The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and China’s abrasive diplomacy in its aftermath, coupled with a growing Sino-American rivalry, have only deepened the pre-existing distrust between Poland and China.

While Chinese authorities continue to declare their willingness to engage, they find it increasingly difficult due to alleged US pressure on Poland. Moving forward in 2021, no change in this dynamic should be expected, especially as the EU’s policy towards China remains conflicted, the Biden administration likely keeps pressure on China, and Poland’s role for Chinese interests stays limited.

Beyond CAI

Warsaw’s current attitude towards relations with Beijing was illustrated by Poland’s reaction to the rushed negotiations of the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI). In December, it was announced by the European Commission that it was ready to close a deal with Beijing due to the new, promising Chinese concessions. The Commission, however, failed to deliver a draft text of the agreement at the proceedings of the COREPER. Therefore, the ambassador of Poland, among others, raised his objections during the meeting. His statement was later supported by the Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs in a similar message on Twitter, who highlighted the EU’s need to engage in discussion with the newly minted Biden administration and not rush into the deal.

This did not, however, stop negotiations from concluding in principle at the end of December 2020. In January 2021, minister Rau emphasized the direction of Poland’s policy as “interested in developing the best possible, stable relations for mutually beneficial economic and trade cooperation between the European Union and China”. However, he also underlined the criticism of the EC decision to conclude CAI negotiations in principle with: “Nothing would have happened if they were extended over the course of another two or three presidencies”.

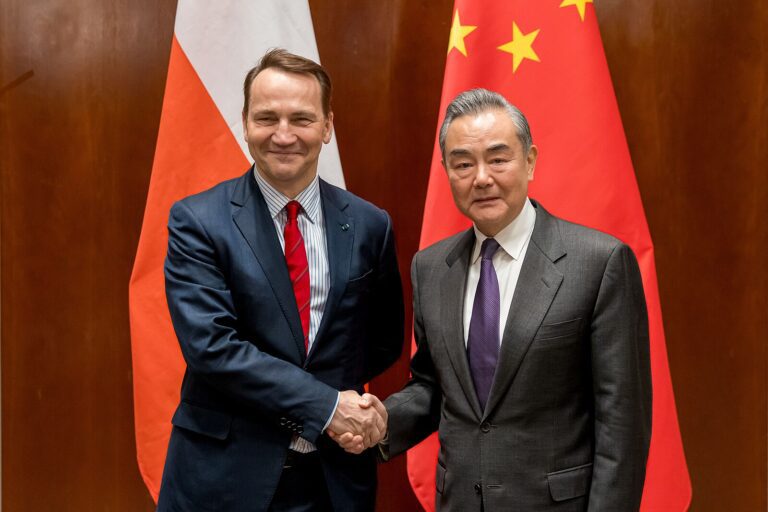

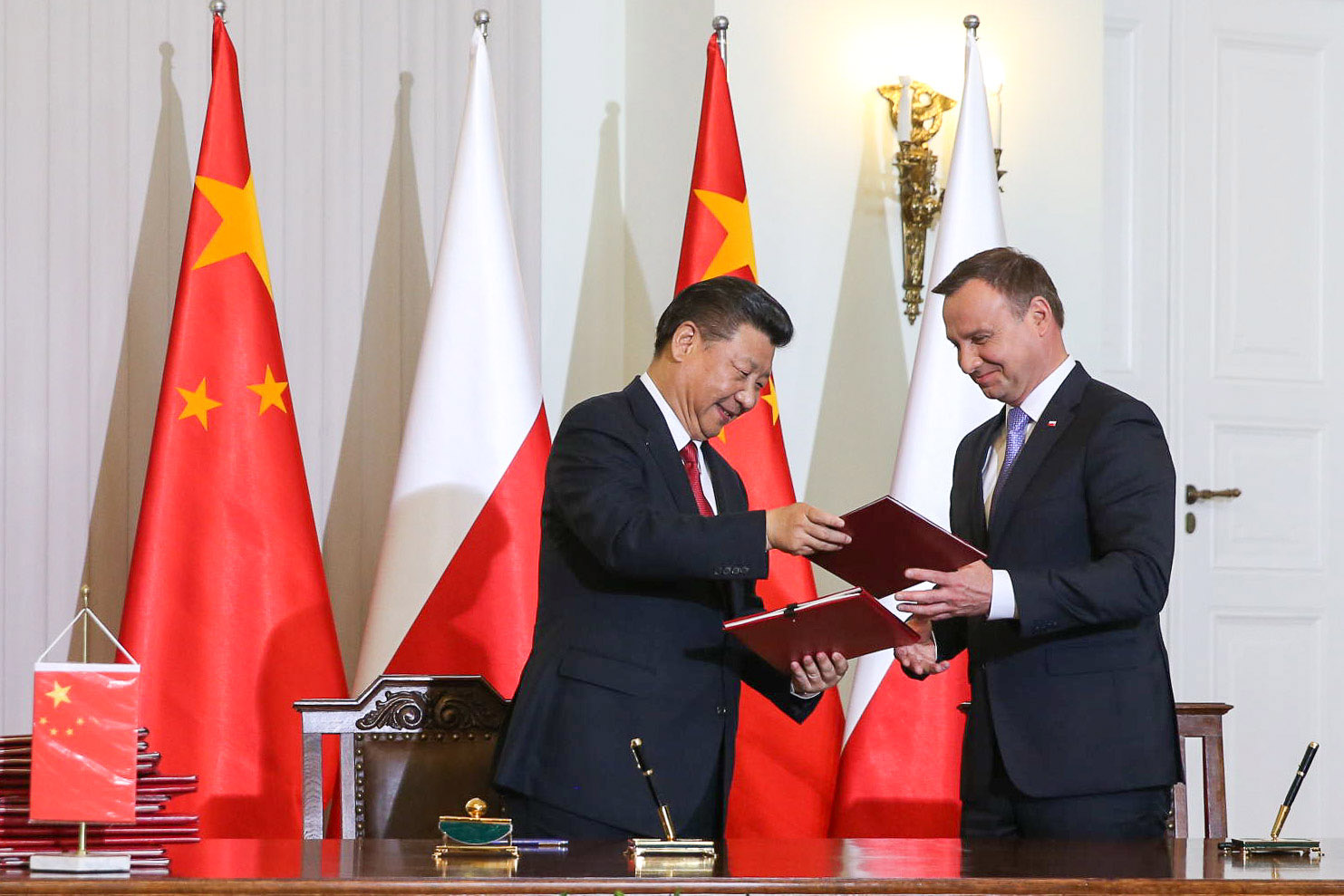

In truth, the opposition to the CAI was yet another signal of growing distrust between Poland and China. The high expectations which emerged in 2012 after the establishment of the “16+1” initiative and its subsequent series of high-level exchanges, fell off dramatically in the last two years. In 2019, a lack of economic cooperation, Poland`s support for EU`s more assertive China policy, as well as the alignment with the US perception of China-related security threats (exemplified by the espionage case involving a Huawei employee) influenced the deterioration of contacts within the “comprehensive strategic partnership”, established in 2016. The ties remained at a reasonably positive level in 2020, but without any signs of a possible breakthrough.

Polish president Andrzej Duda was supposed to attend the “17+1” summit in Beijing scheduled for March 2020, coupled with a bilateral visit to China. However, the plans to organize a bilateral were not successful, due to the disagreements with the Chinese. In the end, the 17+1 summit was canceled as well, due to the pandemic.

The COVID-19 Factor

The COVID-19 pandemic has only worsened the mutual distrust. Poland was one of the many European countries that received medical equipment from China. While China’s “aid” was designed to bolster the image of China in the EU, it mostly backfired due to the questionable quality of the equipment provided and other related controversies.

In the autumn of 2020, when the number of coronavirus cases in Europe rose but reportedly tapered off in China, the Chinese Embassy in Warsaw reiterated the Chinese readiness to support Poland. However, China’s outreach was contradictory to its overall assertive style of diplomacy, and Beijing was thus met only with casual, diplomatic reception. Chinese disinformation activities against the EU (with direct accusations towards Poland of preventing deliveries of Chinese medical equipment to Western countries), or problems with the quality of the medical equipment delivered were the most obvious examples. The worsening perception of China in Poland was also confirmed by the results of a recent survey, where more than half of respondents believe in conspiracies that COVID-19 was created in a Chinese laboratory and intentionally released by the Chinese authorities.

The Importance of 5G

Another important factor influencing Sino-Polish relations is the ongoing development of 5G legislation. These originated from the understanding of Chinese threats shared with American partners, as well as the EU’s toolbox and recommendations from 2020. In September 2020, the Ministry of Digitalization presented a new draft bill of the Act on National Cybersecurity System. It included, among others, regulations on vendor diversification in order to secure the critical infrastructure and 5G development.

One of the procedures put forward by the law involves a risk analysis of hardware and software equipment by representatives of Polish security apparatus with the ability to issue binding decisions on the potential exclusion of Chinese vendors. However, the legal instrument is constructed so as to not directly address the nationality of vendors. This is largely a precaution against eventual lawsuits as such a framework would be incompatible with existing European law.

Changing Perspectives

The ongoing change in perception of China can also be sensed on the political level. In a recent press interview, Polish PM Mateusz Morawiecki said that “[as] China is growing stronger, we are dealing with an enormous challenge for the West”. Concerns about how China used the pandemic for propaganda purposes were also shared by senior members of the Polish ruling party. The shared threat perception of China was also mirrored in Polish policy in the EU or NATO. Former Polish MFA Anna Fotyga (and EP MEP) was a member of “the reflection group” responsible for preparing a report “NATO 2030. United for a New Era”, published in December 2020. It emphasized the threat caused by growing China to NATO and stressed the need for cooperation. Although Ms. Fotyga served as an independent expert, the findings of the report also to a great extent reflect Poland’s understanding of its China’s policy.

In 2021 both the Belt and Road Initiative and “17+1” will most probably lose significance in Chinese foreign policy, due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the importance of Central Europe and Poland in Chinese policy will be reduced.

Neither Poland nor China are interested in a sudden breakdown of their relations. However, political differences, economic imbalances and lack of mutual interests are preventing them (but mostly Poland) from enhancing their cooperation.

China’s determination in the rivalry with the US will probably only grow stronger. Therefore, it is likely that it will also be a harbinger for a more assertive approach in relations with Poland signaled by the accusations of Poland being an accomplice of the US in Chinese social media. However, the possibility of China trying to drive a wedge between Warsaw, Brussels and Washington cannot be entirely excluded. It can use the completion of CAI’s negotiations to present itself as focused on keeping the terms of the agreement and promises on market opening, ILO conventions etc. At the same time, it will try to play up the CAI in the context of Poland’s membership in the EU. In this context, Beijing will maintain interest in keeping up the strategic partnership with Brussels while Poland acts as the brakeman of EU-China rejuvenation.

In the end, the fact that China has not signaled any kind of retribution for Poland’s action on 5G and CAI only confirms Poland’s waning importance in the eyes of the leaders in Beijing. Therefore, Poland’s impact on the EU and US policy (as well as transatlantic cooperation) will remain – from China’s vantage point – seriously limited.

Written by

Marcin Przychodniak

Molos123Marcin Przychodniak is an Analyst at Asia-Pacific program at the Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM), focusing on Chinese politics and a former diplomat in Beijing.