Central Europe cannot sleepwalk into the CAI without a proper debate. German investments in China may negatively affect the beneficial status quo of Germany-CEE economic integration.

“What is good for German automakers is good for Central and Eastern Europe” is an argument often heard in Central and Eastern European (CEE) debates on the EU’s Comprehensive Agreement on Investments (CAI) with China. This argument refers to one of the most important economic relationships that the region is involved in – that with Germany’s global industrial giants.

The CEE nations serve as the economic backbone of the German industry, tightly linked to it within the global value chains. After the region joined the European Union in 2004, it was flooded with German investment and local companies managed to fill very specialized parts of German value chains, particularly within the critical auto industry. Taken together, the Visegrad Four (V4) countries are Germany’s most important global trade partner, both for imports and exports.

Factories and component suppliers located in the CEE region enable the German economy to compete globally, providing cheap and high-quality inputs, based on geographical proximity and access to a skilled workforce. In turn, CEE’s trade with the ex-EU world is often conducted by producing intermediate goods within the German value chains. Components are integrated into final products in Germany and then re-exported to other countries, including China. Much of the V4’s imports from China reflect a demand for components of foreign factories located in the region. This triangular trade is a key source of CEE countries’ persistent trade deficit with China, usually balanced by huge surpluses with Germany.

What’s in it for CEE?

This intimate relationship with the German industry is perhaps the main channel through which CEE can be impacted by CAI. The immediate benefits for the region will be limited because of a simple reason – Central European companies do not invest in China on a large scale.

The CEE region has very few global champions able to capitalize on the market-opening achievements of CAI in health, cloud services, telecommunications, R&D, and finance (with few exceptions, such as the late Petr Kellner’s PPF empire that is already operating in China). As pointed out by a recent report authored by the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM), the agreement does not contain any specific provisions for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). On the contrary, some of the crucial provisions of CAI – such as those in the e-mobility sector – apply only to very large investments of $1 billion or more, a scale out of reach for most CEE companies.

Germany’s stake in the CAI, on the other hand, is evident. It is the EU’s largest investor in China that generated FDI inflows larger than the rest of the EU combined for most of the past five years. Berlin was the main driving force behind the conclusion of the CAI in late 2020, despite huge political controversies surrounding the deal. Although the mood in Berlin is slowly changing, with many important stakeholders pointing at challenges coming from China, the conclusion of the CAI exemplifies the influence that industrial giants still exert over Germany’s foreign policy.

It should therefore be stressed that, from Germany’s perspective, the CAI is merely reinforcement to a very comprehensive bilateral investment cooperation with China. In fact, some of the provisions offered by China in CAI were already granted to German companies individually, usually during Chancellor Merkel’s meetings with PRC leaders. This concerns especially the automotive industry which – as it happens – is also the backbone of the economic relationship between the CEE countries and Germany. Given the scope of cooperation, as well as China’s determination to have Germany on its side on global issues, bilateral cooperation will remain dynamic regardless of the CAI’s ultimate fate.

China’s Domestication of German Value Chains?

Therefore, the question of how and to what extent Germany’s increasing investments in China, possibly enhanced by a ratified CAI, will impact existing production networks involving CEE nations necessarily arises.

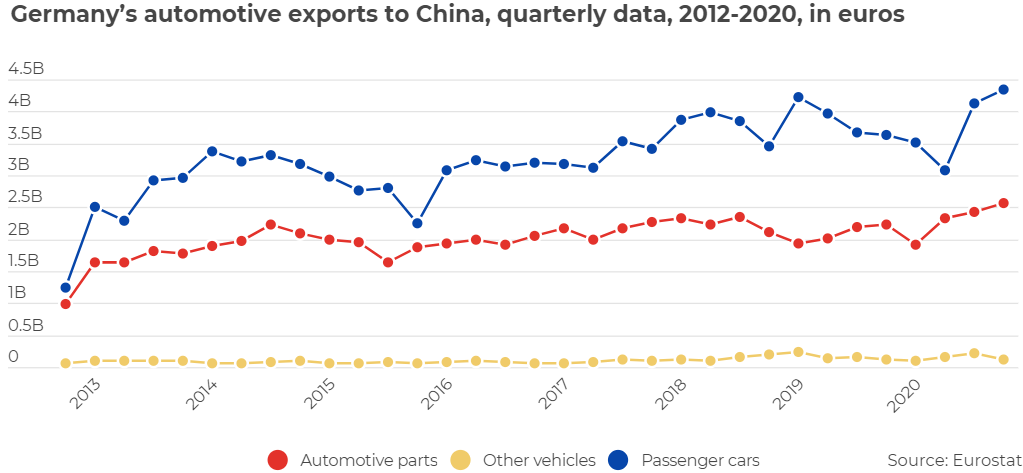

First of all, responding to this question will most probably lead to further regionalization of German value chains in China, forcing CEE component suppliers to follow German investors into the Far East. Every quarter, German automakers export €4 billion worth of passenger cars to China, with an additional €2.5 billion in automotive parts (see Chart 1 below) – all with considerable inputs from Central Europe. It is doubtful that all of that production will migrate to China after CAI, but new opportunities (such as allowing big German companies to have full ownership of factories, not just 50%) will encourage such moves.

From the point of view of German automakers, it makes perfect sense, as they become more competitive while producing locally. However, such a development may lead to a reshuffling in the network of components suppliers. Those include not only subsidiaries of German companies, but very often independent SMEs coming from CEE, specialized in the production of very specific components. If final production lines are moved to China from Europe, existing CEE suppliers will be forced to move along with them – or risk being replaced by Chinese competitors that enjoy broad support from the PRC.

In other words, signing the CAI may in fact push some CEE companies to invest in China while not enjoying the preferential treatment that China offers to the largest German automakers. Being still subject to regulations such as the requirement to form joint ventures with Chinese partners, they face bigger risks of IP theft and forced technology transfers – that most probably will not be fully eliminated by the CAI. The worry of being replaced by Chinese competitors, by the way, is also shared by the Mittelstand, the German medium-sized businesses that also participate in the value chains of industrial champions.

Competing for German FDI

The second possible economic effect of the CAI is more general and refers to the competition between CEE and China to attract production-oriented foreign direct investments. There has been a lot of talk in Central Europe about moving production of crucial components from China back to Europe, driven by geopolitics, pandemic disruptions and the simple fact that China is no longer that price-competitive. The recent announcement of Germany’s electro-machinery company Bosch that it will expand production in Poland while reducing it partially in China fits this broader picture.

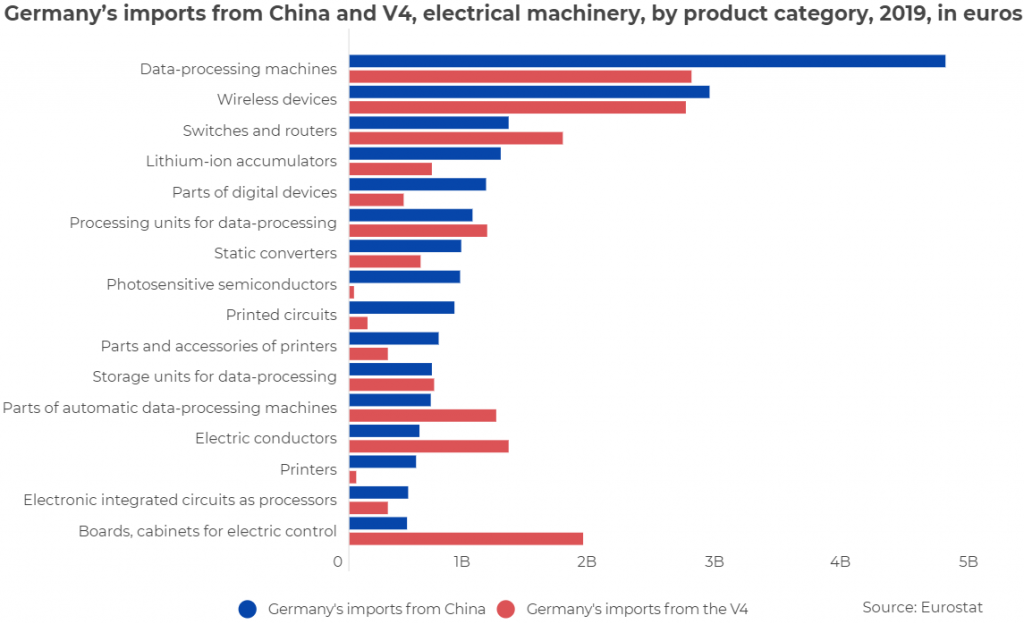

A quick look at the structure of Germany’s imports from China and the V4 in this sector (see the chart below) shows that the competition is fierce. In thirteen out of sixteen top product categories of China’s exports, there are corresponding V4 exports of comparable value (China dominates fully only in photovoltaics, printed circuits and printers). While those broad categories might not include identical products, they reveal that the V4 holds a very similar profile in terms of human capital, know-how and supplier base, with a potential to replace China in many parts of the value chain.

Still, FDI relocation is a two-way street, and CEE countries should keep that in mind. In some respects, the CAI and increasing bilateral cooperation between Beijing and Berlin are China’s attempts to counter reshoring trends, or even reverse them. China is also working hard on integrating its more price-competitive inland provinces with European production networks, particularly by developing EU-China railway connections that are used extensively by German automakers.

CEE still retains huge advantages vis-à-vis China coming from the geographical proximity to Germany and the EU common customs area. Nonetheless, the region should brace itself for increased competition from the Far East, should CAI induce a new wave of German investments in China. Central Europe should not sleepwalk into CAI without a proper debate. More German investments in China may affect the beneficial status quo of Germany-CEE economic integration, at least partially.

At a minimum, regional governments should get ready to counter potentially negative trends, particularly by supporting local suppliers to stay competitive within the German value chains and by adjusting their FDI policies. CEE capitals should also work on EU policies that could offset the negative economic impact, for example by safeguarding CEE companies’ participation in the EU’s “strategic reshoring” agenda. Within the broader debate on whether the EU should ratify CAI, this adds another argument on the liability side of the deal — along with issues of human rights, increasing EU’s vulnerability to China’s economic coercion, as well as tensions in the transatlantic relationship.

Written by

Jakub Jakóbowski

J_JakobowskiJakub Jakóbowski is the Coordinator of the Connectivity in Eurasia project, as well as a Senior Fellow at the China Programme at the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW), a public think-tank based in Warsaw.