Over the last six months, China’s much-touted Global Security Initiative has quickly gained prominence within China’s broader diplomatic outreach. Yet, it is uncertain whether China can implement the GSI successfully.

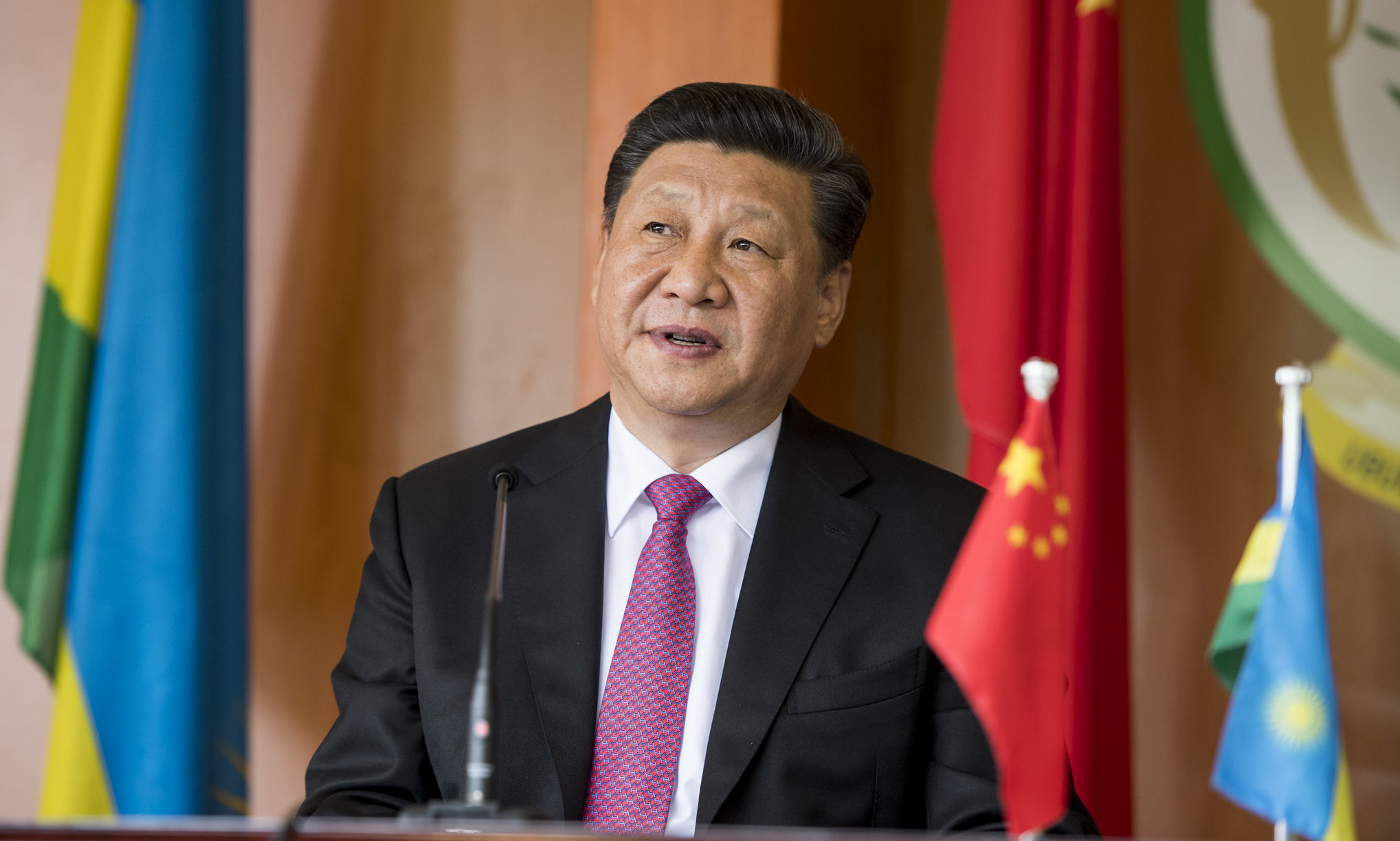

Announced by Xi only in April this year, the Global Security Initiative (GSI) is adding to an alphabet soup of existing policy acronyms such as the Global Development Initiative (GDI) and, of course, the well-known Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Since its inception, the GSI has received sustained attention among China scholars. This is not particularly surprising, given the timing of the initiative shortly after the start of Russia’s war in Ukraine, a defining event of the post-Cold War era that may alter global security governance for decades to come. Suspicion across Western capitals of a potential Sino-Russian military alliance in the wake of the war certainly contributed to additional speculation about the underlying motifs of the GSI. While a fully-fledged alliance did not materialize, and Beijing has so far not provided large-scale military aid to Moscow, discussions on the GSI have continued.

When discussing the Chinese initiative, it is crucial to ground our understanding in a realistic assessment of what the GSI is actually able to do, moving from an assessment of Beijing’s intentions to critically evaluating China’s capabilities of putting the GSI into action. Once contextualized in a realistic account of China’s role as a global security actor, the GSI in its current form becomes more of a rhetorical – and propagandistic – concept to promote Sinocentric visions for global security governance rather than a solid blueprint for implementing such a China-led order.

Rhetorical Ambiguity

While the GSI has been couched in ambitious rhetoric, it has remained thin on concrete details. As Chris Cash notes in a recent explainer, the GSI is based on six central commitments, including an emphasis on sovereignty, the UN charter, and “indivisible security.” The latter is particularly noteworthy.

First set out in the 1975 Helsinki Accords, which set ground rules for European security in an age of great power competition, indivisible security means that the security of any particular country is inseparable from other countries’ security in the region. One country’s quest for security should consequently not come at the detriment of another’s. Ironically, the concept has been invoked by Vladimir Putin to criticize the expansion of NATO, an assessment that Beijing has repeatedly supported since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Citing indivisible security, Beijing has attempted to harmonize its longstanding rhetorical commitment to sovereignty and non-interference with the desire to maintain its close relationship with Moscow.

Light on concrete material commitments, the GSI has thus far functioned as a catch-all phrase to criticize the existing US-led global security order while advancing China’s own understanding of global security governance. The recent Party Congress report, for instance, cites the GSI under the chapter “Promoting World Peace and Development and Building a Human Community with a Shared Future,” framing the initiative as a global public good China is willing to offer in times of instability and change. Semi-authoritative commentaries from China’s most important military newspaper, Jiefangjun Bao, echo official policy speeches in describing the GSI in the context of China’s contribution to global public goods, reflecting China’s willingness to build a “universally secure world” (普遍安全的世界).

The GSI has also found its way into a wide array of foreign policy and diplomatic activities across Africa and the Middle East. The GSI has thus relatively quickly gained prominence in China’s diplomatic rhetoric, reflecting how many organizations and institutions of the party-state have been mobilized to propagate Xi Jinping’s latest policy slogan.

Practical Challenges

However, despite this initial enthusiasm, the GSI will encounter sizable challenges in practice. First, regardless of China’s intentions, it is questionable whether the GSI will be accompanied with sufficient regulatory tools to put Xi’s lofty policy goals into meaningful action. The GSI nominally focuses on both non-traditional and traditional security issues. If China were to securitize its existing relationship with foreign partners, it would have to account for a whole lot of different security-related activities of a diverse set of Chinese actors. Private Chinese security companies patrolling BRI projects, state-owned defense companies integrated into the global arms market, China’s armed forces and their auxiliary branches – the People’s Liberation Army, the People’s Armed Police and the Maritime Militia, and a host of diplomatic actors under the Ministries of Foreign Affairs, Public Security and Defense – all these actors make up China’s global security footprint in different ways and would have to be coordinated for the GSI to amount to a homogeneous, Sino-centric security order.

A consequence of the “Go Out” policy, which oriented China’s economy and party-state towards engaging the global economy over the past two decades, has been the proliferation of Chinese commercial ventures overseas, often amidst a rather weak regulatory framework to prevent and mitigate associated negative externalities. While China has centralized to a considerable degree under Xi Jinping, some of these dynamics persist even in the realm of security governance.

The GSI would need an incredibly powerful policy framework to coordinate the different and sometimes conflicting objectives and vested interests of different groups of Chinese actors spanning traditional and non-traditional security operations abroad. It would be a hard sell for China to promote the GSI in any meaningful way across Southeast Asia while simultaneously engaging in grey zone operations through the maritime militia in the South China Sea. Moreover, the GSI would have to go beyond security to include commercial actors.

Environmental risk mitigation would surely be a welcomed element of the GSI. Yet, how will Beijing reconcile such novel ambitions with the reality of China’s globally operating fishing fleets that have contributed to the depletion of maritime commons from Africa all the way to Latin America? Similarly, how will the GSI address illegal Chinese mining activities in countries such as Ghana, driven by a complex local political economy that destabilizes and threatens the livelihood of local communities?

This is not an issue of cherry-picking evidence to discredit the potential of the GSI, but rather about showing the gargantuan challenge of any meaningful implementation of the initiative. In the absence of dealing with these diverse negative externalities, the GSI will be little more than a rhetorical framework to advance an idealistic vision of global security, while offering little concrete to alleviate the problems at hand and emancipate local communities.

Second and because of the above, we have to take into account the role and agency of local governments and civil society groups across the developing world. Despite the GSI’s relevance to Sino-Russian relations, it will have the most currency across the Global South, where China most readily finds an audience for its alternative ideas for global order. While Xi has begun to articulate a more assertive vision of how global security governance ought to develop, the success and impact of his initiative will ultimately depend on Chinese partners’ willingness to cooperate under the framework of the GSI. In fact, far from being solely driven by Chinese interests, governments across the developing world have long requested Beijing to become more involved in solving regional and local security issues. Accounting for their agency is critical to understand the long-term future of the initiative.

To give one example, China has promoted the GSI especially vividly in the wider Horn of Africa. Xue Bing, China’s Special Envoy to the Horn of Africa, has tied the GSI to China’s recent efforts to promote peace and stability in the region, framing China as a constructive external actor. Yet, Xue has so far not been very successful at solving some of the long-standing conflicts in the region. This has mainly been due to China’s long-standing relationships with regional governments and its unwillingness to alienate any one player across the region at the expense of another. The Chinese Special Envoy has consequently shied away from tackling some of the most controversial regional security issues head-on, including the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) or the conflict in northern Ethiopia.

While China’s more pro-active approach to crisis diplomacy is in principle to be welcomed, Beijing rarely sets the agenda in these scenarios and prefers to leave the actual negotiations to regional parties. Although the recent agreement to cease hostilities between the Ethiopian government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) is promising, it was the African Union and regional governments – and not China – that led these negotiation efforts. An understanding of the GSI as a one-size-fits-all policy tool is thus premature.

Overall, it certainly remains important to watch the evolution of the GSI and its relationship to China’s broader ambitions to reform global governance in the years to come. When analyzing China’s intentions, however, it will be critical to keep in mind the very real constraints it is likely to encounter in practice.

Written by

Lukas Fiala

LukasdkFialaLukas Fiala is Project Coordinator at China Foresight, LSE IDEAS, and a PhD International Relations candidate at LSE.