This article is a translation of the German-language memo “Chinas Privatunternehmen unter ‘Xiconomics’” by Kai von Carnap, published by the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) in May 2025.

China’s tech champions often emphasize their independence, yet the party-state has installed mechanisms – party cells, golden shares, and pressure tactics – that make genuine autonomy doubtful. In Europe, the Chinese Communist Party’s far-reaching control over Chinese firms remains largely under the radar. Tools such as the FDI screening mechanism urgently need to incorporate political-influence indicators if they are to capture state-directed control accurately.

The “-ism” of Xi – akin to “Reaganomics” or “Thatcherism” – welds his name to an entire economic creed. Under the blueprint of “Xiconomics,” China’s economy was recast as state capitalism, characterized by deep intervention into private-sector structures and tighter limits on entrepreneurial autonomy. The Communist Party’s co-optation of private firms is nothing new, but under Xi Jinping –and his vision of “modern private enterprises with Chinese characteristics” – it has intensified dramatically.

The opaque nature of these political influence channels impedes realistic risk assessments for security-sensitive investments and technology partnerships. For example, authorities in Germany – and, by extension, Europe – will need to monitor the evolution of Chinese firms closely and recalibrate their regulatory toolkits. The new federal German government is duty-bound to do so, not only because the EU’s recently expanded NIS2 Directive, effective since 17 April 2025, imposes mandatory cybersecurity and incident-reporting rules on 18 critical sectors, but also because the 2025 coalition agreement pledges to implement the forthcoming Cyber Resilience Act.

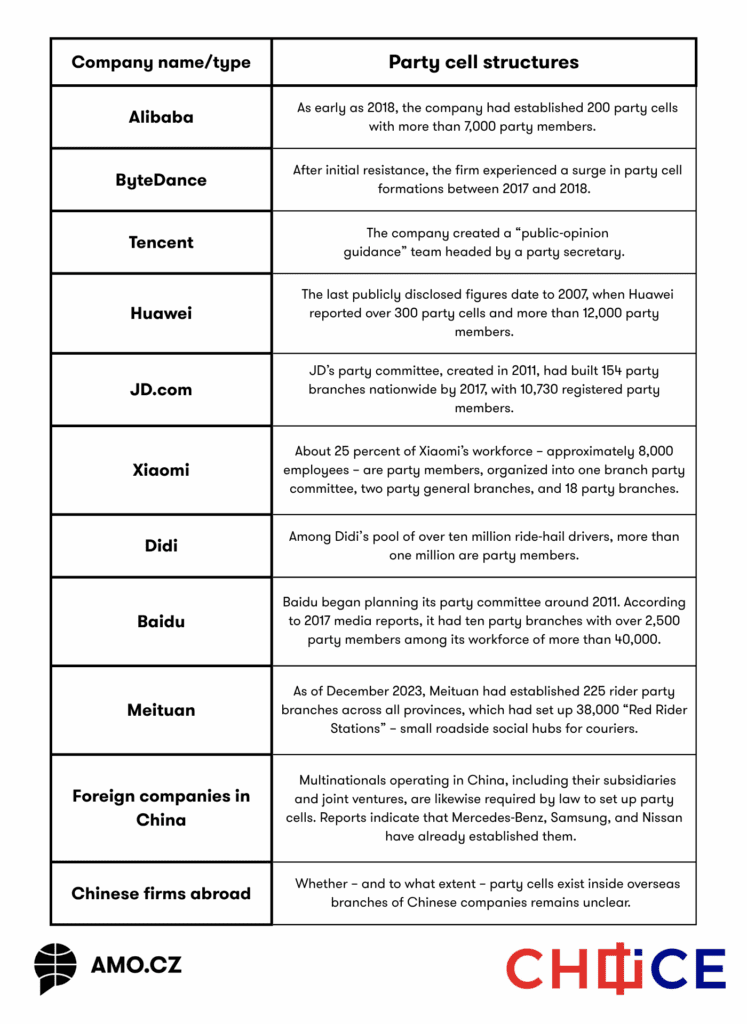

How Party Cells Operate Inside Chinese Companies

Since 1993, China’s Company Law had governed the Communist Party representative units within private firms. A 2005 amendment made the establishment of such units – commonly known as “party cells” – mandatory. However, it was not until a series of policy initiatives in 2018 and 2020 under Xi Jinping that the expansion of these units significantly deepened.

Today, party cells are creative and multifaceted structures: at least seven different types of cells can be formed, often numbering several or even hundreds within a single company. Depending on the firm’s size and the number of party members on its payroll, these structures range from shopfloor “grass-roots” groups to board-level units.

The rollout of party cells is a core element of what Beijing calls “party construction work,” overseen by the party’s United Front apparatus and turbo-charged by Huawei’s “Smart Party Building” programs – IT-driven platforms for digitally managing and training cadres. The cells’ remit is broad: ensuring regulatory compliance, providing ideological instruction for the workforce, and policing loyalty to the party. In some cases, they create access to state capital or serve as levers to steer executive decisions.

By 2023, official figures reported 1.6 million party cells embedded in Chinese private companies. Penetration rates across sectors average above 90 percent; however, experts estimate that in the technology industry, the figure is close to 100 percent (see Table 1 for examples).

Table 1: Examples of companies and their party cell structures:

Sources for table 1: Alibaba; ByteDance; Tencent; Huawei; JD.com; Xiaomi; Didi; Baidu; Meituan; Foreign companies in China

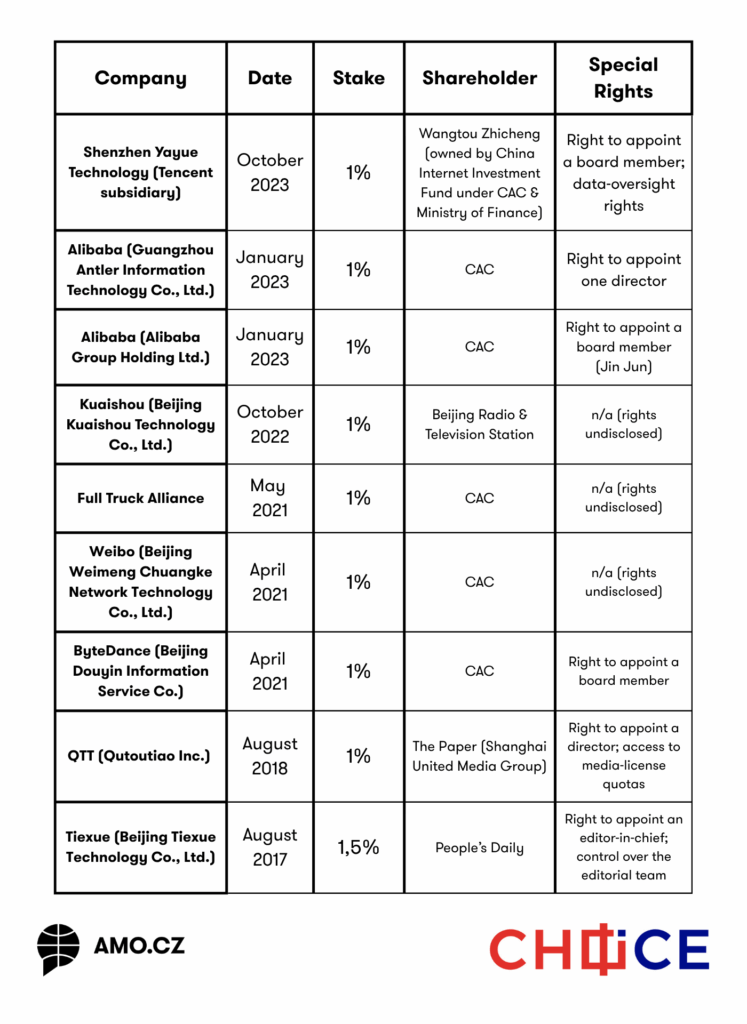

Golden Shares: Special Rights for Minimal Equity

“Golden shares” originated in 1980s Britain, when Margaret Thatcher’s government sought to retain a strategic veto in privatized industries. Since 2013, a similar tool has surfaced in China. These shares – sometimes referred to as “special management shares” – allow the state to wield outsized powers while holding only a minority equity stake. Rights can include appointing a board director, vetoing specific corporate decisions, censoring content, or securing access to essential media and publishing licenses. The details are often murky. Golden shares are rarely issued directly to a ministry; instead, they are channeled through layered corporate structures such as the China Internet Investment Fund (CIIF). What is clear is that companies allocate such shares to a government entity, and the resulting privileges are typically exercised by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC).

No definitive count exists, but analysts believe the number remains limited and aimed chiefly at tightening control over the data and content pipelines of China’s most influential internet firms. Alongside rumors involving Tencent, 36Kr, Didi, and Ximalaya, as well as unspecific reporting around SenseTime, confirmed cases are listed in Table 2.

Table 2: Confirmed cases of companies with special rights:

Sources for table 2: Shenzhen Yayue Technology (Tencent subsidiary) [1], Alibaba (Guangzhou Antler Information Technology Co., Ltd.) [1], [2], Alibaba (Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.) [1], Kuaishou (Beijing Kuaishou Technology Co., Ltd.) [1], Full Truck Alliance [1], Weibo (Beijing Weimeng Chuangke Network Technology Co., Ltd.) [1], ByteDance (Beijing Douyin Information Service Co.) [1], QTT (Qutoutiao Inc.) [1], Tiexue (Beijing Tiexue Technology Co., Ltd.) [1]

Formal and Informal Pressure Tactics

Beijing leans on a broad arsenal to tighten its grip on private tech firms. Formal interviews, convened by CAC or other regulators, are an increasingly common tool. In the first 500 days after the 2017 Cybersecurity Law took effect, officials held 1,998 such sessions – urging companies to fall in line and avoid sanctions. The numbers keep climbing: 8,608 interviews in 2022, 10,646 in 2023, and 11,159 in 2024. Alongside these documented sit-downs are the more discreet “tea chats” – confidential meetings where officials firmly remind executives of policy red lines.

Both formats can end in very public acts of contrition. In 2018, ByteDance founder Zhang Yiming issued a self-criticism letter that read like a Mao-era confession, admitting moderation errors, pledging loyalty to socialist core values, and bemoaning his personal failures. High-profile resignations or disappearances have also become more frequent: Ant Financial’s Peng Lei, Pinduoduo’s Colin Huang, and Yidao Yongche’s Zhou Hang all vanished from the spotlight or stepped down, only to reappear after a period of “rectification.” The most memorable case, however, is Alibaba founder Jack Ma. After a 2020 speech that criticized regulators, Ma disappeared for three months. Dethroned, he spent years on the periphery of public attention, only to resurface in early 2025 in state media as a model loyalist – just as a French court began reviewing transcripts alleging he had intimidated an expatriate businessman at the party’s behest.

What Germany and Europe Should Do

If political influence channels remain invisible, Germany risks misjudging security-critical investments and technology partnerships. Before core infrastructures – 5G, cloud services, artificial intelligence – are built on suppliers that can be weaponized at a moment of geopolitical crisis, regulators must know whether these firms are effectively controlled by the Chinese Communist Party. At the same time, Chinese companies that have genuinely slipped Beijing’s political grasp should not be unfairly treated.

So far, informal or party-political leverage has escaped the scrutiny of key German bodies, such as the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWK), the Federal Office for Economic Affairs and Export Control (BAFA), and the Federal Office for Information Security (BSI). Legal frameworks and political debates still focus almost exclusively on ownership structures and subsidies. That lens must widen to reflect the shrinking autonomy of Chinese conglomerates.

During the ongoing slow removal of Huawei and ZTE gear from Germany’s 5G core (scheduled to finish in 2026, with full network clearance by 2029), vendors should be required to disclose party affiliations and any golden shares, and to meet expanded supply-chain transparency rules under the forthcoming IT Security Act 2.0. In addition, under the new leadership, the ministry should use the next revision of the FDI screening mechanism (AWG/AWV) to extend investment reviews explicitly to informal influence structures – party cells and golden shares included. Furthermore, the fourth BMWK/BAFA measures package, in force since 15 January 2025, introduces new open general licenses for dual-use goods and software and streamlines procedures. It offers another lever for probing hidden channels of control. Only by systematically identifying and disclosing political influence – wherever it originates – can Germany ensure that economic policy rests on clear criteria rather than covert steering interests.

Written by

Kai von Carnap

kavocaboKai von Carnap is a Research Associate as part of the project “Digital Sovereignty of Europe (DigitS EU)” at the University of Trier. He is pursuing a PhD where he focuses on global internet governance and the interplay between digital technologies and state power. He is also an Associate Fellow at the Center for Geopolitics, Geoeconomics, and Technology at the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP), as well as a BLOCS Lab Fellow at the Aletheia Research Institution.