EU-China relations are changing rapidly, and so is the long-term outlook as seen from Europe. In a consultation on this fast-moving topic, European experts shared their views concerning the EU’s priorities, choices, challenges, and opportunities in its dealings with China towards 2030.

Altogether 171 China observers contributed to an expert survey on the future of EU-China relations published by the European Parliamentary Research Service. This included 21 China observers from among the EU institutions, 75 China specialists from European think tanks, and 75 China watchers from the European Guanxi youth network (most active in Spain and Italy). The responses reflect the considerations, insights, and advice of Europe’s China knowledge community on the EU’s approach to China towards 2030.

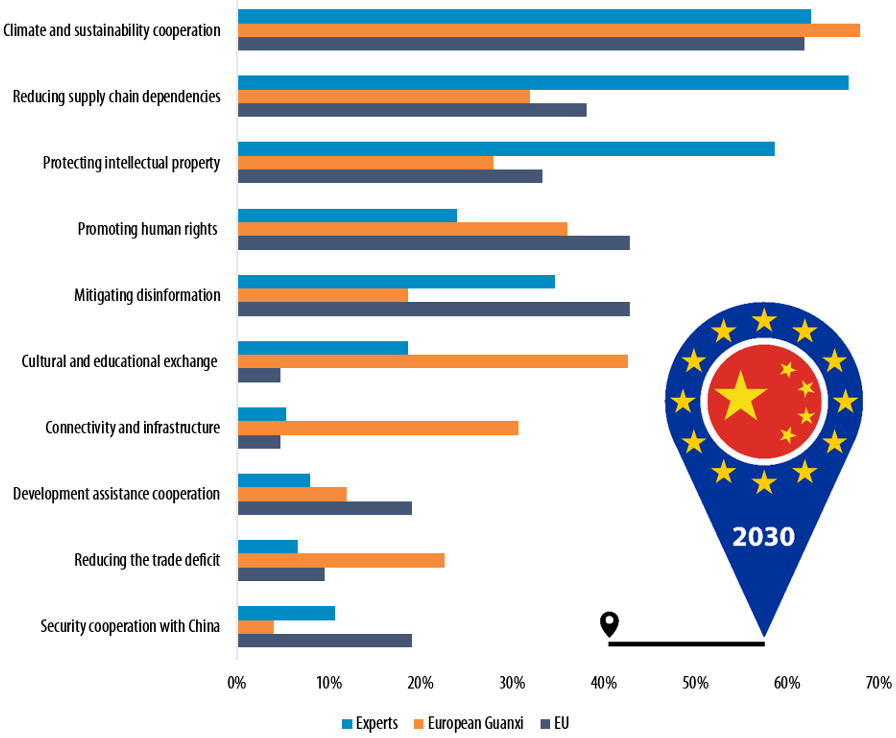

The priority areas for EU-China relations in the coming decade, based on how often they were flagged by respondents, are first, cooperation on climate and sustainability, and secondly, reducing supply-chain dependencies and protecting intellectual property (see figure 1 below). This shows that Europe’s China expert community is aware of both the risks and the need to cooperate with China where necessary.

Figure 1: Priorities for EU-China relations

Seeking Reciprocity

In terms of the trade agenda, respondents prioritized reciprocity in market access as an objective for the bloc’s China policy. Many respondents urged the EU to demand access to the Chinese market, including in trade and investment, by leveraging the threat of closing off the European market to China. Mitigating dependencies on Chinese products was a close second among the answers, reflecting the respondents’ strong concerns about supply chain security. In contrast, reducing the trade deficit came last with under 10 percent of responses.

The focus on reciprocity reflects the growing salience of the issue on the EU level. In recent years, the European Parliament expressed concern “about the increasingly unbalanced bilateral economic and trade relationship between the EU and China” and stressed that “rebalancing and a more level playing field are vital to EU interests,” including in the context of “the EU’s ongoing work in strengthening its trade toolbox.”

Regarding the EU’s approach to Chinese-financed infrastructure on its territory, most respondents favored the moderate option of more active regulation and providing alternatives. The second most popular option was to welcome Chinese-financed infrastructure in Europe, provided it complied with existing regulations, with only a fraction of respondents preferring to prevent or severely limit any Chinese engagement.

The issue has recently come under the spotlight when in July 2022, Croatia opened the €420 million Pelješac Bridge which was largely funded by the EU but built by a Chinese state-owned company, the same one that won the highway contract which caused a debt crisis in Montenegro. However, the project could be the last of its kind. The EU’s new International Procurement Instrument, which came to force in August 2022, will serve to block foreign contractors from countries that, like China, do not grant European bidders access to their own infrastructure market.

Views were more mixed on the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). Over two thirds of experts and over half of European Guanxi followers believe that the EU should use the freezing of the CAI as an opportunity to renegotiate the deal. On the contrary, the respondents from the EU institutions chose ratifying the CAI in the current wording as their most favored option, while it was the second most preferred course of action among European Guanxi followers. Experts, perhaps because of oft-cited concerns about the CAI’s incomplete human rights and sustainability standards and weak mutual enforceability prospects, were much more skeptical about this option and ranked abandoning the CAI completely as the second most favored option. Regardless of the different views on the topics, there is little indication that the CAI will be unfrozen any time soon, as each side refuses to move first to lift its March 2021 sanctions.

On technology, experts and EU respondents largely agreed that R&D cooperation with Chinese actors should be more actively regulated, while European Guanxi followers believed such collaboration should instead be encouraged. Only a small minority of respondents was in favor of severely restricting or preventing R&D cooperation. From 2016 to 2020, the EU paid for €500 million of the €630 million spent on the EU-China Co-Funding Mechanism for joint research projects, despite European researchers’ complaints about unequal access and the lack of reciprocity in information sharing in EU-China joint research projects. European policymakers and universities have accordingly become more critical and have started to introduce measures to better shield European research and technology when collaborating with Chinese researchers and companies. Large-scale Chinese funding of individual European researchers in crucial domains nevertheless continues largely unnoticed.

Concerning how the EU should approach Chinese financing or ownership of European media, most respondents from all surveyed groups supported EU monitoring and restriction of Chinese financing, rather than banning the Chinese involvement outright or not interfering with it at all. While European companies are unable to invest in Chinese media, Chinese investors are largely free to acquire European news services and other media assets. The CAI would have cemented this lack of reciprocity by assuring that Chinese media investors in most Member States be treated in the same way as the local entities, without improving access for European investors in China’s media sector, despite European parliamentarians’ concerns about European media outlets being targeted by Chinese mergers and acquisitions.

Security and Human Rights

Security is becoming a hotly debated issue in EU-China relations. Approximately 40 percent of the EU’s foreign trade passes through the South China Sea. For the moment, the Netherlands, France, and Germany have been the only EU Member States to have sent navy vessels into the area to assert their freedom of navigation or for military exercises, often jointly with the UK, US, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. Potential EU joint patrols with these and other partners in the South China Sea was another divisive topic, with almost half of the experts and EU officials suggesting that the bloc should consider doing so. About a third felt that the EU should even actively explore possibilities to proceed with the patrols. In contrast, European Guanxi followers, perhaps fearing an escalation of tensions with China, most often opted to never engage in such patrols, while keeping this open for consideration was the second most preferred option.

When it comes to how the EU should approach the deployment of 5G networks using telecoms equipment from Chinese vendors, the most moderate option of introducing regulations or additional security standards, rather than welcoming or outright banning Chinese involvement, came out on top among all three target groups surveyed. In January 2020, the EU adopted its 5G toolbox which cautioned against implementing 5G rollouts in Europe using companies from undemocratic countries that have strong links to, or can be pressured by, their government, which is interpreted as a clear reference to Huawei. In recent years, many Member States have moved to de facto ban or restrict Chinese telecoms from their 5G networks, often partly under US pressure to do so.

Human rights have long been one of the most divisive areas of EU-China relations, with tensions escalating after the 2021 reciprocal sanctions. Regarding how the EU should respond to Chinese human rights violations, most respondents advocated deploying EU solutions and instruments to actively deter them, while the more restrained option of simply remaining critical and denouncing the violations came in as a close second and was a favorite among the respondents from the EU institutions. To intervene less in Chinese human rights issues was by far the most unpopular option. In reality, the China-EU dialogue on the issue remains stalled, with the last high-level human rights dialogues held in 2019.

The EU-China SWOT Analysis

Respondents identified strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats for Europe in its relations with China in the coming decade. The strengths to be capitalized on included, by order of importance, Europe’s large economy and market access to be leveraged; Europe’s advanced technological capabilities; Europe’s normative power; and its international partnerships, hedging power, and global influence.

Figure 2: Word cloud of responses on strengths and how to capitalize on them

The main weaknesses pinpointed by the respondents were Europe’s internal divisions and weak common foreign and security policy (CFSP) mandate; its economic and technological dependencies on both China and the US; hybrid threats from Chinese influencing activity through media and communications; and a perceived lack of European expertise on China.

The experts mostly saw opportunities in cooperation with China on climate and innovation; promotion of European values and standards; Europe’s turn towards a more realist and strategic policy-making on China; and the potential for diversifying partnerships with third countries amid the US-China rivalry.

Finally, the most commonly identified threats concerned European disunity and policy-making inertia; hybrid and systemic threats including cyberattacks and disinformation; US-China geopolitical tensions; but also supply dependencies, infrastructure vulnerabilities, and falling behind China in technology.

The above indicates that European China experts are aware that Europe’s large single market, as well as its authority to regulate external commercial relations, could be considered its most useful asset in steering relations with China in a more advantageous direction. As also signaled by the assessment of priorities, high hopes remain for climate cooperation with China, despite such cooperation having stalled over the past five years. Finally, the perception of weaknesses and threats underlined the anxiety concerning Europe’s perceived difficulties in acting in unity in confronting geopolitical challenges posed by China, in large part stemming from the EU’s relatively underdeveloped CFSP mandate as compared to its much more robust economic competencies.

EU-China Outlook Towards 2030

Looking ahead towards 2030, European policy-making on China will likely gravitate further towards systemic rivalry through internal resilience building and external coalition formation against authoritarian interference. The economic competition will witness growing unilateral leveraging of European market access to improve economic reciprocity with China and international partnership diversification for improved supply security. Moreover, despite popular hopes, EU-China cooperation on climate and global issues risks stagnating further in the coming decade.

To what extent Europe will manage to improve its position vis-à-vis China and effectively respond to the challenges posed by Beijing remains uncertain. This will depend on a myriad of factors, not least Europe’s ability to develop pragmatic solutions, as also embodied by the upgrading of the EU’s trade instruments toolbox, as well as European leaders’ shared political resolve to apply these instruments effectively.

Whether EU-China relations continue spiraling towards rivalry and away from partnership, however, is largely out of Europe’s hands and will mainly depend on China’s own behavior in the coming decade, especially concerning Ukraine, Taiwan, and its willingness to work on economic reciprocity. Xi Jinping’s third term in office and China’s declared objectives for that period promise still more of China’s all-of-society securitization, economic decoupling, technological struggle, and assertiveness against perceived foreign threats. As seen from Europe, the outlook for Beijing’s future policy-making trajectory thus remains pessimistic. The EU’s capability to effectively respond to these challenges in this decade will to a great extent determine Europe’s future strength, prosperity, and security in the world.

This article derives from a study titled ‘EU-China 2030: European expert consultation on future relations with China‘ originally published on December 7, 2022, by the EPRS. The views expressed therein should not be taken to represent an official position of the European Parliament.

Written by

Kjeld van Wieringen

Kjeld van Wieringen is a Policy Analyst at the European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS) in Brussels, focusing on geoeconomic trends in EU-China relations.