The threat posed by China to NATO countries is growing due to China’s cooperation with Russia, the two powers’ ambition to remodel the international order, and the risk of destabilization in the Indo-Pacific.

NATO’s New Focus

The recently concluded NATO summit in Madrid delivered a new Strategic Concept defining the most important security challenges and outlining the future tasks for the Alliance. The document includes –for the first time in NATO history – a significant passage describing the clear and present dangers originating from China.

China is mentioned in the Concept not only as a country that directly threatens the political and economic stability of NATO member states but also – which is more significant – through the lens of its cooperation with Russia. The Concept focuses on non-military security challenges coming from China, e.g. hybrid and cyber operations, economic coercion, disinformation, cybersecurity, control of key technologies, and critical infrastructure – all of which are employed by Beijing to increase China’s global footprint and project power. These activities have the ability to undermine the development of defense capabilities by the allies, especially those burdened with providing military equipment to Ukraine and struggling with the economic consequences of the war.

NATO’s new Strategic Concept came as a logical consequence of NATO’s previous activities in the Indo-Pacific, perceived by China as a threat to its core interests and strategic goals. These developments were originally based on the changing security situation in the region facing the impact of China’s long-term ambitions to become a regional superpower and its efforts to develop a basis for controlling the region militarily, politically, and economically.

Along with the Chinese militarization of the South China Sea, military reforms, growing military budget, and intensifying provocations towards Taiwan, ties between NATO and regional allies including Australia, Japan, and South Korea, have been tightened. China’s political support for Russia after the invasion of Ukraine and both countries’ common drive to undermine the rule-based international order have accelerated these processes. NATO is no longer only focused on its Eastern Flank and Russian threat but, despite the geographical boundaries, tries to engage more in the Indo-Pacific with a clear understanding of combined security threats.

In part, NATO’s growing presence in the Indo-Pacific is also a reflection of a dynamic debate in the US about the limitations of American global engagement and its policy priorities. Recent decisions by the Biden administration (Zawahiri’s assassination in Afghanistan, sets of military packages for Ukraine, and Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan) show its ability to equally engage on different fronts. At the same time, political debate on the US necessity to triage its geopolitical priorities is vivid and becoming more important during the campaign before the upcoming midterm elections.

Russia and China‘s shared justification of changing borders through the use of force raised the possibility of such a scenario occurring in the Indo-Pacific as well. NATO and its regional partners in Asia have become aware that failure to stop Russian and Chinese plans in the coming years might result in a catastrophic reorganization of international order leading to permanent instability and a high probability of new conflicts.

China’s Boilerplate Response

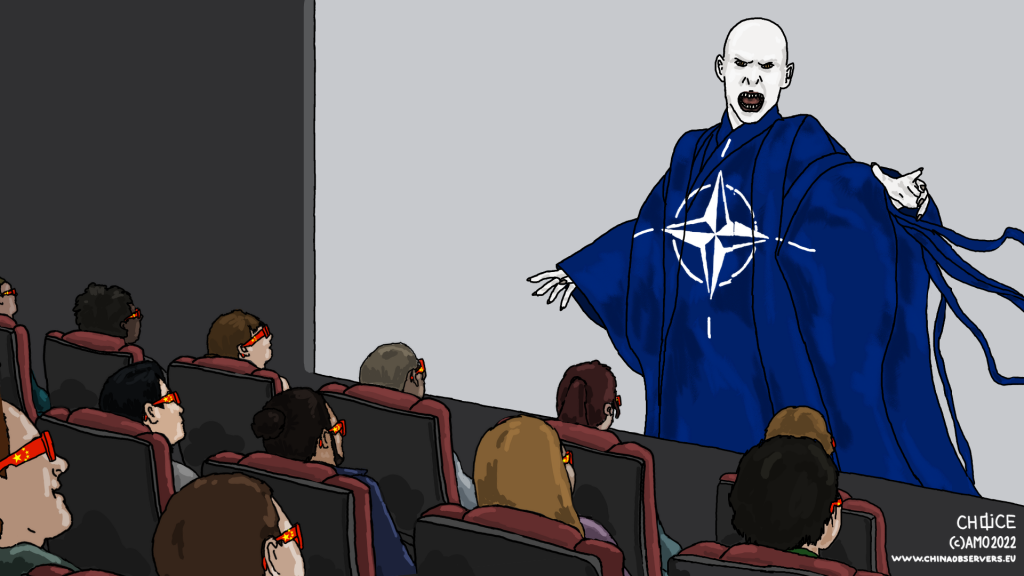

What has China’s response been to NATO’s growing focus on China’s geopolitical neighborhood? The Alliance has always been painted as an American political tool in Chinese propaganda, even though the Chinese viewed it as disoriented after the end of the Cold War and desperately searching for new goals and policy objectives since the 90s. In China’s optics, it was the US influence that made NATO more interested in Indo-Pacific in the recent years, parallel to the growing US-China rivalry.

Before the invasion of Ukraine, NATO itself was not a particularly prominent target of Chinese propaganda but it still featured in the Chinese debate. Chinese authorities tried to amplify the existing differences in the Alliance, e.g. by repeating the “brain dead” assessment of President Emmanuel Macron from 2019. In some respect, the attitude towards NATO shared some similarities with China’s policy towards the EU – to prevent the development of anti-Chinese policies and curtail the US influence within the Alliance. China tried to limit NATO’s engagement in the Indo-Pacific in the short term, feeding the disagreements within the Alliance with the hope of impairing its decision-making efficiency.

NATO’s reaction to the Russian invasion of Ukraine proved these expectations were wrong. But instead of reducing its rhetoric and underlining the similarities with the West, China focused on strengthening the differences, amplifying the narrative on the dangers of “creating an Asian NATO” and painting the US’ involvement as the main cause of regional destabilization, similar to Europe.

Chinese repeated the accusations after the publication of NATO’s Strategic Concept. Both Russian and Chinese propaganda constantly blame NATO’s enlargement in the 90s as a legitimate threat to Russian security as a root cause of the Russian invasion of its neighbor. In effect, China also provides justification for its actions by pointing at the US activities in the Indo-Pacific as threatening its core interests and security. Just as Russia declines Ukraine’s right to exist, China has reaffirmed its long-term claims on Taiwan as “part of China” in need of “reunification.” However, this is mainly propaganda – China’s decisions on economic and military repercussions against Taiwan did not require Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, just like Russia did not invade Ukraine because of “denazification”.

China as a Paper Tiger?

Chinese reaction to Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan can serve as a clear example of China’s considerations in its response to the US (but also NATO): strong rhetoric coupled with a deep understanding of the limitations of operational capabilities in the Taiwan Strait and Indo-Pacific in general. Military drills initiated were larger and more sophisticated than before but focused mostly north and south of the “centreline” in Taiwan Strait, not the middle. China also restrained from using instruments which could lead to more escalation, such as flying the planes over the island or violating the territorial waters within 12 nautical miles of Taiwan.

People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been undergoing a long-term reform accelerated by Xi Jinping, focused not only on the development of high-tech and naval equipment but also on structural and operational changes in order to be able to win a regional, modern conflict like the invasion of Taiwan. In June this year, Xi Jinping signed new regulations which give PLA the possibility to conduct “special military operation” in “non-war” activities abroad. Xi also inaugurated the Global Security Initiative – mainly a propaganda instrument to present Xi as a global leader – featuring a special interpretation of countries’ “legitimate rights” to use force if they consider their security interests endangered. However, these reforms and political initiatives so far lack substantial results and remain far from having a real effect on the PLA’s warfighting capabilities.

At the same time, the PLA’s operational skills have not been tested in real conflict for decades. The PLA has focused its training on military exchanges with Russians, which casts some doubt on the military’s actual fighting capabilities. The main results of military reform under Xi have been nominations to higher ranks for Xi’s protégées which allows him to control the military, but also to ‘pay his debt’ of loyalty to the military comrades who supported him within the Party. Such a network of relations is helpful to keep the PLA focused on internal stability, especially with an eye on this year’s 20th Party Congress, looming generational change in the leadership and the growing social and economic problems keeping Chinese leaders busy in the coming months.

Global Repercussions

Even though the international situation has changed dramatically after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, China struggled to adapt to the new reality. Many of Beijing’s political objectives failed with NATO engaging more in the Indo-Pacific and the West emerging more united than before. The Chinese leadership was unable to react due to internal constraints and inadequate access to information, prioritizing instead the maintenance of ideological unity and sticking to its revisionist approach. Beijing bolstered the narrative on “NATO as the main destabilizer” and engaged more in cooperation with Russia focused on “changing the international order.”

For many years Xi Jinping and the Chinese leadership based their legitimacy on China’s advantages against the West and the need for “rejuvenation” of the Chinese nation to the detriment of the US and its partners. Despite a sudden change in the international situation, it was impossible for Xi to suddenly abandon the previous source. Ultimately, Chinese policies can result in a direct military engagement of a NATO member in regional escalation, especially in a Taiwan contingency. The threat coming from China described in the NATO Strategic Concept could therefore seriously undermine NATO member states’ ability to respond to such a crisis and is impossible for the Alliance to ignore.

Written by

Marcin Przychodniak

Molos123Marcin Przychodniak is an Analyst at Asia-Pacific program at the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM), focusing on Chinese politics and a former diplomat in Beijing.