Even as debates about the characterization of the Sino-Russian partnership continue, energy cooperation between the two grows in intensity.

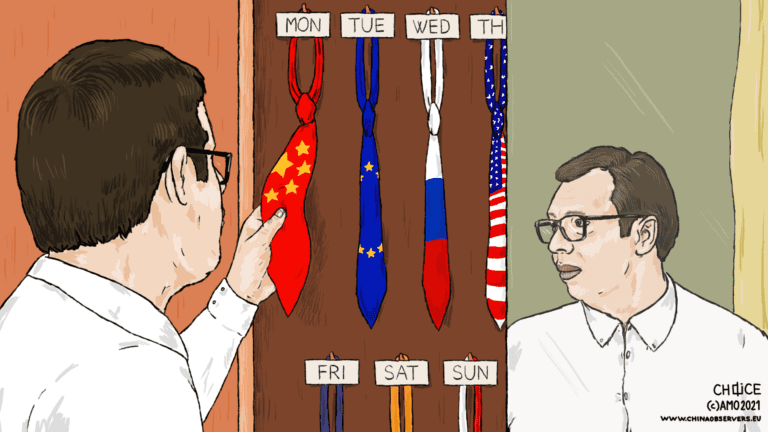

Amid the unfolding chaos of international relations, whereas the Western global order has plunged into a deep crisis and multilateralism shapes the future of regionally fragmented politics, the two biggest autocracies in the world are trying to display confidence and optimism about a new era in their strategic partnership. For Beijing and Moscow, such posturing provides both a mutual reassurance and an external message to the world that the two are close companions, and possibly a model of “dialogue and mutual trust.”

For many years, there has been an intense debate about the scope and quality of Sino-Russian cooperation, particularly since the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Over the last decade, there has been a shift from the “axis of convenience” and the “wary embrace” narratives towards the notion of an “axis-of-authoritarianism” and the “all-time-high” status of the partnership. This debate has only accelerated since the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

On one hand, the statement by the European Commission’s President Ursula von der Leyen during the latest EU-NATO summit confirms that the fears about a Sino-Russian entente re-shaping the international order to its benefit have become an openly discussed issue, also in Europe. On the other hand, the relationship is increasingly described as one of non-equal nature illustrated by the Russian President’s servile attitude towards Xi during their last meeting in Samarkand after several missteps of the Russian army in Ukraine.

Nevertheless, Chinese companies are now deemed to have offered some type of military and economic assistance to Russia, despite Beijing having publicly denied picking any side in the conflict amid US warnings of consequences. So, how can we make sense of this complicated and rather-obscure affair?

Beyond the generally shared opinion that the Sino-Russian partnership has gained strength because of the unintended consequences of Western actions against their autocratic opponents, a flourishing trend of research sees the Sino-Russian relations growing in complexity. To test this relationship it is necessary to be more empirical, closely looking at the path-dependent dynamics creating or hindering synergies between the two. Sino-Russian energy relations are a key focus in this respect.

The Prominence of Energy (In)security in the Partnership for a New Era

In fact, the collaboration on energy issues serves as the “anchor” of the strategic partnership, both in economic and political terms. According to Xi, the bilateral engagement on energy is “the cornerstone of practical cooperation” and an “effective force for global energy security” in a world torn by strategic competition.

Within this frame, the leadership in both countries plays an outsize role in determining the check and balances of the respective energy sectors. Indeed, personal ties provide a basis for successful bilateral energy diplomacy. To this extent, domestic policy is absolutely prominent in shaping the contours of joint energy projects between China and Russia.

Although in Putin’s case, the haste in getting his hands dirty is well-known to experts, and the last 12 months have only amplified this bad habit, there is far less conscience of how deeply the Chinese leadership is capable of influencing the industry’s policies.

In 2022, Beijing has heavily bet on renewables to accelerate the energy transition, increasing generation capacity to deal with winter and summer peak loads. According to the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), new wind and solar generation facilities account for over 55 percent of the total installed capacity in 2022, and their role in ensuring the country’s energy security is becoming “more and more obvious.” Still, air pollution inflated by climate change phenomena continues to darken Beijing’s skies, urging the government to bolster its ‘war on pollution’ commitments whilst picking up the lead in global transition policies.

And yet, both new and traditional energy sources must be considered critical for China’s energy security. Since 2021, when a series of intermittent outages and power rationing across the country was caused by a shortage of coal supply, the government has repeatedly intervened to stabilize its production and imports. Other than securing domestic coal production, Beijing has doubled down on fully tapping the domestic oil and gas potential, carefully managing the available and stored resources, and treasuring the importance of long-term partnerships, especially in the unstable global gas market. Here, China preferred to maximize pipeline gas imports rather than relying on prohibitively expensive spot purchases of LNG cargoes. With the economy hampered by stringent measures to curb the spread of COVID-19, oil and gas consumption fell for the first time in the last two decades in 2022.

The relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions will bolster Beijing’s oil demand and, as a consequence, setting the global demand to an all-time high in 2023. However, for the gas demand, the scenario is more uncertain as regulatory hurdles and pricing policies are hindering gas usage in the North of China, where temperatures are now plunging well below the seasonal average.

Now, it is quite clear that even though the goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2060 remains in place, strategic considerations, including revamping a stagnant economy after the umpteenth pandemic surge, will take precedence over Xi’s vision of “green mountains and blue waters” and the bold promises on cutting carbon emissions in the long-term. Here, the Sino-Russian energy cooperation has a clearcut role to play for Beijing’s strategic aims.

Cooperating to Ensure Global Energy Security?

Across the world, the structural changes in market conditions and the transforming nature of energy relations into much more politically dense settlements between nations are accelerating a reconfiguration of strategic energy axes, including the Sino-Russian one.

Russia’s priorities in the energy field are to stabilize the budget, diversify exports away from EU member states and renovate the import substitution programs launched after the first wave of sanctions in 2014. These ambitious goals will be key to maintaining the country’s primacy in the global energy order. According to Putin, Moscow will not cede its position and is ready to build new partnerships. Paradoxically, by rejecting the idea of selling price-capped energy resources, Russia is promoting itself as a stable and predictable energy partner; the linchpin of a brand-new Eurasian energy system. These are all assertions that will need to be proved in the years to come.

In the first nine months of 2022, Moscow has exploited a rather optimal scenario, using its energy assets as a powerful political tool, especially in the context of the EU-Russia gas trade. But now, the reality hurts. Western sanctions, including import bans and price caps, are biting into the Kremlin’s war chest. The volume of exports of Russian gas in 2022 ranked among the lowest since the collapse of the Soviet Union and Gazprom’s production was 20 percent lower than a year before. According to the company’s CEO Alexei Miller, it was a “very, very difficult year” for the Kremlin’s national champion, which witnessed a “total change in the energy markets,” to which it supposedly responded in a “very-well coordinated” manner.

From the European perspective, this ‘response’ has only been political, with Russia closing the flows to different European clients, including Germany, sending shockwaves all across the world and contributing to the disruption of several regional energy markets.

At the same time, the Sino-Russian gas trade has been invigorated. In a push to reduce the reliance on the US dollar, Beijing and Moscow agreed to switch from dollar to ruble and yuan payments for gas. Furthermore, Gazprom has repeatedly bragged about new daily record volumes of Russian gas delivered to China through the Power of Siberia pipeline. For Beijing, Russian pipeline gas is rather more convenient compared to spot purchases. Interestingly, if China were to source all Russian gas imports from alternative exporters of LNG, around 15 bcm in 2022, this would have further aggravated the EU’s run to refill its gas storage, increasing the costs of securing gas stocks before the winter season.

Since December, the last leg of the Chinese section of the Power of Siberia pipeline, from Tai’an to Taixing, has been completed by PipeChina, enabling Russian gas to flow to the financial and industrial hub of Shanghai. At the same time, Gazprom is accelerating the development of the Far Eastern Route, with a view to increasing gas shipments from Russia’s Easternmost regions to the Northeast of China by 2025. Meanwhile, discussions about the mammoth Power of Siberia 2 (PoS-2) project, connecting Western Siberian gas fields to Beijing, continue. With 50 billion cubic meters a year (bcm/y) of capacity, this pipeline would deliver Russian gas developed in the Yamal basin to North China via Mongolia.

According to Russian Deputy Prime Minister Novak, Russia’s goal is to increase exports to China up to 100 bcm/y in the near future. In this regard, the consistent problems displayed by Central Asian states in supplying steady flows of natural gas to China throughout this winter might become an asset for Moscow in the bilateral negotiations. The completion of the PoS-2 would allow Russia to supply China with around two-thirds of Russian gas exports to Europe as they stood in 2021. But so far, no final contract for the construction of the project has been signed and the pipeline would take at least five years to be realized. For sure, such an agreement would be supportive of the “all time high” narrative, meaning that both presidents would need to be present at the signing ceremony. The likely visit of Xi to Russia in spring could shed some light about the status of the allegedly advanced negotiations.

Oil, Embargoes, and Fluid scenarios

In the context of the global oil market, the Sino-Russian energy partnership is also in the spotlight. China is on the course to receive increasing amounts of Russian oil through both the ESPO pipeline and Russia’s Far East port of Kozmino, which also accepts occasional cargo of Urals blend. The price of Russia’s main oil benchmark has fallen to its lowest since November 2020, implying that the government might be forced to reconsider its estimates for the 2023 budget. In response, Moscow has created a shadow fleet of dozens of vessels able to ship Russian oil outside the control of the West and its allies in order to support its exports. Still, this has not yet reached the size which would enable Urals crude oil and other products to freely reach destination markets. Therefore, it is likely that Russian companies could be forced to shut production and reduce refinery runs, as they fret to sell the last uncapped diesel barrel to Europe at lowball prices.

Non-compliant with the cap, Chinese state-owned tankers are reportedly shipping Urals to China. Today, large-capacity vessels travel up to the Mediterranean and Baltic ports, becoming the hub for ship-to-ship transfers, before heading to Asia. Chinese tankers are also reaching Indian buyers, the latter being the ‘greediest’ in terms of sanctioned Russian oil. Together, China and India now account for over 90 percent of the entire Russian crude exports and once well-established, these emerging logistical schemes could ensure more profitable margins to Russian producers than those they would reap without Chinese support.

At the same time, keeping Urals afloat has always been a primary target of the US, with the Biden administration trying to avoid a collapse of Russian exports and a new global inflationary spiral, whilst also banning all imports of Russian oil. Since Beijing has increased the export quota by almost 50 percent, Russian diesel, and other products could end up in Chinese refineries, and then be re-exported at profits to Europe, balancing market shortages. Awash with Russian oil, private Indian refineries have also ramped up exports and, as it seems, Washington has been their most eager buyer, confirming that even among the Western coalition, different perspectives exist about hampering Russian energy exports.

For now, the re-jigging of global oil flows does not seem to have weakened the Sino-Russian partnership and, as long as the Russian oil is sold below the price cap threshold, the business appears to be legitimate, even to Western observers.

Future of the Partnership

Against the backdrop of a return of energy geopolitics to the forefront of international affairs, where energy embodies a primary instrument in great power competition, a series of tests awaits Beijing and Moscow.

If China’s behavior and economic rebound will influence the maximum threshold of global oil and gas demand, likely supporting higher global prices, Russia’s initiatives could intensify the lingering tensions between producers and consumers. Moscow would be more than happy to exacerbate and exploit the fragility of the markets, filling any empty space left by the divergent strategies adopted by developed economies and the Global South to face the current situation, with the latter refocusing on dirty fossil fuels for the sake of energy security. Yet, Beijing would also see its space for maneuver expanding within a multipolar conceptualization of the energy transition. China could attain much by supporting developing economies to shield them from the instability of global energy markets, offering bilateral financial and technological assistance, in contrast with the liberal model of international climate diplomacy and green finance advocated by the USA and EU at COP27.

There are few doubts that, in the future, China and Russia will continue to look at energy cooperation as an anchor of their bilateral relationship. As they do so, the reality of their trade in energy commodities becomes a mainstay of global energy markets amid the great reshuffling of the energy order. Presumably, this will be welcomed as good news by shaky energy markets. Paradoxically, the same works for those actors most affected by the current energy crisis, such as the European Union. However, political instability and market volatility might become an excuse for profiteering over each other’s vulnerabilities. Even if stopping short of compromising the overall relationship. In the end, are not we all living in the age of the “all-time-high” Sino-Russian strategic partnership?

Written by

Francesco Sassi

Francesco Sassi (Ph.D.) is Research Fellow in energy geopolitics and markets at RIE, Ricerche Industriali ed Energetiche, and he collaborates, on an ongoing basis, with the Energy Security Focus of the Italian Parliament and the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation. His research focuses on the policies and strategies in the fields of energy security and diplomacy, the political and economic effects of the globalization of the natural gas market, and the relationship and power dynamics between governments, state-owned energy companies, and markets.