciences of Charles University in Prague. His research is focused on the role of ethnic politics and power-sharing mechanisms in post-conflict areas of the Western Balkans, with a special emphasis on its local level dimensions. He has conducted extensive field research in different regions of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia.