Uncovering the Patterns of Chinese Investment in Southeast Europe

As China seems to be changing its preferred model of investment in Southeast Europe, a closer look at Chinese economic engagements over the past decade shows different motivations and varying role of local agency.

In the beginning of the previous decade, Chinese outbound foreign direct investment (FDI) in Southeast Europe (SEE) experienced significant growth, presenting new opportunities and challenges for the region. However, amidst a decade of soaring Chinese outbound FDI across the region, a nuanced exploration unravels diverse investment dynamics from one SEE country to another.

Hence, it is important to ask the following questions: are there any distinguishable investment patterns, and if so, what are the key driving forces behind Chinese commercial investment in the SEE? Moreover, does China’s actual economic footprint in the region live up to the hype surrounding Chinese investment in the media?

This article is based on our recent study, aiming to provide a comprehensive analysis of Chinese FDI in SEE between 2012 and 2022, exploring investment patterns, trends, drivers, ownership structures, and geopolitical implications.

In doing so, we adopted a multilevel approach, attempting to make explicitly clear that trends in Chinese outbound FDI cannot be examined in a vacuum. It is essential to take stock of the interaction of the domestic-driven factors with the external driving forces, shaped by third factors, including geopolitics, as they all together constitute Beijing’s investment priorities. This multilevel approach can help us not only explain past patterns but also outline future trends concerning the volume, sectoral focus, and implications of Chinese outbound FDI in the region.

Driving Forces Shaping Chinese FDI in SEE

The volume and type (greenfield, brownfield, M&As) of Chinese FDI in SEE is influenced by a combination of domestic priorities, the country’s economic model, and strategic calculations. Under the leadership of President Xi Jinping since 2013, the Chinese government has tightened control over the domestic economy, further blurring the lines between private-owned enterprises (POEs) and state-owned enterprises (SOEs). This consolidation of power has led to a greater role for the state in shaping investment preferences in line with the Communist Party’s priorities.

One significant driver of Chinese FDI in SEE is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which aims to enhance trade connectivity and infrastructure development along the ancient Silk Road routes. SEE countries, including Greece, and Serbia, are strategically located along these routes, making them attractive destinations for Chinese investment. The BRI also serves as a platform for China to expand its geopolitical influence and secure access to key markets and resources.

Chinese FDI in SEE varies across countries, reflecting specific factors within each nation. Slovenia, known for its advanced technology sector, attracts Chinese investment primarily through mergers and acquisitions (M&A) deals driven by profit motives. China’s focus on acquiring technology and innovation assets has led to investment in Slovenian tech companies. Notably, the €1 billion acquisition of “Outfit7”, an entertainment videogame company in 2017, by the Chinese high-tech POE Zhejiang Jinke is also the largest acquisition of a Slovenian company to have ever taken place.

On the other hand, Chinese enterprises in Serbia have made mostly greenfield and brownfield investment. Beijing’s increasing economic leverage in the country has often been translated into diplomatic support for a series of Beijing’s foreign and diplomatic policy priorities, illustrating a ‘transactional logic’.

Serbia is the country enjoying the lion’s share of Chinese investment in the region, accounting for 27 percent of its total FDI. In 2021, the total Chinese FDI including investment from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau reached €630.4 million, positioning it as the second-largest source of FDI after the EU, which invested €1.762 billion. The trend continued to strengthen in the first nine months of 2022, with Chinese FDI inflow surging to €491.5 million, surpassing the €401 million in FDI from the EU during the same period.

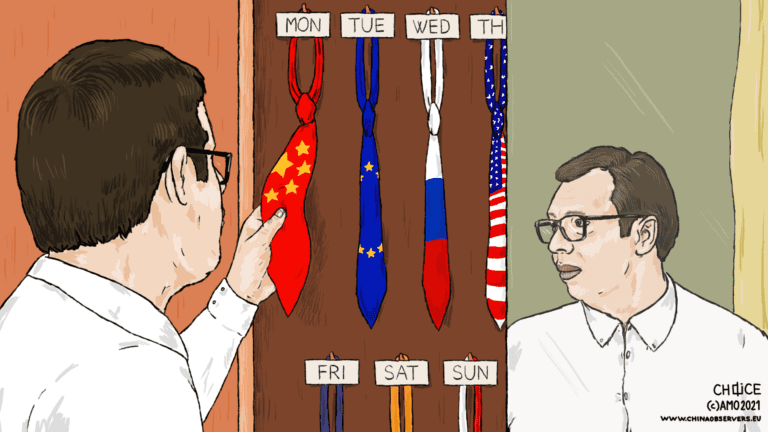

Notably, since 2012, Beijing has successfully secured Belgrade’s support for its main foreign policy priorities. Under President Aleksandar Vučić, Serbia has been a vocal supporter of Beijing’s “One China Policy” on Taiwan. Belgrade has also abstained from Western-led multilateral declarations criticizing Beijing’s treatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang.

Greece, strategically located at the crossroads of three continents, has also attracted Chinese investment in the last decade, particularly through acquisitions such as the Port of Piraeus. This investment showcases China’s efforts to establish logistical corridors and enhance trade connectivity between Europe, Asia, and Africa. The Greek port serves as a vital transit point, facilitating China’s trade routes and creating new opportunities for economic cooperation between China and the EU.

The Role of Local Agency in Attracting Chinese FDI

Despite often being overlooked, the local agency also plays an instrumental role in attracting Chinese FDI, with each country in the region presenting different trends and peculiarities driven by governments and political and business elites.

Serbia, for example, actively facilitates Chinese FDI, prioritizing job creation and indirect gains for local elites, often turning a blind eye to controversial foreign investment, criticized either for environmental reasons or alleged labor rights violations (eg. Linglong’s greenfield investment in Zrenjanin tire factory in 2018).

The two largest Chinese brownfield investments in the country in the most recent years, the mining Plant in Bor and the takeover of the Smederevo steel mill, both of which were made by Chinese SOEs, have attracted widespread criticism for their environmental impact as well as for alleged labor rights violations.

Serbia’s strategy is also aimed at securing Beijing’s ongoing diplomatic backing on matters of strategic significance for Serbia, as China is alongside Russia the only permanent member of the UN Security Council that does not recognize Kosovo.

In contrast, Albania, also an EU candidate state, takes a more lukewarm approach to cooperation with China. Albania, alongside Bosnia and Herzegovina, is the SEE country with the smallest inflows of Chinese FDIs, which has been in decline since 2014. It is also one of the non-EU states in the region (alongside Montenegro and North Macedonia) with the highest level of alignment with the EU’s foreign policy position and unlike Serbia, it is also a NATO member.

This is also reflected in the discourse of high-level politicians and officials in Albania, who have been much more reserved when expressing their views on cooperation with China. Albanian government officials have expressed dissatisfaction with the economic benefits derived from China’s 17+1 economic cooperation bloc. Last year, Prime Minister Edi Rama openly stated the lack of economic benefits from this cooperation. This stands in stark contrast to the Serbian public discourse on China, where officials express significantly more favorable views.

In general, the EU member states in the region have been less politically favorable towards Beijing with the exception of the Greek government’s block of an EU statement in the UN criticizing China’s human rights record in 2017, only a year after the two biggest Chinese FDI in the country took place. However, this has been more of an exception in terms of Greek policy rather than a rule. The New Democracy government in Greece has taken a more cautious stance towards China since 2019, particularly in light of China’s increasing rivalry with the US, with Athens actively promoting itself as a crucial ally of Washington in the broader region.

Constraints: The Limits of Chinese FDI in the Region

Currently, Chinese FDI in SEE faces several constraints that influence the volume and nature of investment. Since 2016, China has implemented restrictions on outbound capital flows, limiting its resources for investment with uncertain financial returns. Slowing economic growth and structural deficiencies within China have prompted a reassessment of the country’s economic model, restricting its foreign expansion.

Additionally, there is a mismatch between local supply in SEE and Chinese demand. Chinese enterprises, especially the private-owned ones, primarily focus on acquisitions of innovative tech companies in Western Europe, while SEE countries are mainly seen as low-cost destinations for labor-intensive industries. The lack of a well-developed technological ecosystem and limited innovation capacity in SEE limit the attractiveness of the region for Chinese tech-focused investment.

Moreover, the structural characteristics of local economies in SEE make the region of limited economic interest to Chinese firms except in cases where there are also political or diplomatic gains (e.g. in Serbia). At the same time, ad-hoc politicized decision-making can be a double-edged sword for FDI in the region with phenomena of corruption and political clientelism often weakening the economic rationale underlying these investments.

Keeping a Lower Profile to Avoid Scrutiny

The global context and various external factors, mainly the competition with the US being a crucial driver, are also increasingly shaping China’s broader geoeconomic priorities, including in SEE.

The restrictions imposed by the US on the exports of critical technology in 2018 prompted a rethinking of Beijing’s economic policies, prioritizing self-sufficiency in sectors of strategic importance. At the same time, the bilateral tensions and ensuing global polarization have led to a change of approach on the part of some SEE countries which has left Chinese investment less coveted and even less welcome.

Finally, the expansion of tighter screening regimes in Europe, in the context of souring EU-China relations is another constraining factor for Chinese FDI in the coming years, albeit with a limited effect in SEE, especially its non-EU states. The EU has become increasingly alarmed about potentially harmful strategic implications of foreign investment and takeovers, especially in critical infrastructure and technologies.

To overcome these constraints, Chinese firms and privately-owned enterprises (POEs) in particular, are increasingly resorting to minority investment and joint ventures with Western firms to make themselves more welcome in the region. These joint ventures and strategic partnerships with Western firms are likely to become a more common feature of Chinese FDI in the region in the years to come.

There are several such examples in recent years pointing to this direction. In 2019, the Mozura wind park project in Montenegro was inaugurated. In 2020, two Chinese SOEs joined forces with an Israeli company (MT Abraham) for the partial takeover of Aluminij in Bosnia and Herzegovina. This was followed by Yanfeng Automotive’s €30 million joint venture with the US-based manufacturer ARC Automotive in North Macedonia, launched in October 2022.

Nevertheless, once again, Serbia seems to be an exception to this pattern as Chinese investment is still on the rise with both greenfield and brownfield investment taking place in sectors such as mining, the metal industry, and the automotive industry.

In conclusion, the surge in Chinese outbound investment in SEE over the last decade is a result of a complex interplay between domestic priorities, factors related to the recipient states, and global economic dynamics. The varying responses from different countries in the region, such as Serbia’s strategic alignment and Albania’s cautious approach, highlight the nuanced nature of the situation. Moving forward, understanding these patterns and their implications will be crucial for policymakers in the region to navigate the opportunities and challenges posed by Chinese FDI.

Written by

Ioannis Alexandris

John_AlexandrisIoannis Alexandris is a political scientist working as a public affairs consultant focusing on political, macroeconomic, and regulatory risks in Europe. His research interests are focused on foreign policy, migration, geo-economics, and the intersection between politics and business. In the past, he has also worked as a trainee at the Council of the EU (Enlargement Unit) and as an interim Research Officer at the EU Agency for Asylum (EUAA).