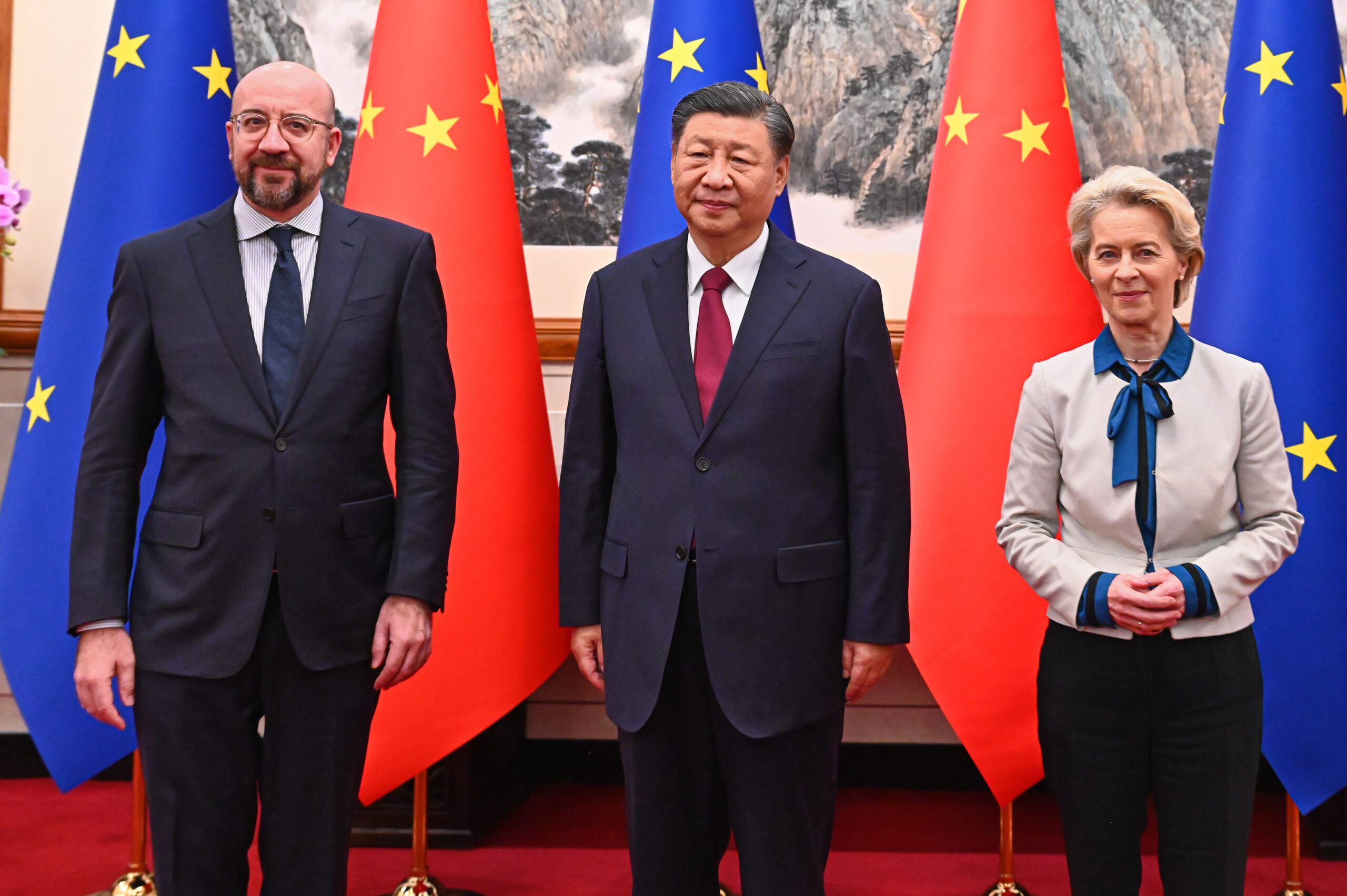

Chinese and European leaders have met once again at the highest levels. Yet, this time was special as it marked the 50th anniversary of EU-China diplomatic relations. It was expected to reaffirm the importance of their relationship in turbulent times of war, economic troubles, and the mounting impacts of global warming. If this was the lowest bar of expectations, it has been met. But the world needs more than that.

It needs practical EU-China cooperation – especially on climate change. This seems to be the “safe haven” many are pinning their hopes on: managing differences in trade and geopolitics, while pursuing selective cooperation on global commons, with climate change as the priority. But can such selective cooperation hold?

The EU has pursued a strategy of linking policy areas to gain leverage, while China rejects isolating climate dialogue from its broader foreign relations. Against this backdrop, it is important to ask: how have rising tensions in the EU-China relationship impacted cooperation – and what does the recent summit tell us about the future of their climate engagement?

Eroding Trust in Difficult Times

European expectations were rock-bottom heading into the summit. Years of growing frustration have shaped a long list of complaints: Chinese subsidies distorting the EU market, limited market access for European firms in China, Chinese export controls on rare earths critical for European green technologies and defense industries, cyberattacks on state agencies, human rights violations, and China’s (non-)actions that enable Russia’s war in Ukraine.

The last point is a particular thorn in the EU’s side. As former Commission President José Manuel Barroso put it: “Although presenting their position always as neutral […] [China] is clearly with Russia.” Saying one thing and doing another is seen by the EU as breaking the trust that underpinned the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership from 2003 and the EU-China 2020 Strategic Agenda for Cooperation from 2013.

Some argue that cooperation with China “does not require deep trust.” Others say trust is a prerequisite for cooperation. Trust is elusive – hard to win, and even harder to regain once lost. Political theorist Russell Hardin once wrote, referring to the basic interest in maintaining a relationship: “I trust you because I think it is in your interest to take my interest […] seriously. […] That is, you encapsulate my interests in your own.”

Both China and the EU have repeatedly emphasized that their relationship is too important to fail. This was echoed by European Council President António Costa at the 2025 summit: “The EU and China have a shared interest in pursuing a constructive, stable, balanced, and mutually beneficial relationship.” So far, so good. But the practical implementation is the hard part. Here, the EU’s principled pragmatism meets China’s holistic pragmatism – that is, European practical considerations coupled with values and principles as red lines meet Chinese “pragmatic firmness and strategic flexibility as […] guiding principles for resolving practical issues.” This prompts the following question: has climate change become the one area where practical considerations outweigh trade and political tensions?

Climate Cooperation vs. Trade Frictions

Trade tensions have escalated in recent years. In 2021, Brussels and Beijing clashed over human rights, imposed sanctions on politicians and researchers, and eventually shelved the planned Comprehensive Investment Agreement. From 2023 onward, the EU’s de-risking agenda sparked a tit-for-tat tariff battle. The EU launched anti-subsidy probes into Chinese EVs and wind turbines, leading to tariffs of 35.3 percent on Chinese-produced EVs in October 2024, on top of the standard 10 percent import duty. China retaliated with anti-dumping investigations into European pork, dairy, and brandy, hitting France and Spain particularly hard.

Yet climate dialogues have continued. In September 2020, both sides established a High-Level Environment and Climate Dialogue (HECD). Despite their trade frictions, the EU and China have held meetings every year: September 2021, July 2022, July 2023, June 2024, and for the sixth time in July 2025. They have also maintained the ministerial-level Environmental Policy Dialogue, holding it for the tenth time in June 2025. The EU-China Energy Dialogue has also not been abandoned – neither in 2023 amid the EU’s anti-subsidy probe into Chinese EVs, nor in 2025 while the issue persisted. Moreover, the High-Level Dialogue on Circular Economy was held for the first time in September 2023, producing a cooperation roadmap for 2024 onward, followed by a second meeting alongside the HECD this year.

While the EU continues to highlight its longstanding trade deficit with China (€305.8 billion in 2024), the election of Donald Trump prompted Commission President Ursula von der Leyen to call for an expansion of trade and investment ties with China. Early 2025 was a mix of rapprochement and tactical leverage-building: China exempted some major cognac producers from tariffs and lifted sanctions imposed on European institutions in 2021. But when the EU blocked Chinese medical device suppliers from public tenders worth more than €5 million, arguing this was proportionate to China’s own barriers, Beijing retaliated by excluding EU firms from Chinese public procurement contracts above 45 million RMB (about €5 million).

In this context, the lead up to the EU-China Summit was marked by uncertainty over its date and location, with the fact that it was shortened from two days to one reflecting the tense atmosphere. Compared to the comprehensive outcome of the EU-Japan Summit held just days prior, the Joint Press Statement on Climate from the EU-China Summit underscored the limited common ground. Nevertheless, the two sides focused on “strengthening results-oriented actions,” including bilateral cooperation in the energy transition and green and low-carbon technologies to “drive their respective green and low-carbon transition processes together.” The success of this climate partnership will depend on how Beijing and Brussels manage their disagreements over solar panels, wind turbines, and electric vehicles.

A Closer Look at Solar

Photovoltaics (PVs) had already been at the center of discontent in 2013, when the European Commission imposed provisional anti-dumping duties on Chinese PVs, prompting Beijing to launch a retaliatory anti-dumping and anti-subsidy probe into EU wine. The latter was settled in 2014 after a business-to-business dialogue between both wine industries reduced tensions. The solar panel dispute was brought to an end in 2017 with an agreement on a minimum price and export limits. However, the resulting drop in Chinese solar panel imports did not lead to a higher market share for the European industry; rather an increase of imports from other countries, primarily from South Asia.

By 2023, China’s share of EU solar panel imports had risen to 98 percent. With the EU’s plan to increase solar power capacity to 700 GW by 2030, it faces a dilemma: how to achieve its renewable energy goals cost-effectively while securing strategic autonomy. The Commission needs to balance the interests of European PV manufacturers, who want trade measures to help them compete with Chinese companies, against those of solar panel importers and installers, who would lose access to affordable solar panel components if such trade measures were applied. Economic arguments for boosting EU manufacturing – such as green growth and job creation have been dismissed as unrealistic, leaving strategic autonomy as the main rationale. This is where trust comes back into play.

Is Rebuilding Trust Possible?

For the EU, China’s trustworthiness is in doubt because it does not share the same values and principles regarding human rights, openness in decision-making, and adherence to rules and agreements. At its core, this comes down to trust in what the other side will – and will not – do. The EU’s belief that China encapsulates European interests within its own, as promoted in the oft-repeated “win-win” rhetoric, is limited by a ranking of interests with China’s at the top. This applies vice versa as well.

The Brexit negotiations offer a useful parallel: once trust was broken by the UK, the EU adjusted its negotiation strategy and adopted more oversight, monitoring, and retaliatory mechanisms to reduce uncertainty. In the EU-China relationship, the EU’s adoption and use of instruments such as the Foreign Subsidies Regulation serve a similar function. But as the Brexit case also showed, “trust dies hard” because it is tied to specific issues and contexts. Breaches of trust may not sink an entire relationship, but they will change the quality of cooperation.

In the EU-China case, climate and trade dialogues are valuable, but tangible and verifiable implementation of small practical agreements could go further in building a trust framework for deeper cooperation. “Shelving differences” cannot be the long-term strategy. An indication of good will was the summit agreement to establish an “upgraded version” of the China-EU export control dialogue mechanism and China’s willingness to import more EU products compatible with China’s market demands. At the same time, Beijing rejected the “Chinese overcapacity narrative” and refused to let the Russia-Ukraine war become part of the agenda.

Instead of linking issues for leverage, both sides still seem intent on keeping climate cooperation and trade frictions separate to shield at least one area of default good will. The enduring sticking point will be Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Here, the EU needs to be honest with itself about its role and options, and China will need to have an equally honest debate about whether an “unlimited partnership” with Russia truly serves its best interests.

Written by

Kim Vender

Dr Kim Vender is an Affiliated Researcher at the Centre for EU-Asia Connectivity (CEAC) at Ruhr University Bochum, Germany. Her research interests encompass the complexities of climate change and biodiversity governance, climate finance (especially Loss and Damage), development cooperation, the concept of international leadership, and China’s engagement with the EU and Latin America. Kim holds a PhD in Politics and International Relations from the University of Edinburgh, an MA in East Asian Politics from Ruhr University Bochum, and a BA in China Studies from the Free University of Berlin. She recently published her book "China and Climate Leadership: A Role Theory Analysis" with Routledge.