This year marks half a century since the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Greece. But while until recently, Beijing and Athens heralded close ties, new challenges increasingly cloud the future prospects of the relationship.

A Low-Profile Anniversary

Although the 50th anniversary of bilateral ties might have been expected to be celebrated with much fanfare, it has not been given much attention in either China or Greece. To mark the occasion, on June 5, Chinese President Xi Jinping exchanged congratulatory messages with Greek President Katerina Sakellaropoulou, and Prime Minister Li Keqiang did the same with Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, stressing the achievements of the bilateral partnership and the need to expand cooperation further. Similarly, to celebrate the anniversary, in late May, the Athens-based Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation hosted an event entitled ‘China and Greece: From Ancient Civilizations to Modern Partnership’, which was organized in cooperation with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and the Chinese Embassy in Greece.

Beyond that, the anniversary was not accompanied by the usual high-level visits between political leaders that have been a key feature of China-Greece relations until recently. Nor were there any pledges for new investments or tangible plans for furthering cooperation.

Perhaps, the new wave of stringent restrictions in China as a response to the pandemic has prevented such visits or the organization of other events. But virtual meetings or phone calls are regularly held as an alternative in such circumstances, so this would not explain the rather low profile of the anniversary.

In reality, although Beijing and Athens continue to stress the importance of their partnership, a series of recent developments indicate that, after reaching a high point between 2016 and 2019, Sino-Greek relations are now entering a period of ‘normalization’ characterized by adjustments and constraints mainly as a consequence of a reconfigured geopolitical environment.

Looking Back

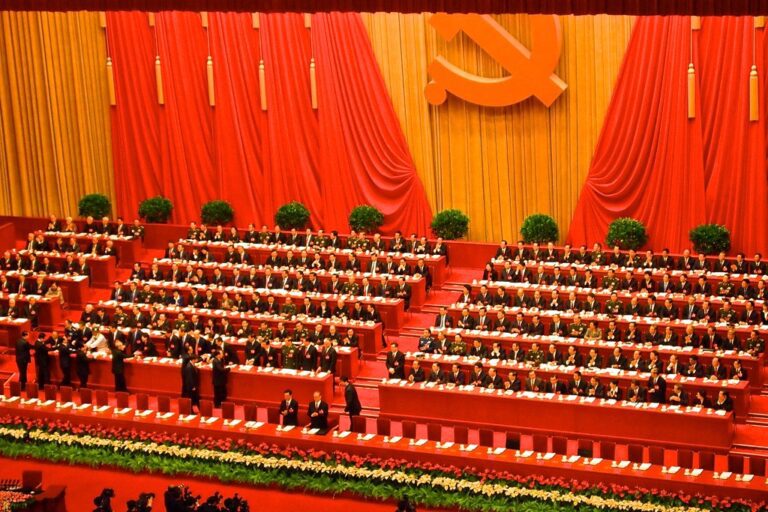

Relations between China and Greece have made significant progress over the past 15 years, so it is necessary to briefly say something about their historical context. The first steps towards closer ties were made in 2006 when the two countries decided to elevate ties to a ‘Comprehensive Strategic Partnership’. A breakthrough was achieved shortly after, when COSCO, China’s largest state-owned shipping company, won a 35-year concession to operate an important part of the Piraeus port in 2008. Crucially, this upgrade owed much to the agency exerted by Greek shipowners and Captain Wei Jiafu, who was then the President and CEO of COSCO.

However, it is not surprising that the Eurozone crisis had a profound impact on China-Greece relations. By 2016, the SYRIZA-led coalition government headed by Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras was politically and economically vulnerable, under EU pressure to privatize the public sector, and bereft of much-needed economic sources to fulfill the requirements of Greece’s third bailout.

Meanwhile, Beijing was interested in taking advantage of the opportunities offered by Athens, especially given that the strategic significance of the Piraeus port had increased as a result of Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Therefore, the stage was set for the 2016 Port Piraeus deal, when COSCO announced that it had acquired a 51 percent stake in the Piraeus Port Authority (OLP). Since then, China’s involvement in the port has been hailed as a success, manifested in the remarkable increase in the port’s traffic. China has also become one of Greece’s most important trading partners with a share of approximately 7.7 percent of total imports, ranking behind Germany and Italy.

From Economic to Political Cooperation

One of the most notable aspects of China-Greece relations from 2016 to 2019 was that they were not limited to economic cooperation, but also expanded to involve the deepening of political ties. During this period, there were at least two occasions when Greece’s foreign policy seemed to diverge greatly from the EU’s position toward China which attracted much attention.

The first was in July 2016, when Athens objected to a statement by the EU regarding the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration over China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea. Following three days of talks, the EU statement did not contain a reference to Beijing. Similarly, in June 2017, Greece blocked an EU statement at the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) that aimed to condemn human rights abuses in China, the first time such an EU statement was not issued at the UN’s human rights body. In both cases, Greece’s position was seen to be derived from its closer ties with China.

Another important aspect of this period was Greece’s participation in China-led multilateral initiatives. Typifying this was Greece’s joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as well as the cooperation format between China and Central and Eastern European Countries, or the “17+1,” in April 2019, which raised eyebrows in Brussels. The strengthening of political ties was also evident in the frequency of high-level mutual visits that continued after the election of the center-right government under Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis, epitomized by Xi’s unprecedented three-day visit to Greece in November 2019.

The transformation of Sino-Greek relations between 2016 and 2019 was so remarkable that Greece emerged as a quintessential example of how China successfully uses investments in strategic sectors to translate its economic power into political influence over smaller EU member states to the detriment of Brussels. This prevailing narrative gave rise to the meme of Beijing exploiting Athens as yet another ‘Trojan Horse’ to achieve political gains, challenging the norms and unity of the EU.

Gradual Adjustment Since 2020

Although China was able to attain some political gains at the symbolic level in Greece, concerns about Beijing using its economic leverage over the small European country as a way to exercise greater political influence within the EU look increasingly overblown. To be sure, there is a degree of continuity in China-Greece relations, as both Beijing and Athens continue to stress the significance of their partnership. After all, for the Chinese leadership, the Piraeus port serves as China’s gateway to Europe and remains a flagship project under the BRI associated with the so-called ‘China-Europe Land-Sea Express Line’.

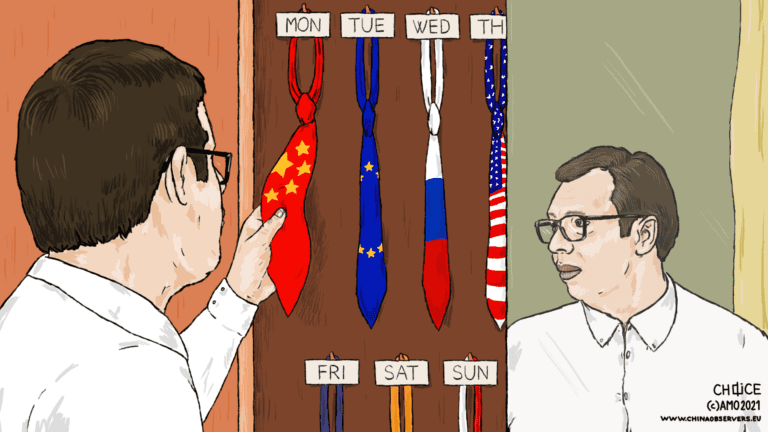

But there is also growing awareness both in Beijing and Athens that there are important constraints on the nature of the bilateral relationship. First, Sino-Greek relations are increasingly mediated by a complex and reconfigured geopolitical environment. In recent years, Greece has been keen to reinforce its ties with key allies, such as the United States and France, mainly as a result of Turkey’s aggression in the Eastern Mediterranean, where China is not able or willing to play the role of a security provider.

Second, given the intensifying Sino–US great power rivalry and the deterioration of EU-China relations, Greece, as an EU and NATO member, is under pressure to balance its strategic and economic priorities, which already has effects on its relations with China.

Third, as the state of the Greek economy has improved, leading to investments from other countries, such as the United States, the salience of Beijing as a source of much-needed capital has decreased.

Finally, even China’s involvement in the Piraeus port, the most successful Chinese investment in Greece, has been met with local and bureaucratic resistance, which serves to illustrate the role of domestic politics and the complexity of factors shaping China-Greece relations.

Consequently, Greece has attempted to adjust its China policy. For example, Athens decided not to host the gathering of the China-CEE cooperation platform in 2022. Since 2020, Greece has also not repeated any of the previous ‘unity-breaking’ moves that challenged the China policy of the EU. Economically, apart from the Piraeus port and another major Chinese investment in Greece’s electricity grid operator in 2016, Chinese SOEs have been eased out of public tenders. Likewise, in 2020, the largest Greek mobile operator chose Swedish Ericsson over Huawei for its 5G network.

In this context, it becomes easy to dismiss the significant development that has occurred in China-Greece relations over the last decade and the potential opportunities for further cooperation, even under current strategic dynamics. Indeed, it is only through the prism of the high expectations raised from 2016 to 2019 that the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations may look a less happy one. In any case, whether Beijing and Athens can effectively manage their relations in a rapidly changing environment, especially amid much uncertainty and strategic realignments, remains to be seen.

The article builds on the recent publication by the author on China-Greece relations, published open access in the Journal of Contemporary China.

Written by

Dimitrios Stroikos

DStroikosDimitrios Stroikos is an LSE Fellow, Department of International Relations, and Head of the LSE IDEAS Space Policy project, London School of Economics and Political Science. He is the co-editor of a forthcoming book on China-Europe relations (Oxford University Press).