While Xi Jinping emerged as an uncontested winner from the Party Congress, he faces significant governance challenges ahead.

Xi Jinping, the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), emerges victorious from the 20th CCP Congress. Everything indicates that his authority has expanded more than most commentators had anticipated. He has introduced four new members to the Politburo’s Standing Committee who are deeply connected to him, and the remaining two are his allies. The Politburo itself and the entire Central Committee are dominated by its supporters.

The abrupt removal from the congress venue during the last day of Hu Jintao (Xi Jinping’s predecessor as General Secretary), even if it was dictated by non-political issues (dementia?), can be assumed to have been deliberately carried out in front of foreign journalists. This is a clear signal that no one can feel safe and has a chilling effect on the rest of the leadership.

The lack of an obvious candidate for a successor in the new leadership also indicates that Xi Jinping is not going to retire at the next party congress in 2027 and plans to rule at least until the 22nd Congress in 2032.

Dream Team

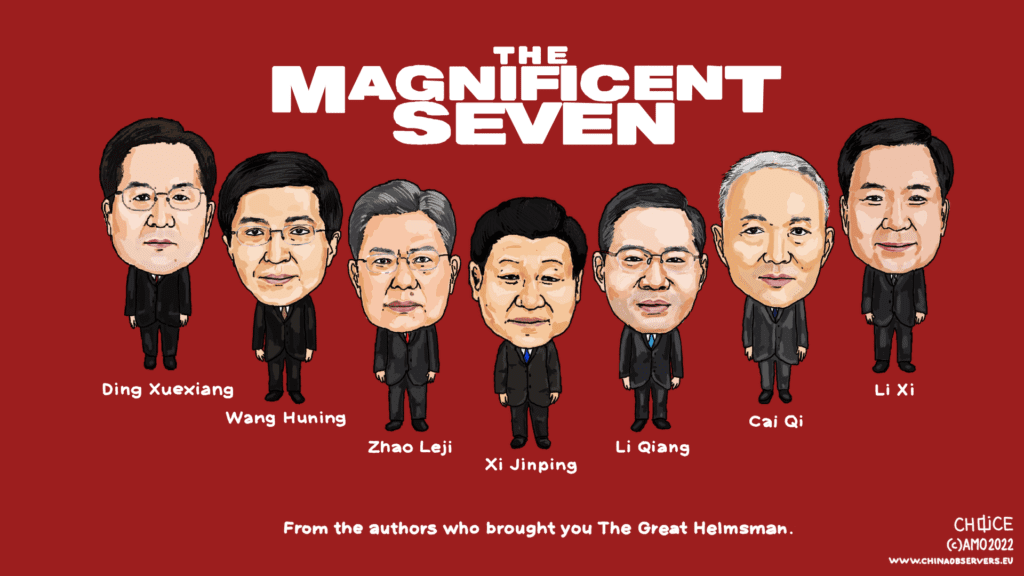

Xi Jinping was not only elected for an unprecedented third term as General Secretary but also introduced a line-up completely made up of his supporters to the Standing Committee of the Politburo, including new members: Li Qiang, Cai Qi, Ding Xuexiang, and Li Xi.

Li Qiang, emerging from the botched lockdown in Shanghai in spring unscathed, will become the new prime minister in March of next year during the session of the National People’s Congress (NPC). In the meantime, it can be expected that he will be quickly appointed deputy prime minister by the Standing Committee of the NPC – the recent amendment of the rules of procedure allows for such a possibility.

Cai Qi, the current party boss in Beijing who has ties to Xi from their time in Fujian, will replace Wang Huning as the first secretary of the secretariat of the Central Committee and will be responsible for organizing the work of the Central Committee. Li Xi, up until now the party chief of Guangdong, becomes head of a powerful anti-corruption body, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, replacing Zhao Leji. Ding Xuexiang, the current Director of the General Office of the CCP who has been one of the closest aides to Xi Jinping, is being touted as deputy prime minister. Zhao Leji, formally number three in the party hierarchy, will lead the NPC, while Wang Huning will take over the People’s Political Consultative Conference, a purely advisory body but important for mobilizing outside support for the party. He will probably oversee the work of the United Front.

The victory and the absolute domination of Xi Jinping’s people and allies at the 20th Congress mean that in the coming years the General Secretary will have no real opposition in the Central Committee. This, however, means that the so far coherent and well-cooperating group of Xi Jinping’s supporters will begin to differentiate internally. This is a natural political process in a situation where there is no unifying factor in the form of an opposition to be fought. Eventually, internal conflicts, rivalry for power, or the leader’s attention will begin to grow. It will be quite a challenge for Xi Jinping to manage the gradual decomposition of his camp and at the same time maintain its cohesiveness and the ability to act in the face of the serious challenges facing the Party and the whole country.

End of the Development Model

The model of China’s development over the past decades has been based – to varying degrees –on three basic elements. The first is the demographic dividend after the famine of the Great Leap Forward, when 600 million people were born within a decade, entering the labor market in the 1980s and 1990s, giving China huge development potential. The second element was the foreign investment flowing to the country since the 1980s and the development of the world-leading export industry. The third factor was the investment in infrastructure, the role of which increased significantly after the 2008 economic crisis when China opted for a huge stimulus. Because for decades, the population’s income grew slower than the GDP, the extending gap was creating extra capital, which was seized by the state and directed to domestic investments, and at the same time, the exports and foreign investments allowed Beijing to dynamically balance the entire system.

Currently, all three closely related elements are slowly disappearing or beginning to generate problems. The population is aging and there is no one to replace the boom generation due to the draconian one-child policy introduced in the early 1980s. As a result, the burden on the pension system is increasing. At the same time, productivity growth declined sharply. Foreign investments are still growing in nominal terms, but their share in GDP has fallen. At the same time, during the pandemic, the share of exports in GDP began to increase again. However, the friendly international situation that made it possible for China to achieve its “economic miracle” is over, due in part to Xi Jinping’s foreign policy. Eventually, the West will start implementing a decoupling program, and the Chinese economy can no longer be so dependent on exports.

With infrastructure investments saturating the most developed parts of China, they are being diverted to the periphery or duplicated. Nowhere, however, do they translate into real changes in the economy. Neither can China sustain a situation in which 45-50 percent of GDP is allocated to investment and de facto only serves to artificially maintain GDP growth. Especially since this exacerbates the economy’s indebtedness, which already in 2019 exceeded 300 percent of GDP. The scale of the hidden debt is difficult even to estimate.

Added to this is the problem of a speculative bubble in the real estate market. On the one hand, hundreds of millions of people cannot afford housing, especially young couples who cannot start a family or are limiting the number of their offspring, exacerbating the demographic crisis. At the same time, China had plans to build a number of housing units that could accommodate 3.4 billion people. Already there are at least 65 million sold but vacant houses, but real estate continues to be a crucial tool to maintain GDP growth. The protests by small savers this summer are linked to the problems of local banks that finance the real estate market, but the entire banking sector that has been lending to the growing bubble for years is one ticking bomb.

In this situation, China faces the task of raising the population’s income to reorient the economy towards domestic consumption, which should replace a sizable portion of exports. Such a development would also relieve social tensions. At the same time, such a move by the central government would abruptly close off a source of cheap capital for infrastructure investment and would put Beijing in conflict with local elites, who are getting rich by controlling the flow of money going into infrastructure and housing.

Against the Party Apparatus and the People

The 20th Congress adopted several amendments to the Party constitution, including those on so-called “dual circulation” and “shared prosperity.” This sends a strong signal that the priority for Xi Jinping in his new term (or two terms) will be to change China’s socio-economic development model. This raises the next two dilemmas.

The first is the time lag between cutting off the flow of capital from infrastructure projects and the point at which the growth of population income and consumption will begin to drive the economy. Several years of stagnation in an authoritarian state risk a social explosion, especially since outside of islands of wealth like Beijing and Shanghai, China is still a low-income country, highly vulnerable to any kind of even short-term economic downturn.

The second issue stemming from the economic transition relates to the dissatisfied local CCP structures and related businesses. It is no secret that the Communist Party suffers from a shortage of idealistic communists, and most cadres are careerists. With the cut-off from the stream of capital that allowed them to get rich, they will lose more than their motivation to act. And without them, the CCP will begin to lose control of society and the economy.

Xi Jinping’s answer to these dilemmas is to re-Stalinize China. Stalinism, understood as an authoritarian governance mechanism, is supposed to allow social stability to be maintained by brutal repression during the transition and prevent social unrest. However, under Stalinism, ideology is a tool for managing and controlling not only society but also, and perhaps especially, the party apparatus. For Xi Jinping to be able to carry out a change in the economic model, he must not only maintain social control but first break the resistance of the party apparatus suddenly cut off from “fast money” and at the same time maintain the ability to use it to effectively govern the country. This will not succeed without absolute control over the security apparatus, which Xi Jinping only gained this year after conducting a purge of the Ministry of Public Security. Seemingly, this looks like a continuation of the anti-corruption campaign that Xi Jinping launched in 2013. However, while then it was about loyalty to the General Secretary, now it is all about fundamentally changing the system and the role of the party apparatus within.

The first step was to break the opposition in the leadership, but that was the easier part of the task. Unraveling the complex web of connections at the local level, identifying key players, and exerting pressure accordingly will be difficult. It will mean a de facto revolution conducted from within but under the banner of stability and sustainability. The failure – likely one – will be a mortal danger for Xi Jinping and his team.

Written by

Michał Bogusz

boguszmichalMichał Bogusz is a China Research Fellow at OSW (Centre for Asian Studies), Warsaw, Poland. He graduated in Political Science from the University of Gdańsk and International Relations from the Renmin University of China in Beijing, and holds a Ph.D. in Political Science. He has spent nearly nine years studying and working in China.