UN Bodies as a Geopolitical Arena: Southeast Europe’s Alignment on China?

This article is based on a policy paper “Navigating Multipolarity: Southeast Europe in the EU’s China Strategy“ by Ana Krstinovska, Zlatko Simonovski, Plamen Tonchev and Stefan Vladisavljev, originally published by Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies.

Within the United Nations (UN) system, China has shown a steadily growing readiness and capacity to engage across a broad spectrum of thematic areas, occasionally assuming a leading role. Southeast European (SEE) countries such as Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Greece, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia are not spared from these tendencies too. Nevertheless, Beijing’s principal focus continues to revolve around issues directly linked to its domestic governance and territorial integrity, especially on Taiwan, Tibet, Hong Kong, and, in recent years, Xinjiang where the overarching concern remains human rights.

China’s ability to leverage its political and economic weight within the UN architecture has made the formal adoption of resolutions critical of its human rights practices highly unlikely. Consequently, groups of member states have relied increasingly on joint statements, usually delivered at forums such as the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) and the Third Committee of the UN General Assembly (UNGA), as a means of expressing collective positions. Western statements aim to condemn China’s human rights record, especially in relation to Xinjiang and Hong Kong, whereas counter statements, primarily led by the Global South states such as Algeria, Cuba, Venezuela, Pakistan, or Belarus, offer explicit support to China, rejecting external criticism over human rights as interference in domestic affairs.

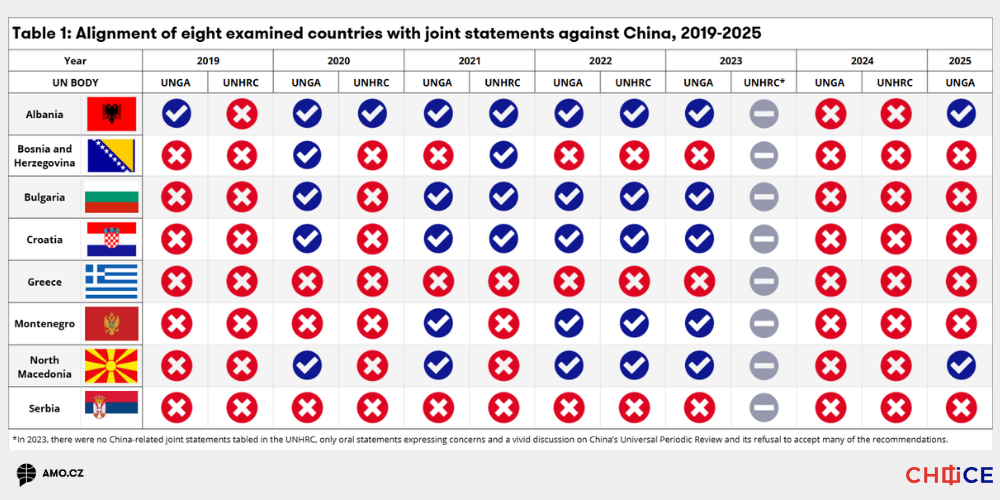

Alignment at the UNHRC

Across the six-year period of 2019-2024, SEE countries exhibited a selective and shifting pattern of engagement at the UNHRC in relation to joint statements addressing China’s human rights record. Albania was the most consistent among them, supporting Western-led initiatives in four consecutive years, from 2020 through 2023, before stepping back in 2024. Bulgaria, Croatia, and North Macedonia followed similar trajectories, aligning during the mid-period (2021–2023) but disengaging afterward. Bosnia and Herzegovina’s alignment was limited to 2021, while Montenegro joined only in 2022 and 2023, suggesting episodic rather than sustained commitment. On the other hand, Greece maintained a position of complete absence throughout the entire timeframe, avoiding any formal endorsement of statements critical of China.

Alignment at the UNGA

Patterns at the UNGA mirrored, though slightly preceded, the trends observed at the UNHRC. Albania was again among the earliest participants, joining the 2019 UK-sponsored joint statement in the Third Committee. In subsequent years, Croatia, Bulgaria, and North Macedonia joined the group of signatories, while Bosnia and Herzegovina aligned only in 2020 and 2021. Montenegro entered the fold later, aligning from 2021 to 2023, whereas Greece consistently refrained from joining. The collective momentum in support of Western-led statements peaked between 2021 and 2023, when a majority of SEE countries signed joint declarations criticizing China’s human rights practices in Xinjiang and Hong Kong. However, by 2024, this trend reversed entirely, with none of the countries aligning with the statements delivered by the US or Australia. This withdrawal suggests growing sensitivity to geopolitical pressure, as well as the perception that continued participation could jeopardize economic or political relations with Beijing. The pattern also reveals a pragmatic regional approach, viewing UNGA alignment less as a normative commitment and more as a tactical choice amid a complex international environment, wait-and-see attitudes visible ahead of the 2024 US presidential elections, and the uncertainties in the global economy.

Serbia as a “Sui Generis” Case

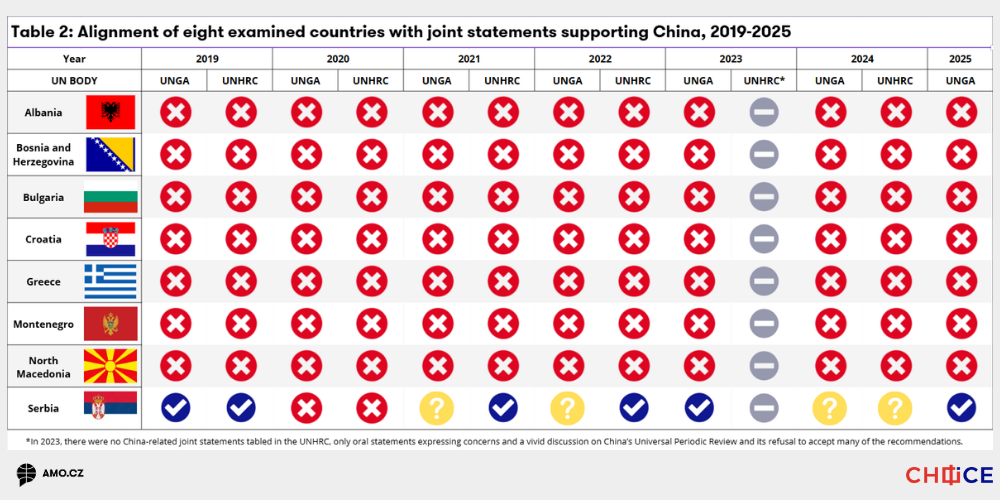

Serbia represents a distinct and consistent outlier within the SEE group. Unlike its neighbors, Belgrade has never joined any statement condemning China at either the UNHRC or UNGA. On the contrary, it has repeatedly endorsed counter-statements defending Beijing’s human rights policies and sovereignty claims, aligning with positions advanced by China and its allies. Serbia co-signed the Chinese-led statements at the UNHRC in 2019 and 2021, rejecting Western criticism of China’s treatment of Uyghurs and emphasizing the principle of non-interference in domestic affairs. Its voting record at the UNGA also reflects this orientation: Serbia was among the very few European countries to vote in favor of a 2021 resolution promoting international cooperation on the peaceful uses of science and technology, an initiative widely seen as advancing China’s diplomatic agenda. This consistent alignment underscores Serbia’s broader foreign policy strategy of balancing Western engagement with strategic partnership with Beijing. This hedging behavior is primarily due to the fact that China does not recognize Kosovo as an independent state but considers it a part of Serbia. On the other hand this period coincides with China’s massive investments in Serbia, leading to Chinese companies topping the FDI list in 2021 and ranking second place in the cumulative FDI inflow in 2008-2023, right after the US.

However, as it can be observed from Table 2, for several years within the examined period, solely in relation to the counter-statements supporting China, the official lists of signatories are either incomplete or not publicly accessible. In these cases (marked by question marks in the table) the precise composition of supporting states cannot be independently verified through the UN records or national statements. Nonetheless, both Chinese official sources and statements by the sponsors of these counter-initiatives have consistently asserted that the number of countries endorsing pro-China declarations has been rising over time. Although the lack of transparency complicates the assessment of the actual scale of alignment, the narrative of expanding support serves an important political function, reinforcing China’s portrayal of growing Global South solidarity and legitimizing its positions in multilateral forums.

The Rationale for the “Ups and Downs”

The voting patterns of SEE countries within the UN underscore a region marked by strategic pluralism rather than coherent alignment. Instead of adhering strictly to either Western or Chinese blocs, most SEE states calibrate their positions according to a mix of security, economic, and diplomatic considerations. Alignment in multilateral arenas is thus viewed less as a reflection of ideological conviction and more as an adaptable tool of foreign policy maneuver.

For Albania, “carte blanche” participation in West-sponsored statements aligns with its firm Euro-Atlantic identity and the aspiration to prove reliability as both a NATO ally and soon to be EU member. Though absenting from the “Western list” in 2024, the country together with North Macedonia came back in last autumn’s Joint Statement on the Human Rights Situation in China sponsored by the US. Croatia, Bulgaria, and North Macedonia share similar motivations seeking to consolidate their standing within the EU and maintain good relations with the US, while at the same time playing cautious amid growing awareness of Beijing’s economic leverage and the potential costs of open confrontation. Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro, whose internal politics and external dependencies are more fluid, mostly due to the significant Serbian influence, display sporadic support. This is especially valid for Bosnia and Herzegovina as Republika Srpska’s officials and establishments tend to “pull the Chinese card” when confrontation with the Federation is on the “agenda.” Greece, bound to China through major infrastructure investments such as the Port of Piraeus, has maintained consistent neutrality, prioritizing economic and political pragmatism over flirting with either side. Serbia, in contrast, represents a singular case within the region. with its enduring solidarity with China reflecting a calculated diplomatic strategy, anchored in reciprocal support over Kosovo, substantial Chinese investment, and a shared narrative of sovereignty and non-interference. Taken together, SEE states regard alignment in the UN as a matter of selective engagement rather than an obligation, practicing pragmatic regional diplomacy that balances Western expectations with the realities of Chinese influence.

These dynamics suggest that (non-)alignment with China is shaped far more by calculation than by ideological affinity. SEE states weigh economic exposure, strategic dependencies, and diplomatic costs when choosing whether to align, particularly in multilateral settings where participation remains voluntary. In the UN, this logic has increasingly favored Beijing, allowing China to consolidate support and sharp human rights scrutiny, while Western-led criticism loses pace. In such a geopolitical context, alignment can no longer be dismissed as merely symbolic as even selective or tacit support may carry strategic weight, shaping narratives, coalitions, and the future balance of influence in international institutions.

Written by

Zlatko Simonovski

Zlatko Simonovski, MA is a former journalist with strong experience in investigative reporting, media integrity, and geopolitical analysis. He has worked in newsroom environments where quick verification, ethical decision-making, and resistance to pressure are crucial. From a geopolitical perspective, he focuses on EU–China relations and the EU integration process of the Western Balkan countries, examining the internal and external factors shaping its pace and trajectory.