With the reconciliation between Iran and Saudi Arabia, China might have paved the way for its more systematized involvement in the region.

The Iran-Saudi rapprochement facilitated by China is a big deal as it will mitigate competition between Riyadh and Tehran which has shaped the geopolitics of the Middle East over the past decade. The diplomatic breakthrough could have a profound influence on the Middle East touching upon the conflicts in Syria, Yemen, and the general security situation in the Gulf region. Moreover, it could indirectly pull China into playing a bigger role in the entire region.

The negotiations were ongoing for some time, hosted by either Iraq or Oman, but the fact that China apparently played a major facilitating role with the concluding ceremony held in Beijing speaks volumes about how China’s approach to its role in the world and the Middle East in particular has changed over the past months.

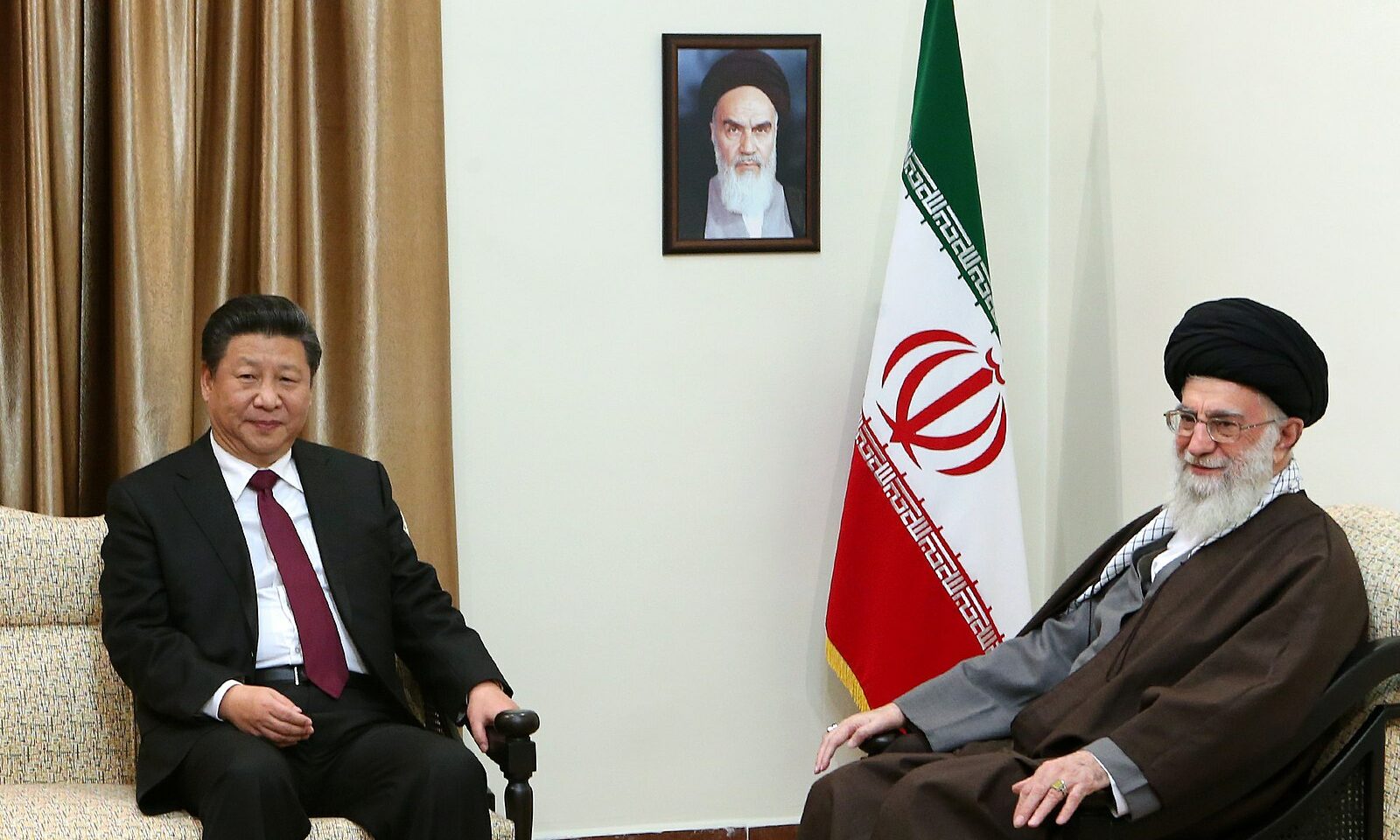

China’s rising role in the Middle East has long been in the making with the latest examples being a summit with the Gulf states held in December 2022 and the hosting of the Iranian president in February. Beijing has tried to carefully manage the different preferences and concerns of the regional actors in a difficult, but so far quite successful diplomatic maneuvering.

In a way, China has been pushed to play a more active role. Its growing economic ties with Saudi Arabia, the other Gulf States, and Iran (despite numerous grievances in Tehran) made China highly dependent on oil supplies from the region. Moreover, sporadic tensions between Riyadh and Tehran made Beijing vulnerable to potential regional conflagration such as the one in 2019 when drone strikes almost knocked out Saudi Arabia’s entire oil production industry. For China, stepping more directly into the security issues in the region has thus been a long-expected development.

Troubled Region

With the Iran-Saudi deal, however, there could also come dangers of overextension and potential dilution of China’s peacemaking efforts. The main dilemma for Beijing comes from Iran, which is unlikely to change its ambitions to dominate the region. Moreover, Tehran will also not abstain from pursuing its nuclear program. The Islamic Republic might de-escalate when it fits its immediate interests, but it will certainly not change its long-term foreign policy.

Nor will Saudi Arabia abandon its core security imperatives, including the maintenance of stability in the Gulf region and facilitating resolution to the conflicts in Yemen and Syria, which often goes against Iran’s interests. Moreover, Saudi Arabia’s close security ties (intelligence sharing, arms sales, and joint military exercises) with the United States as well as unofficial, but quite active contacts with Israel also represent a challenge for Iran.

It remains to be seen how China will manage highly combustible Iran-Saudi relations. It will require China to adopt a highly elastic diplomacy to quickly and skillfully adapt to rising challenges in the Middle East. One solution might be establishing loose but effective multilateral initiatives involving regular summits and forums. China already has a tradition of hosting regional summits. For instance, Beijing has engaged in this form of cooperation with Central Asian states where, obviously, there is no such enmity as exists between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Still, such an arrangement might be something Beijing might mimic when it comes to the Middle East. Indeed, it has been reported that a similar summit with the Gulf states, but this time along with Iran, will be held in Beijing later in 2023.

Eurasian Perspective

While many assume that China might be on its way to replacing the US in the region, the reality is more nuanced.

With the Iran-Saudi deal, quietly but steadily, a shift from a US-dominated Middle East to a multipolar geopolitical setting is taking place. The uncertainties around the US’ position in the region might have initially angered and perplexed the Gulf states, but increasingly, they see this as an opportunity to build a multi-vector foreign policy. They might still seek security guarantees from Washington, but beyond that, a geopolitically congested Middle East also has certain advantages.

The growing competition between the US and China paves the way for smaller powers such as Iran and Saudi Arabia to pursue a multivector foreign policy by building links simultaneously with several power centers and thus elevating their own regional status.

Not all countries are seeing the world order as undergoing bifurcation between China and the US. For many in the global South, choosing between Beijing and Washington is a non-starter. Rather, these countries seek their own agenda, which is influenced by what America and China want, but only partially. The growing role of China brings about a greater room for maneuverability, which has been absent in the Cold War era when a geopolitical dichotomy prevailed in much of the world. This is also how both Iran and Saudi Arabia embraced the idea of China as a peacemaker.

For Beijing, this could be a pivotal moment. However, for its designs to be acceptable, China also needs to stay clear of mounting a direct challenge against the US’ role in the region. Such an approach might scare off many of the Middle Eastern countries which still see the US as playing an important role in the region, not at least in the security sphere.

Zooming out, the Iran-Saudi Arabia deal should also be seen in the light of the recently introduced Global Security Initiative (GSI). Built on its success in the Middle East, China is now making moves in another direction, namely the seemingly intractable Russia-Ukraine war. Beijing already published its ‘peace plan’ for Ukraine and Xi is traveling to Russia and will probably talk to Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky this week.

Both the diplomatic victory in the Middle East and the forays into the war in Ukraine should be seen within a broader picture of China remodeling its position globally with the application of the GSI. Though the latter was received with skepticism, Beijing is quite intent on making the initiative work in regions beset by chronic conflict.

Chinese reconciliation efforts in the Middle East also fit into a much wider trend in the region where countries are reaching rapprochements with erstwhile rivals without the US involvement. For instance, Turkey normalized ties with the Saudis in 2022, and Qatar and its neighbors made initial moves to improve fraught relations in recent months. It is notable that these efforts are made amid distractions for the US, which China is cleverly using by filling in the emerging geopolitical vacuum. Too much responsibility, however, could be counterproductive, and for Beijing, it is critical at this stage to balance the expectations of local actors and its own interests.

Written by

Emil Avdaliani

emilavdalianiEmil Avdaliani is a research fellow at the Turan Research Center and a professor of international relations at the European University in Tbilisi, Georgia. His research focuses on the history of the Silk Roads and the interests of great powers in the Middle East and the Caucasus.