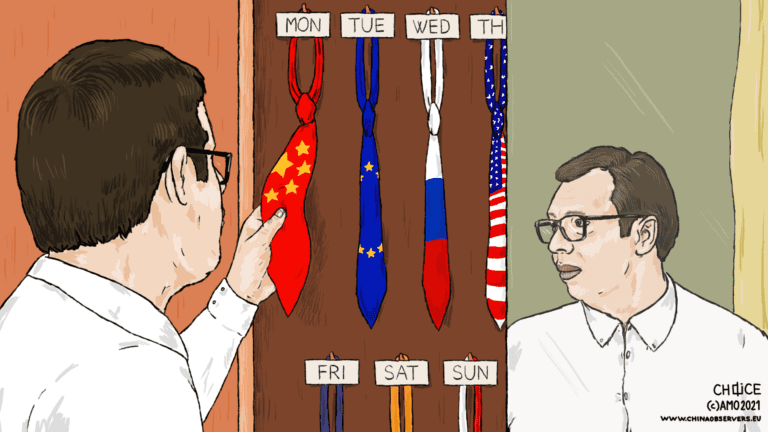

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has redrawn the geopolitical map, intensifying the bifurcation of the global system between Washington and Beijing. For Kyiv, this has sharpened the dilemma of how to balance its foreign policy – that is, maintain ties with China, its largest individual trading partner, while deepening integration with the EU and aligning with US security priorities. Nowhere is this balancing act more evident than in trade. Yet Ukraine’s recently launched export strategy remains largely Euro-centric, with only limited reference to China and other non-Western markets.

From Recognition to Wartime

China recognized Ukraine’s independence on December 27, 1991, establishing formal diplomatic relations in January 1992. The 1990s and early 2000s were marked by cautious yet steady engagement: Ukraine sought to diversify its foreign policy beyond Russia, while China aimed to expand its influence in the post-Soviet space and secure access to Ukraine’s industrial and agricultural resources, as well as its strategic geography.

Ukraine played a notable role in China’s technological modernization during this period, particularly in aerospace, defense, and heavy industry. A defining moment came in 1998, when Ukraine sold the unfinished Varyag aircraft carrier hull to a private Chinese buyer. It became the Liaoning, China’s first aircraft carrier and the cornerstone of its naval modernization program.

By the early 2000s, bilateral trade surpassed $500 million annually, maintaining a steady upward trend ever since, driven predominantly by Ukrainian metallurgy and aerospace exports. However, political instability and the slow pace of market reforms constrained Chinese investment, which has never exceeded 1 percent of Ukraine’s total FDI. The 2004-2005 Orange Revolution cooled political ties as President Viktor Yushchenko’s pro-Western orientation distanced Kyiv from Beijing. High-level visits halted, though trade volumes continued to grow – reflecting the resilience of economic interdependence amid limited political alignment.

The presidency of Viktor Yanukovych, widely regarded as pro-Russian, marked a high point in Sino-Ukrainian engagement. The 2011 strategic partnership agreement and the 2013 Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation were accompanied by large-scale pledges of Chinese investment in infrastructure and energy. Both the 1994 Joint Declaration and the 2013 Treaty formed part of the legal framework underpinning Ukraine’s security assurances. In 1994, China praised Ukraine’s nuclear disarmament, urging other nuclear powers to offer similar guarantees. The 2013 Treaty reaffirmed that China “under no circumstances” would use (or threaten to use) nuclear weapons against Ukraine and pledged mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity. These commitments, however, remained largely rhetorical, falling short of translating into concrete security guarantees. In 2024, Kyiv sought to remind China of these assurances in its UN appeal, calling for special security guarantees from nuclear states, including China – so far without tangible results.

Ambiguity and Economic Continuity

While China’s political stance on the Russo-Ukrainian war has leaned toward the former, its economic engagement with the latter remains substantial. Since the outbreak of the war in 2014, China maintained an officially neutral position, refusing to recognize Crimea or the occupied Donbas as Russian territories. Top-level political engagement stagnated, with the strategic partnership existing mostly on paper. Xi Jinping never visited Kyiv, and neither President Petro Poroshenko nor Volodymyr Zelenskyi were invited to Beijing.

It was not until Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022 that China’s position changed. Beijing shifted from formal neutrality to what has been described as “pro-Russian restraint” or “strategic ambiguity.” It has refrained from condemning Moscow, while deepening strategic coordination between the two powers and echoing narratives blaming NATO expansion for the conflict. At the same time, it has avoided recognizing Russian claims over Ukrainian territory and supplying lethal weaponry, thereby preserving a narrow channel for dialogue with Kyiv.

Economically, trade has persisted, with exports driven largely by Ukrainian grain supplies under the now-suspended Black Sea Grain Initiative. China was the single largest beneficiary, importing over eight million tons. The damage to Chinese-owned assets in Ukraine, such as COFCO’s grain facility, highlighted the risks for Chinese investors, yet Beijing remained publicly silent, neither commenting on the incident nor assuming a formal mediation or guarantor role. In 2024, bilateral trade reached $16.8 billion, dominated by Chinese imports, with Ukrainian exports totaling only $2.4 billion. The first half of 2025 confirmed this dynamic: exports to China fell by 47 percent, whereas imports rose by 26.8 percent.

Pragmatism under Pressure

Sino-Ukrainian relations illustrate how smaller states pursue economic pragmatism amid great-power rivalry. Despite Beijing’s strategic tilt toward Moscow, trade – particularly imports – remains resilient. Still, Ukraine’s 2025 export strategy is distinctly Euro-centric, assigning China only a limited role. This contrasts sharply with consultations for the 2030 export strategy, in which 40 percent of respondents identified China as a priority market for the agrarian sector – behind the EU, the Middle East, and Africa, but ahead of India, Korea, Japan, and others.

In 2025, under President Trump’s administration, Kyiv signed a minerals agreement that consolidated US influence over Ukraine’s CRM sector. Ukraine holds significant reserves of titanium, lithium, graphite, and rare earth elements – resources vital for high-tech manufacturing, defense, and the green transition. In China, the deal was viewed as part of Washington’s broader efforts to limit China’s access to strategic resources through restrictive “poison clauses” embedded in trade and investment agreements that either implicitly or explicitly bar partner countries from cooperating with Chinese firms in sensitive sectors.

At the same time, Chinese companies showed an interest in Ukraine’s mineral wealth already before 2022. Chengxin Lithium, for instance, had formally applied for exploration rights to Ukrainian lithium deposits. These projects were suspended by the war, but the implication is that such interests could resurface during post-war reconstruction, particularly as global competition for CRMs intensifies. For Kyiv, this sector presents both an opportunity and a challenge. The new mineral deal strengthens US oversight, constraining Chinese investments, yet over-reliance on a single partner could undermine Ukraine’s strategic autonomy and sovereignty. For the EU and CEE, it is important to understand that the China-Ukraine economic nexus intersects with wider debates about de-risking and supply chain security.

Reconstruction and Strategic Autonomy

Post-war reconstruction will likely see competition between Western and Chinese firms for contracts in infrastructure, energy, and technology. President Zelenskyy, however, has made clear that only countries supporting Ukraine during the war will be welcomed as guarantors – effectively excluding China. This stance will also shape the economic dimension of reconstruction, which, despite the ongoing war, has never ceased, yet Chinese companies remain largely absent. Chinese companies have already started traveling to Kyiv for reconstruction talks, though they mostly represent smaller private firms rather than the state-owned giants typically tied to the Belt and Road Initiative.

How Kyiv manages CRM concessions, export controls, and investment screening will be critical for aligning its economic recovery with long-term security objectives. The challenge lies in fully integrating into Western economic and security structures while sustaining a transactional yet significant relationship with Beijing. A SWOT analysis by the Ukrainian Association of Sinologists highlights both the promises and the pitfalls of this relationship. Strengths and opportunities include the scale of the Chinese market, the potential for investment in infrastructure, renewable energy, and agriculture, and participation in global value chains. At the same time, weaknesses and threats remain stark, ranging from political asymmetry and limited dialogue to China’s comprehensive strategic partnership with Russia, ongoing war risks, and US-China rivalry.

At present, Ukraine has little to no real leverage over China. Although China remains Ukraine’s largest trading partner, the relationship is heavily imbalanced. The expansion of Ukraine’s agricultural exports to China has been hindered by protracted veterinary, sanitary, and phytosanitary procedures, repeatedly delayed by the Chinese side – first under the pretext of the COVID-19 restrictions, now shaped by political considerations. Kyiv’s survival strategy thus continues to depend on international assistance and solidarity.

Watching the recent military parade in Beijing, where Xi Jinping stood alongside Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong Un, it is evident that China is unlikely to exert direct pressure on Russia or embrace Ukraine’s definition of peace. Instead, Beijing will continue emphasizing its commitment to nuclear non-proliferation and engaging primarily through multilateral fora such as the United Nations. Any meaningful pressure on Russia would require coordinated action by all nuclear powers – a scenario in which China may participate, but not lead, let alone act unilaterally.

Written by

Vita Golod

VitaGolodVita Golod, Ph.D. is a Junior Research Fellow at the A. Krymskyi Institute of Oriental Studies, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, and a Visiting Instructor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.