Understanding the Czech Approach Towards the Indo-Pacific

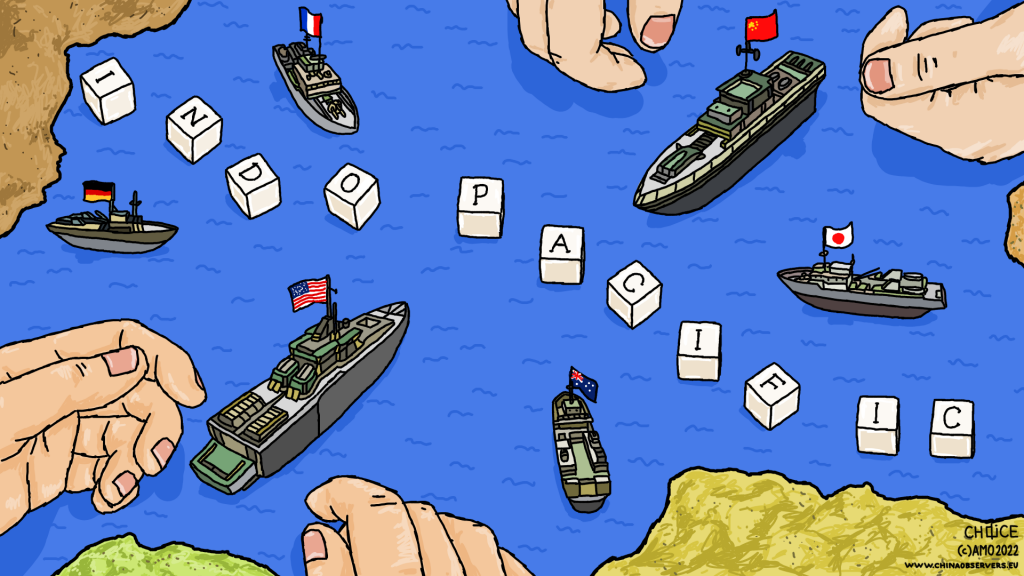

As the Czech Republic prepares to assume the presidency of the Council of the European Union in July 2022, engagement in the Indo-Pacific will be one of the key issues on the agenda.

This article is part of a series of articles authored by young, aspiring China scholars under the Future CHOICE initiative.

The European Union’s stronger geopolitical interest in the region materialized in 2021 with the Indo-Pacific strategy, of which France has been the leading force. French President Emmanuel Macron already presented his approach to the Indo-Pacific back in 2018, making France the first European country to articulate this regional framework. Increasing the involvement in the Indo-Pacific has also been one of the key points of the program for the ongoing French Presidency of the Council of the European Union.

Making the Most out of Insecurity

Compared to France, the Czech Republic’s commitment to the Indo-Pacific can initially seem weakly motivated. France’s complex military presence in the Indo-Pacific and China’s growing influence on Paris’ overseas territories in the region (as in the case of French Polynesia) are logical incentives for the country’s regional interest. In the case of geographically distant and landlocked countries such as the Czech Republic, the rationale is less immediately clear.

In practice, however, the Czech Republic is already closely cooperating with various Indo-Pacific countries and not just with China, officially a strategic partner since 2016. Among them, South Korea was the first Asian country to establish a strategic partnership with the Czech Republic in 2015, although scientific cooperation agreements were established much earlier, in 1995. Relations with Japan have also been warm, not at least due to the key role of Japan as an investor in the Czech Republic. In 2003, the two countries signed a joint statement toward a strategic partnership, and in 2021 the governments further defined the areas of cooperation with the Action Plan for Cooperation. During the Czech-Indian Online Bilateral Dialogue of December 2021, the Deputy Minister of Defense of the Czech Republic Jan Havránek also encouraged the further strengthening of India-Czech Republic bilateral ties.

The progressive engagement with the region has already won the Czech Republic a lot of visibility, especially in the field of technology and security cooperation. The Czech Republic gave proof of its commitment to the Indo-Pacific cause early on, immediately after the EU’s joint statement. First, it appointed the experienced Libor Sečka, former Ambassador to China and the United Kingdom, as the new Special Envoy for the Indo-Pacific. Then, in November 2021, it started a series of official talks with Indian and Indonesian representatives, establishing strengthened bilateral relations in the field of security and innovation. Already in 2020, the two countries were the main export destinations for Czech arms manufacturers, surpassing China by a large amount. National champions like ELDIS (a Czech radar manufacturer company), are currently selling their devices to the Indian Navy and Coast Guard. Similarly, the Czech Excalibur started the production of rocket launchers for the Indonesian army.

But the Indo-Pacific strategy is not only about security cooperation, and not every country has the resources to have a strong security commitment in the region. Green transition, digital governance, and connectivity are also among the priority areas, that the Czech presidency will be grappling with.

One Door Closes, Another One Opens?

Czechia’s increasingly close ties with Indo-Pacific partners stand in contrast to the troubled relationship with China. While China was designated a strategic partner in 2016, by 2019, the Czech Republic had already started distancing itself from Beijing. Unsatisfying levels of investment, influence scandals, and general disillusionment with the 16+1 platform fueled the debate and resulted in the country reconsidering its relationship with China. Last October’s change of government, now led by Prime Minister Petr Fiala with a China-skeptical foreign minister, Jan Lipavský, has further pushed the country away from China’s orbit.

Along with distancing itself from China, Prague has shown a growing interest in building ties with Taiwan. The issue has quickly become a contentious one in domestic politics. Senate President Vystrčil visited Taiwan in 2020 in the highest-level visit to the island by a Czech representative, making a strong signal of support. The action was welcomed positively by the Taiwanese public and reciprocated by minister Joseph Wu and his delegation’s unofficial visits to the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Poland, and Lithuania.

On the other hand, President Miloš Zeman has maintained a China-friendly posture, undermining some of the efforts to rebalance the relationship. In 2019, Zeman showed support to Huawei against the allegations of spying activities the US made against the company, and after Vystrčil visited Taiwan he defined his trip as a “childish provocation,” deciding to disinvite him from meetings of the highest Czech constitutional representatives on foreign policy. Meanwhile, practical cooperation with Taiwan has continued as in 2021, Taiwan and the Czech Republic signed a series of MOUs covering various fields, including cybersecurity. In 2022, the agreements were finalized with the establishment of the $200 million Taiwan’s Central and Eastern Europe Investment Fund. The new government with Foreign Minister Jan Lipavský has clearly signaled its support of Taiwan, although no clear policy change has so far been announced.

Many in Czechia see Taiwan as a promising partner, for example, on the issue of developing a toolkit of countermeasures against propaganda and disinformation.

According to Marc Cheng, Executive Director of the EUTW Center, both Central-Eastern European countries and Taiwan share the common faith of being at the frontier of disinformation. “We have a common interest in studying threats to democracy, as we are both facing neighbors that could interfere with the society’s stability by using disinformation.”

Cheng also highlights the importance of the Czech Republic as a research hub for disinformation on the continent, and adds that “the European Union and the Indo-Pacific can work together, and learn from each other to work out feasible solutions applicable to other countries facing similar challenges.”

Opportunities Abound

The war in Ukraine and the subsequent shift in EU priority policies can be a test of political will for the Czech Republic. If resources permit, there are many reasons to expect the country to keep up with its initial commitment to the Indo-Pacific. The Czech Republic’s interest in not restricted to the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy and is motivated by both economic interest, and the domestic political environment, especially in the case of Taiwan.

Even without a navy, it is becoming increasingly evident that the Czech Republic has reasons to get involved in the Indo-Pacific. On the one hand, the country is proving to be an increasingly relevant partner in the region in terms of defense cooperation. On the other hand, its decades-long experience with foreign influence gives the country the right expertise to contribute to the EU strategy with non-standard military means, as in the case of counterintelligence and disinformation monitoring.

The comprehensive nature of the Indo-Pacific strategy also encourages cooperation outside of the hard security domain. The Member States without the means (or interest) to contribute to traditional security, can find room for an initiative in other fields such as connectivity, and trade. Considering the sanctions on Russian exports, the Czech Republic and other smaller EU member states could also gain additional motivation to enlarge their footprint in the region, which now seems closer to Europe than ever before.

Written by

Lucia Gragnani

LuciaGragnaniLucia Gragnani is Junior Researcher at Taiwan NextGen Foundation. She previously studied Chinese at Bologna University and the National Taiwan University in Taipei.