China is Playing an Increasingly Active Role in Serbia, Part of Its Expansion in Central and Eastern Europe.

Despite a renewed interest on Beijing’s part, China’s relationship with the European Union encountered a number of setbacks in 2018, the latest being the tightening of foreign direct investments by the European Commission. In December, Europe’s strongest economy, Germany, made it even harder byestablishing new rules against foreign acquisitions of German companies in technology.

In the Balkans, just outside the EU, China is enjoying a different experience. A non-EU member, Serbia claims to have become one of China’s best friends in Europe. Beijing has engaged in a number of massive projects in the Balkans, although the most high-profile one, the Belgrade-Budapest high-speed railway, has failed to materialize so far.

China’s relationship with Yugoslavia had ups and downs from 1949 on. Originally, Marshal Josip Broz Tito, leader of Communist Yugoslavia, of which Serbia was a constituent republic, wanted to engage with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) but was rebuffed by Mao Zedong because of Tito’s split with Stalin. Although Yugoslavia started recognizing the PRC diplomatically in 1949, Tito waited until 1977 to visit Beijing for the first time.

As China’s relations with Enver Hoxha’s Albania started to deteriorate, Yugoslavia — then Serbia — became the partner of choice, giving China an entry point into Southeastern Europe. The relationship continued to be smooth through the 1980s (Tito died in 1980) and 1990s, well into Slobodan Milosevic’s presidency. Following the civil war and the breakup of Yugoslavia, Milosevic visited China as the Serbian president in 1997 and was able to claim China’s diplomatic support two years after the Dayton peace agreement. This breakthrough was seen as important in Sino-Serbian relations. Beijing was keen to support Belgrade’s view on Kosovo, reflecting its own situation vis-a-vis Taiwan, and even Hong Kong, under the principle. “Just as Serbia supports the one-China policy, China supports Serbia as its best and most stable friend in southeastern Europe,” Serbian Deputy Prime Minister Bozidar Delic said in Beijing in 2009. Serbia would later receive Beijing’s support against EU pressure to recognize Kosovo’s independence.

Another serious event brought China and Serbia even closer together: On May 7, 1999, five U.S. Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) guided bombs, part of a NATO operation, hit the PRC embassy in Belgrade, killing three Chinese reporters and leading to a reaction of outrage by Beijing. Although the U.S. administration stated that this strike was accidental, there have been continuous doubts in China, with many feeling that it was an intentional act on the part of the United States.

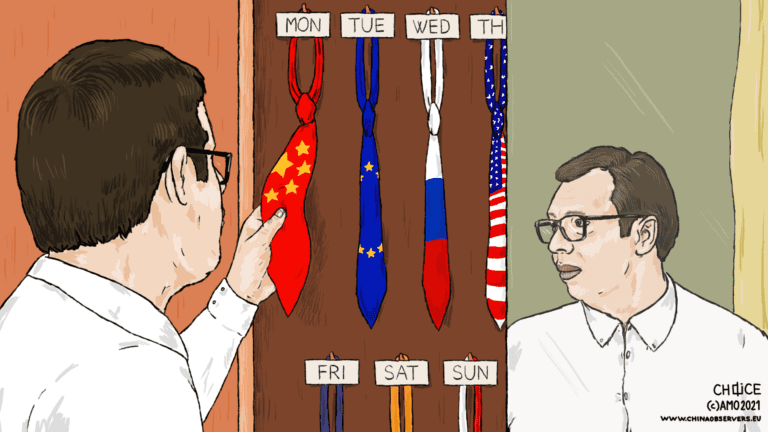

Serbia’s drive to strengthen political and diplomatic relationship with China has been greatly driven by the Kosovo issue, but also by Serbian perceptions of a shift in the balance of power. The 2008 financial crisis instilled a sense among Serbian leadership that the West is vulnerable and that China is rising. The notion of rising China is also acknowledged by the incumbent President Aleksandar Vucic: “Thirty years ago you had one, absolutely dominant military, political, and economic power [the U.S.] …With its economic, but also with its military and political power [the] People’s Republic of China dramatically catches up.”

The closeness between the two regimes appeared striking during the 10th anniversary celebration of the ruling Progressive Party of Serbia (SNS), where the Chinese Ambassador to Serbia Li Manchang was the guest of honor. More recently, Serbian leadership also consulted with the Chinese ambassador on the issue of Kosovo, which is another role that the incumbent Serbian government traditionally reserved for the Russian Embassy. This implies the growing diplomatic influence of China in Belgrade.

The Level of Chinese Involvement Today

The Serbian government, which has been knocking on the EU’s door for some years without much success, is now turning to China as an economic partner. “It would not be immodest or wrong to call Serbia China’s main partner in Europe,” stated Minister for Construction Zorana Mihajlovic. As it tries to identify opportunities in this formerly troubled region, Beijing is more than willing to engage economically with Belgrade, which is not averse to “state-led decisions, with the politicization of investment, subsidy and contract decisions, rejecting the EU’s model of open and transparent bidding procedures.” Since 2017, the two countries have abolished visa requirements and stepped up political cooperation.

Trade between China and Serbia tripled between 2005 and 2016, to $1.6 billion, but it is a very unbalanced relationship: China exports $1 billion in goods, whereas Serbia exports $1 million of goods to China. Investments are rising because the Belgrade government is able to move quickly as a non-EU member.

In 2016, while President Xi Jinping visited Belgrade, Vucic (then the prime minister) insisted that China would bring more jobs, improve living standards, and lift the country’s economic growth. That same year, China’s state-owned HBIS Group took over Smederevo’s steel mill for 46 million euros ($55 million). The steel mill generates 5,200 jobs in Smederevo, a city of 100,000 that has depended on the mill for decades. Its previous owner, U.S. Steel, had sold the mill back to the Serbian government in 2012 for a symbolic $1.

Chinese companies also are actively building infrastructures — for example, the Zemun-Borca Bridge, built by the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC), using Chinese materials for 50 percent of the construction.

A local businessman who served as a subcontractor for the project explained in an interview, “As Serbia does not have the funds for such [a] project, having a Chinese company in the lead with financial backing from Exim Bank with local subcontractors was part of the deal.” There is no procurement process; the government decides on the arrangements. It is clear that the “Chinese way,” which has been in full swing in Africa or South Asia, for example, is more suitable to less regulated, pluralistic countries. Serbia is one of them. The CRBC is also involved in building the Surcin-Obrenovac section of highway E793, which leads to a “China-Serbia industrial park.” During the summer of 2018, it was also announced that a Chinese company, Shandong Linglong, would be investing $1 billion investment in a new tire company from April 2019 in Serbia’s Zrenjanin Free Trade Zone, with a completion date of March 2025. A deal was also reached about China supplying military drones to Serbia, which will be producing some of the drone systems in the future.

Other Balkan countries have also benefited from Beijing’s “generosity”: Montenegro received a $500 million loan from the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim) for its portion of the highway, and Northern Macedonia was offered a $580 million loan in 2013 to help build its own highway.

Meanwhile, China Pacific Construction Group, one of China’s largest construction companies, has begun building an expressway between Montenegro and Albania. In January 2018, Vucic — who became Serbia’s president in 2017 — called on China to invest in RTB Bor, a copper miner and smelter. This was finalized in August 2018 when Chinese company Zijin Mining took a 63 percent stake in RTB Bor.

It is hard not to notice China’s physical presence in Belgrade. First, there are more Chinese nationals in the Serbian capital than in most European cities. Many are tourists, businessmen, or employees of major Chinese companies, such as Huawei, a semi-private Chinese company with a very visible presence in Belgrade (as in other countries, it has been supplying equipment to government entities), or the Bank of China, which has opened a representative office there. China North Industries Group Corporation Limited (Norinco), a company directly under the supervision of the People’s Liberation Army, is also represented in the city but operates mainly in Albania, Northern Macedonia, and Montenegro. The no-visa policy for Chinese visitors has been a major factor in encouraging their increased presence.

China has not yet bought up the Balkans. In fact, the EU’s structural funds in the form of grants are larger and cheaper than Chinese loans, but politics — and poor governance on the part of some local politicians — play a major role in favoring China. The Brussels grants come with strings, rules often unwelcome by the political elites of the Balkans. The EU bureaucracy can be slow — a problem when governments try to move fast to gain electoral capital — hence the success of the Chinese model “aligned with local political cycles.” Ironically, the six Balkan countries still are hoping to join the EU in the not-too-distant future.

In addition to trade, recent statements by Vucic imply a growing political relationship between China and Serbia. In 2019, Xi is expected to pay his second visit to Serbia as China’s top leader. It will be a statement of China’s strategic interest for southeast Europe, where it has been building a strong presence. Serbia, Montenegro, Northern Macedonia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Albania (all former socialist countries) are all members of the 16+1 forum, China’s main platform in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE). With an important presence in Greece, China now aims to open a transport route through Central and Southeastern Europe, and south all the way to the Mediterranean Sea. To the north, in Central, Eastern, and Southeast Europe. The Balkans have become a top priority of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, on which 16+1 meetings now center, even though most projects over the past few years have been the result of strong bilateral links — for example, between China and Serbia. “China sees the Balkan countries as potential EU members, which could be of utmost importance,” says Sonja Licht, who chairs the Belgrade Fund for Political Excellence.

Unlike in Central Europe, the role of Russia in the Balkans is also a factor. Moscow has been a strong supporter of Serbian policy, especially vis-à-vis Kosovo. Moscow’s main purpose is to keep Serbia away from NATO (unlike Montenegro, a small nation of 600,000 people, which joined NATO in 2017), and possibly the EU. Russia also wants to remain the largest supplier of energy to Serbia. The Russian leadership has remained highly influential with successive Serbian governments. In this region, a light China-Russia collaboration is not impossible, as suggested by the creation of a rather opaque “council of economic cooperation with Russia and China” chaired by former President Tomislav Nikolic, an ally whom Vucic persuaded not to run for president in 2017.

As in many countries, China has been inviting numerous Serbian journalists, especially to BRI-related events. “Everything to do with China is treated and covered positively in government circles and in the Serbian media,” said Jelena Milić of the Center for Euro-Atlantic Studies in Belgrade.

There are active Chinese language schools, including at the two Confucius Institutes in Belgrade and Novi Sad University. A new massive eight-story Chinese cultural center is under construction on the site of the bombed Chinese embassy. Despite the increased presence of Chinese nationals in Serbia, China is still seen as a “remote” country, with little cultural appeal to young Serbians, who are emigrating to Western countries in large numbers, driven away by the lack of job opportunities at home. Perhaps out of frustration over past specific Western policies, many Serbians have become somewhat anti-Western, favoring closer links with powers like Russia and China. Although it is hard to detail China’s influence on Serbian political elites, there is undoubtedly a shift in a society still recovering from its long period of war.

China’s growing opportunistic interest in Serbia has been described as a form of “neocolonization” by a local observer. Vucic says otherwise: “This friendship [between China and Serbia] has been demonstrated, proven, and confirmed in the most difficult moments through Serbian history, and we are grateful to its leadership, headed by President Xi Jinping, for the support it provides to Serbia, our people and citizens.”

Serbia’s special situation as a European country outside of the EU — with an uncertain path toward membership — has made it a special target for outside major powers. Russia is one of the most obvious ones, but China is increasingly active.

As analyst Milos Popovic wrote in his report for the Belgrade Center for Security Policy (BCSP), Serbian foreign policy and security policy remains unsure, especially when it comes to the concept of “military neutrality” and the scope of Serbia’s ties to Russia.

In a survey conducted for BCSP in 2016-2017, Popovic asked respondents what they thought of the major powers and their influence on Serbia. China ranked second (after Germany) among “credible investors,” ahead of the United States, Russia, and the EU as a whole.

The general public does not seem to have strong views on the domestic situation in China; it sees China in the Serbian context. International media reports are sparse, and Serbians seem focused on the recovery of their own country rather than geopolitics. Most perceive China as a friendly country that has come to invest in the (slowly recovering) Serbian economy.

There is obviously an EU concern — including in Berlin — that China will use the Balkans as a new entry point into the European market and try to promote its own political model in countries with weaker governance as opposed to the EU model of liberal democracy. But as the EU is facing increased divisions over a large number of issues, it looks unrealistic to envisage the Balkans joining the Union anytime soon – leaving China and others to occupy a somewhat empty space.

This article was originally published at The Diplomat.

Written by

Vuk Vuksanovic

v_vuksanovicVuk Vuksanovic is a PhD Researcher in international relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), an Associate of LSE IDEAS, LSE’s foreign policy think tank, and a Researcher at the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy (BCSP).

Philippe Le Corre

Philippe Le Corre is a nonresident Senior Fellow in the Europe and Asia Programs at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Le Corre is also a Senior Fellow with the Harvard Kennedy School’s Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, an Affiliate with the Program on Europe and the Transatlantic Relationship at Harvard's Belfer Center and an Associate in research with Harvard’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies.