Two Sessions: China’s Foreign, Economic and Social Policy Priorities for 2025

The annually held ‘Two Sessions’ – the concurrent meetings of the National People’s Congress (NPC), China’s rubber-stamp parliament, and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), an institution often regarded as even more powerless – concluded on March 11, after a week of speeches, press conferences and side meetings between government officials, members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), academics, industry leaders and various other delegates. As usual, significant attention was paid to the Government Work Report presented by Chinese Premier Li Qiang, which outlined the policy priorities for the coming year, including the annual GDP target. These priorities were largely determined long before the sessions took place, as the Two Sessions serve mainly as a platform to announce and confirm existing decisions.

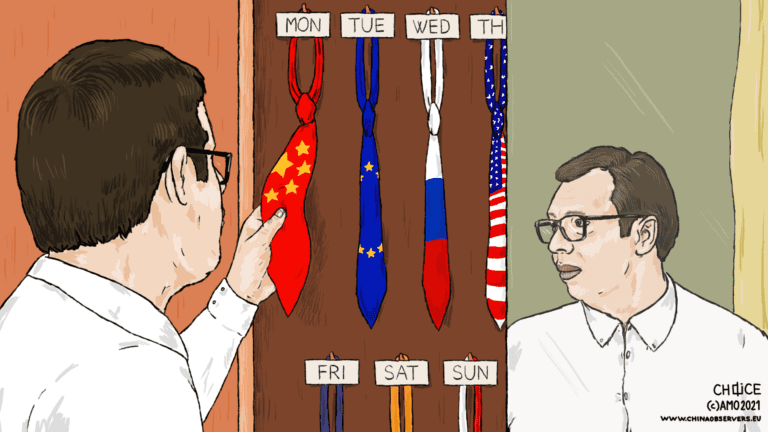

As this year’s Two Sessions took place against the backdrop of deteriorating relations not only between China and the US but also the US and the EU, rising protectionist tendencies and a rapidly changing international order, we have asked our analysts to provide insights into these sessions, focusing on their implications for foreign, economic, and social policies in China.

Chu Yang

China Analyst at the Association for International Affairs (AMO), Denmark

Amidst unprecedented political turbulence in the United States, China’s annual Two Sessions convened against the backdrop of escalating trade tensions. President Trump’s recent decision to double tariffs on Chinese imports to 20 percent sent shockwaves through global markets, whereas his confrontational meeting with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy devolved into a verbal exchange that many observers characterized as “one of the greatest diplomatic disasters in modern history,” leaving many questioning America’s reliability as a partner. This diplomatic chaos created a strategic opening for Beijing to position itself as a stabilizing force on the world stage.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi seized this opportunity during his high-profile press conference, characterizing certainty as “a scarce resource” in today’s chaotic world. Wang articulated China’s determination to stand “on the right side of history” while defending national interests against “maximum pressure, threats, or blackmail.” His remarks directly countered the unpredictability emanating from Washington. China’s newly appointed Special Representative for European Affairs, Lu Shaye, further expressed Beijing’s position on Ukraine by stating that while China appreciates US-Russia contact, “the Ukraine peace process cannot be determined solely by the US and Russia – at least Europe has strong opinions on this matter.”

The Two Sessions’ economic agenda further highlighted how China intends to leverage the perceived instability of the US. Premier Li Qiang’s Government Work Report emphasized “expanding high-level opening up” and “actively stabilizing foreign trade and investment” despite external challenges. Specific focus was given to the Private Economy Promotion Law and urban renewal initiatives as tools to boost domestic consumption while attracting foreign investment. This economic strategy reflects Beijing’s pragmatic approach – using foreign capital and trade as critical levers for domestic growth while positioning China as an alternative center of global stability. Shanghai’s achievement as the world’s busiest container port for fifteen consecutive years was presented as evidence that China continues to offer “more opportunities than challenges” for international partners seeking certainty in an increasingly unpredictable global environment.

As global businesses watch the unpredictable American foreign policy play out on television, Beijing hopes to position itself as the more reliable partner, offering stability and certainty. In doing so, it seeks to transform geopolitical tension into economic opportunity as part of China’s strategy to revitalize its economy, especially amidst ongoing challenges in the property sector and consumption.

Dominika Remžová

China Analyst at the Association for International Affairs (AMO), Czech Republic

With several of the announced targets and policies remaining the same as last year – namely the five percent GDP growth target and the seven percent increase in the defense budget – major attention was paid to the growing (rhetorical) focus on boosting consumption and supporting the private sector, as seen in the widely discussed Private Economy Promotion Law. And while the draft has not yet passed into law, the ongoing amendments imply a growing commitment to improving the business environment, as well as an acknowledgment by the Chinese leadership of the importance of private companies for the country’s economic growth. This is underscored by the rapid emergence of DeepSeek and its implications for Chinese AI development (with AI being one of the high-tech “productive forces” intended to spur future economic growth) – developments that are even more significant against the backdrop of the rising US-China tech war.

Yet, despite several other announcements of stimulus measures aimed at achieving the announced growth target, including the historically high fiscal deficit ratio of four percent, concerns persist about China’s ability to meet the target. Chief among these are ideological opposition to structural reforms and difficulties in implementing the proposed policies, such as the reliance on the notoriously unreliable local governments to drive consumption and deep-seated concerns about rising government debt. Nevertheless, the policies underscore that a consumer-driven economy remains the party-state’s long-term goal; all of which was already implied in February, when Xi Jinping held a widely publicized meeting with private sector entrepreneurs.

While economic growth remains the top priority, climate and energy policies are increasingly deprioritized, a trend that mirrors developments in the US and Europe. At the same time, as Beijing seeks to balance decarbonization (largely driven by green tech developments) with energy security (which, in China’s case, necessitates continued coal consumption), the current geopolitical climate is pushing Beijing to prioritize the latter even more than before. Both the Government Work Report and the report by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) confirm this, along with a continued commitment to fossil-fuel infrastructure, albeit in a “supporting role.”

Several analysts have also agreed that China is likely to miss its current energy and carbon intensity targets, with the latter not appearing in the Government Work Report. That said, as long as the Chinese leadership continues to view green technologies as a driver of future economic growth, China will continue decarbonizing – albeit at a slower pace than some may have expected.

Filip Noubel

China Analyst at the Association for International Affairs (AMO), Taiwan

In Xi Jinping’s ‘China Dream’ – a grand vision for China’s future – 500 million Chinese people are expected to achieve the much-coveted status of middle class as soon as possible. In this scenario, social stability would increasingly align with the interests of those who stand to lose the most in case of political instability. As a result, the CCP’s hold on power is even less likely to be challenged.

One of the cornerstones of the middle class in a market economy is access to decent home ownership. This is why, starting around 2000, real estate developers saw rapid growth, transforming the sector into one of the most profitable economic bubbles in China. Buying an apartment became every family’s dream, and for the wealthier ones, a safe investment. Moreover, the CCP could claim credit for significant GDP growth driven by this boom.

Today, however, the real estate sector has become more of a swamp. The largest developers require financial bailouts, ghost cities filled with empty buildings are proliferating, and yet prices remain high. More worryingly, young Chinese people are either uninterested in buying homes or simply unable to do so.

It comes thus as no surprise that one of the main topics of this year’s National People’s Congress was labeled the “sustainable urban renewal model.” The big idea is to provide decent housing for the millions of people who have migrated to larger cities but live in substandard conditions on the outskirts. The Party wants to show that it cares about its citizens, signaling that it can no longer rely on the struggling real estate sector. Instead, it plans to direct new investments toward improving living conditions and reducing socio-economic disparities; all while maintaining a five percent GDP growth target.

Written by

Filip Noubel

nasredinhojaFilip Noubel is Senior China Analyst at AMO, where he specializes in Chinese domestic politics and society and Cross-Strait (China-Taiwan) relations. He has more than three decades of research experience focusing on China. Filip has experiences as an analyst, commentator, journalist, interpreter and consultant for various organizations, including International Crisis Group, Institute of War and Peace Reporting, International Center for Communication Development, Global Voices, etc. Filip Noubel received the DEA (Diplôme d'Études Approfondies) at the National Institute of Oriental Languages and Cultures (INALCO) in Paris. He also studied at the Central University for Minorities in Beijing.

Dominika Remžová

DominikaRemzovaDominika Remžová is a China Analyst at AMO, specializing in Chinese economy and industrial policy, supply chains, critical raw materials, electric vehicles and, more generally, Chinese foreign policy. In the past, she contributed to Taiwan Insight and The Diplomat, among others. Dominika is pursuing her PhD in Political Science and International Relations at the University of Nottingham. She earned her Master's degree in Taiwan Studies from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London and her Bachelor's degree in Chinese Studies from the University of Manchester.

Chu Yang

Chu Yang is an analyst at AMO, where she specializes in Chinese political discourse and media ecosystems. Chu worked as a researcher, analyst, and journalist for various research institutions, including China Media Project, Aarhus University, MERICS, Caixin, and also co-founded the Cenci Journalism Project.